Published: February 28, 2019

Updated: January 30, 2021

Updated: January 30, 2021

Introduction

Montréal-Mirabel International Airport was once planned to be one of the largest airports in the world. Envisaged as a major hub connecting Europe with North America, it would have featured six runways and six passenger terminals in its final layout.

However, for a variety of reasons, this grand vision never materialized. The airport never handled more than 3 million passengers annually, and in 2004, it was closed for passenger traffic. Mirabel became known as the biggest airport planning blunder in the world.

Nevertheless, this does not do justice to the fact that the airport itself was a very well-planned facility. The passenger terminal, for example, was very advanced for its time and considered one of the world's best. In recent years, Mirabel has found some "redemption" as a very successful aviation production cluster.

In this multi-part article we will present the fascinating history of Mirabel and provide some new insights into the story. In this fully updated first part, we will focus on the Master Plan and the rationale behind the new airport.

However, for a variety of reasons, this grand vision never materialized. The airport never handled more than 3 million passengers annually, and in 2004, it was closed for passenger traffic. Mirabel became known as the biggest airport planning blunder in the world.

Nevertheless, this does not do justice to the fact that the airport itself was a very well-planned facility. The passenger terminal, for example, was very advanced for its time and considered one of the world's best. In recent years, Mirabel has found some "redemption" as a very successful aviation production cluster.

In this multi-part article we will present the fascinating history of Mirabel and provide some new insights into the story. In this fully updated first part, we will focus on the Master Plan and the rationale behind the new airport.

Big plans for an ambitious city

THE BOOMING 1960s

In the 1960s, Montréal was Canada's largest city and the third-largest city in North America after New York and Chicago. It was also Canada's commercial and cultural center. During that era, the city experienced an economic boom and Montréal's city leaders, led at the time by Mayor Jean Drapeau, were thinking big in terms of asserting the city's status as a prestigious, forward-looking metropolis.

During that decade several of the city's tallest skyscrapers were constructed as well as a city-wide network of expressways and subway lines. The enormous success of the Expo 67 World's Fair held in Montréal was one of that era's crowning achievements. In 1970, Montréal was awarded the 21st Summer Olympics, held in 1976. The city seemed invincible as the epicenter of business and culture for the province of Québec and all of Canada.

In the 1960s, Montréal was Canada's largest city and the third-largest city in North America after New York and Chicago. It was also Canada's commercial and cultural center. During that era, the city experienced an economic boom and Montréal's city leaders, led at the time by Mayor Jean Drapeau, were thinking big in terms of asserting the city's status as a prestigious, forward-looking metropolis.

During that decade several of the city's tallest skyscrapers were constructed as well as a city-wide network of expressways and subway lines. The enormous success of the Expo 67 World's Fair held in Montréal was one of that era's crowning achievements. In 1970, Montréal was awarded the 21st Summer Olympics, held in 1976. The city seemed invincible as the epicenter of business and culture for the province of Québec and all of Canada.

THE CASE FOR A NEW AIRPORT

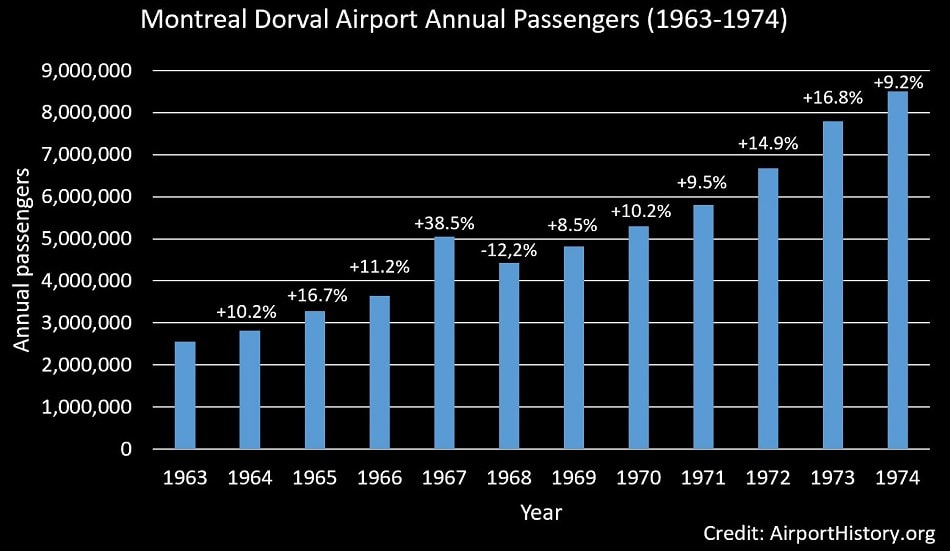

Due to the boom, passenger traffic at the city's international airport at Dorval was growing at double-digit rates. In 1965, Dorval handled 3.3 million passengers, 16.7% more than the previous year. Five years prior, the airport had been expanded with a brand-new terminal complex and a third runway. However, it was clear that planners already needed to consider the next round of expansion.

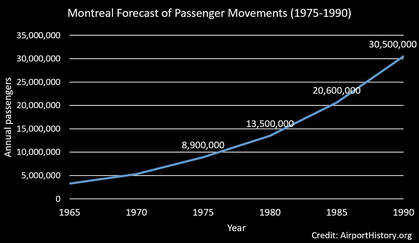

Over 1967-68, Canada's Department of Transport carried out a number of studies of the city's air transport requirements over the next 25 to 30 years. According to one study, airline passenger traffic would double every eight years. According to this scenario, annual passenger movements would reach 20.6 million by 1985 and 30.5 million by 1990. It was also forecast that air cargo would double every three or four years and general aviation would double every ten years.

Another study revealed that Dorval Airport would reach a saturation point by 1975, and that even if it was expanded, it would reach its maximum capacity by 1985. Beyond that, an additional runway would need to be built, which would require the acquisition of very expensive land.

Due to the boom, passenger traffic at the city's international airport at Dorval was growing at double-digit rates. In 1965, Dorval handled 3.3 million passengers, 16.7% more than the previous year. Five years prior, the airport had been expanded with a brand-new terminal complex and a third runway. However, it was clear that planners already needed to consider the next round of expansion.

Over 1967-68, Canada's Department of Transport carried out a number of studies of the city's air transport requirements over the next 25 to 30 years. According to one study, airline passenger traffic would double every eight years. According to this scenario, annual passenger movements would reach 20.6 million by 1985 and 30.5 million by 1990. It was also forecast that air cargo would double every three or four years and general aviation would double every ten years.

Another study revealed that Dorval Airport would reach a saturation point by 1975, and that even if it was expanded, it would reach its maximum capacity by 1985. Beyond that, an additional runway would need to be built, which would require the acquisition of very expensive land.

NOISE CONCERNS

Even more critical would be the noise problem that would come with the increased air traffic. In the late 1960s, people living near the airport were already protesting against existing noise levels and demanding action from the federal government.

Restrictions were imposed on night flights at Dorval. This alleviated problems somewhat, but with the growth of traffic and the large-scale introduction of wide-body and supersonic jetliners on the horizon, a long-term solution was needed.

THE DECISION

After weighing all the factors involved, the government decided in 1968 that the future aviation needs of the Montréal area could only be met by the construction of a new international airport, one which would be suitable for the new generation of aircraft and the largely unknown demands of the 21st century.

Even more critical would be the noise problem that would come with the increased air traffic. In the late 1960s, people living near the airport were already protesting against existing noise levels and demanding action from the federal government.

Restrictions were imposed on night flights at Dorval. This alleviated problems somewhat, but with the growth of traffic and the large-scale introduction of wide-body and supersonic jetliners on the horizon, a long-term solution was needed.

THE DECISION

After weighing all the factors involved, the government decided in 1968 that the future aviation needs of the Montréal area could only be met by the construction of a new international airport, one which would be suitable for the new generation of aircraft and the largely unknown demands of the 21st century.

Location, location, location

THE IDEAL LOCATION

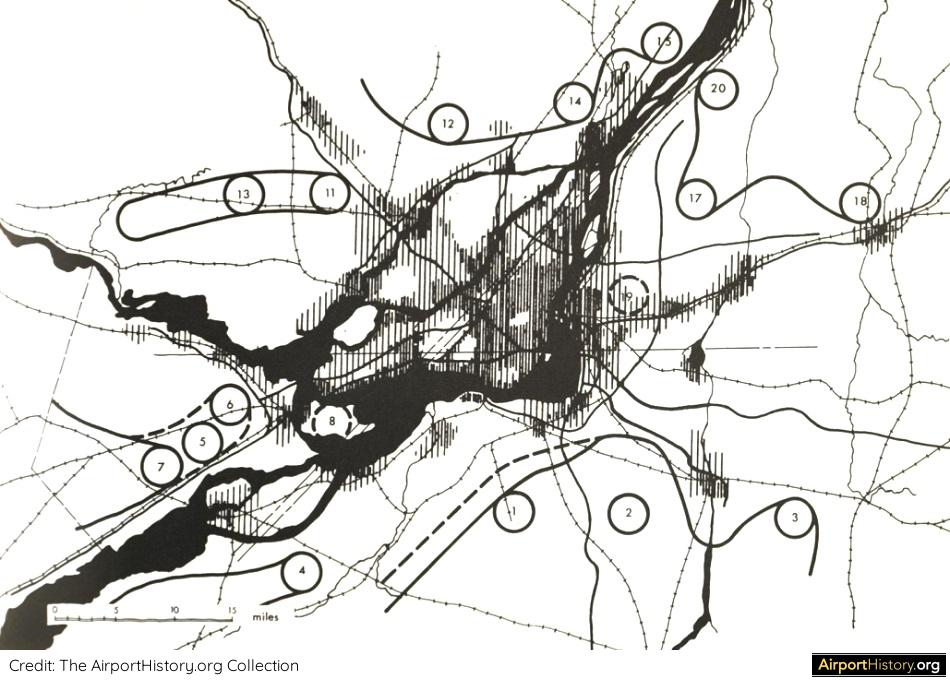

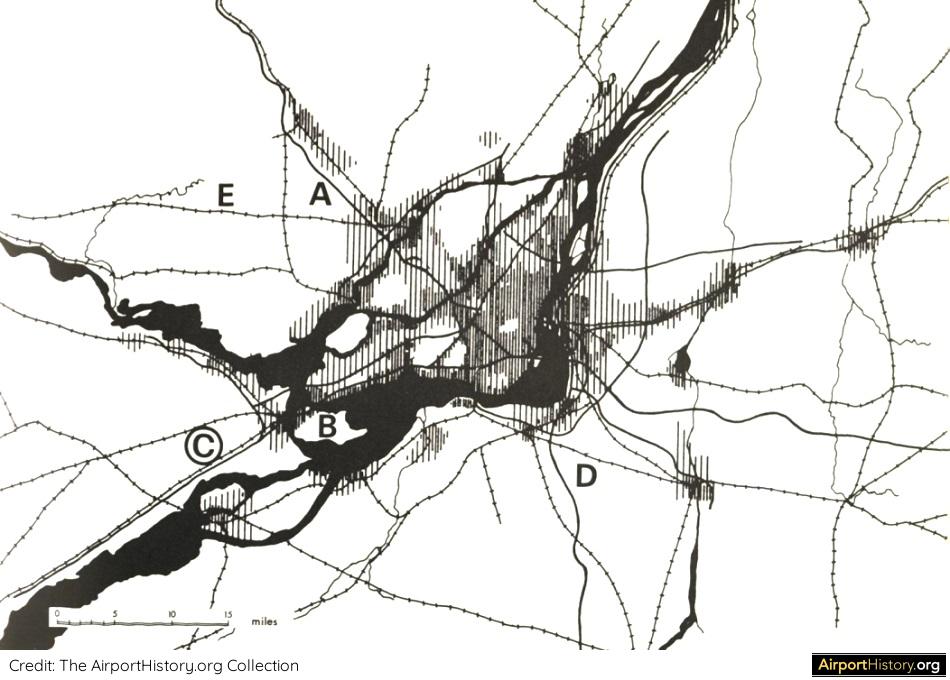

The Canadian Department of Transport studied 20 possible sites for the new airport, which was narrowed down to five. The Montreal International Airport Study came to the conclusion that the airport should be located in Vaudreuil-Dorion, 30 miles (45 km) to the south-west of downtown Montréal, just west of the Island of Montréal.

The site was traversed by existing expressways and railways connecting Montréal to Ottawa and Toronto; thus minimizing necessary investments in landside surface transport connections. In addition, due to its location, it could serve as the gateway to both Ottawa and Montréal. Lastly, due to its proximity to the existing airport of Dorval, airport workers would not have to move in order to keep their jobs.

The Canadian Department of Transport studied 20 possible sites for the new airport, which was narrowed down to five. The Montreal International Airport Study came to the conclusion that the airport should be located in Vaudreuil-Dorion, 30 miles (45 km) to the south-west of downtown Montréal, just west of the Island of Montréal.

The site was traversed by existing expressways and railways connecting Montréal to Ottawa and Toronto; thus minimizing necessary investments in landside surface transport connections. In addition, due to its location, it could serve as the gateway to both Ottawa and Montréal. Lastly, due to its proximity to the existing airport of Dorval, airport workers would not have to move in order to keep their jobs.

GALLERY: POTENTIAL LOCATIONS (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

Enjoying this article?

Sign up to our e-mail newsletter to know when new content goes online!

A COMPROMISE: MIRABEL

However, the provincial Québec government found this location to be too close to the Ontario border. It feared that airport workers might move to lower-taxed Ontario. Québec nationalist sentiments reportedly also played a role.

Instead, it preferred that the new airport be situated near Drummondville, 70 miles (110 km) to the east of Montréal. Drummondville is located halfway between both Montréal and the provincial capital Québec City, thus allowing the airport to serve as an international gateway to both cities.

However, the provincial Québec government found this location to be too close to the Ontario border. It feared that airport workers might move to lower-taxed Ontario. Québec nationalist sentiments reportedly also played a role.

Instead, it preferred that the new airport be situated near Drummondville, 70 miles (110 km) to the east of Montréal. Drummondville is located halfway between both Montréal and the provincial capital Québec City, thus allowing the airport to serve as an international gateway to both cities.

|

In March of 1969, the federal and provincial governments reached a compromise to locate the new airport at "Location A", near the village of Sainte-Scholastique, 30 miles (45 km) to the north-west of the city center of Montréal and within view of the Laurentian mountains.

The airport would be named Mirabel, after a farm owned by one of the original 19th century settlers. During the First World War there was a Grand Trunk Railway station called Mirabel in the area. |

Mirabel did not score badly in the report. However, it had one major issue: a lack of surface transport connections. Only one major road, Route 15, ran through the area. The report strongly recommended that a second expressway be built in time for the opening of Mirabel, and a third one by 1985. Also, an airport rail connection to downtown would have to be built as soon as possible.

The largest airport in the world

THE VISION

Montréal was located right on the hinge-point of the world's two fastest growing aviation markets: the US domestic and transatlantic market. Montréal was the first major city on the way from Europe to the US east coast and midwest. Thus, Mirabel was poised to develop into the primary hub connecting European capitals with cities in Canada and the US.

Due to its location, Montréal also was a convenient transit point for the early jets, which had limited range. European carriers such as KLM and Air France used Montréal as a stopover point on their way to Chicago, New York or Houston. Lastly, bilateral treaties of the time dictated that most European flag carriers wishing to fly to Canada could only serve Montréal.

Planners also envisaged a big future for cargo. At the time, Montréal was an up-and-coming freight center. It was hoped that a brand-new airport offering state-of-the-art facilities could siphon off large amounts of cargo traffic from overcrowded nearby centers like Boston and New York.

Montréal was located right on the hinge-point of the world's two fastest growing aviation markets: the US domestic and transatlantic market. Montréal was the first major city on the way from Europe to the US east coast and midwest. Thus, Mirabel was poised to develop into the primary hub connecting European capitals with cities in Canada and the US.

Due to its location, Montréal also was a convenient transit point for the early jets, which had limited range. European carriers such as KLM and Air France used Montréal as a stopover point on their way to Chicago, New York or Houston. Lastly, bilateral treaties of the time dictated that most European flag carriers wishing to fly to Canada could only serve Montréal.

Planners also envisaged a big future for cargo. At the time, Montréal was an up-and-coming freight center. It was hoped that a brand-new airport offering state-of-the-art facilities could siphon off large amounts of cargo traffic from overcrowded nearby centers like Boston and New York.

THE DESIGN CHALLENGE

Considering the expected growth, planners were looking for an airport layout with near infinite capacity and where they could incorporate the latest design concepts. At the time, the trend in airport construction was to minimize walking distances and to drop off passengers as close to the door of the aircraft as possible.

The new generation of wide-body aircraft had to be brought close to the terminal so as to efficiently load passengers and cargo, but also needed plenty of space to maneuver because of their size. Also, enough land would need to be protected for future development and to prevent noise concerns.

INSPIRATION FROM TEXAS

For inspiration they looked at the giant new jetport proposed at the time for the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas.

That airport incorporated the concept of a center spine road, which brings a main artery for surface transport right down the middle of the airport. Rather than one large passenger terminal, a number of decentralized terminals were arranged around the spine road. Each terminal was to be operated by a major airline or a number of smaller ones.

Considering the expected growth, planners were looking for an airport layout with near infinite capacity and where they could incorporate the latest design concepts. At the time, the trend in airport construction was to minimize walking distances and to drop off passengers as close to the door of the aircraft as possible.

The new generation of wide-body aircraft had to be brought close to the terminal so as to efficiently load passengers and cargo, but also needed plenty of space to maneuver because of their size. Also, enough land would need to be protected for future development and to prevent noise concerns.

INSPIRATION FROM TEXAS

For inspiration they looked at the giant new jetport proposed at the time for the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas.

That airport incorporated the concept of a center spine road, which brings a main artery for surface transport right down the middle of the airport. Rather than one large passenger terminal, a number of decentralized terminals were arranged around the spine road. Each terminal was to be operated by a major airline or a number of smaller ones.

THE MIRABEL MASTER PLAN

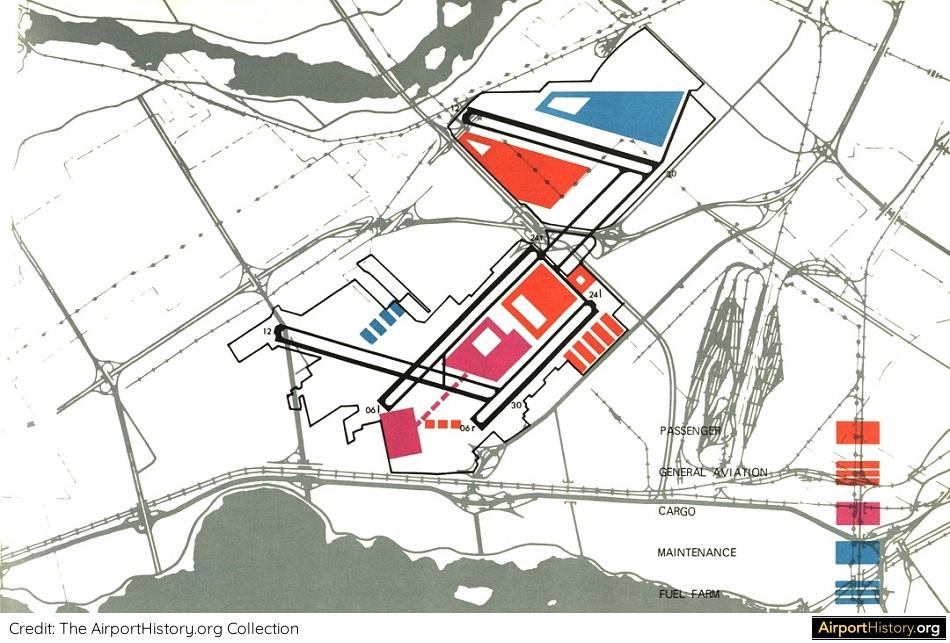

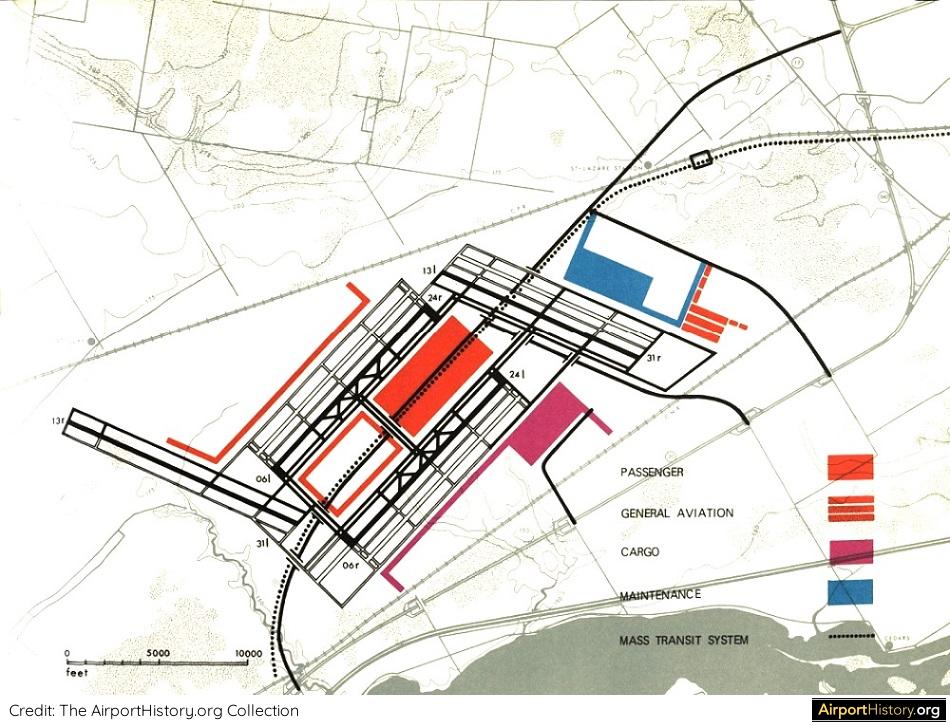

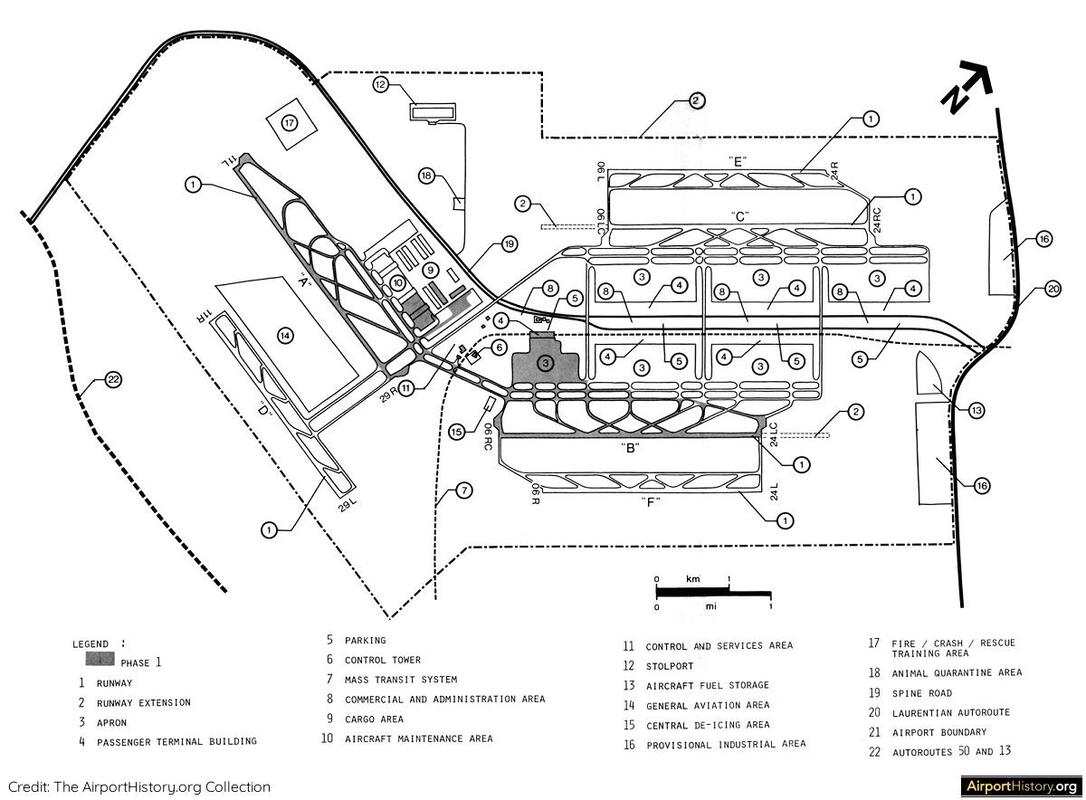

The Mirabel Master Plan envisaged an airport of 17,000 acres (6,879 hectares), slightly smaller than the size of Dallas/Fort Worth Airport.

The plan provided for a total of six runways, which were arranged in three pairs of parallel runways: two pairs in the direction of the predominant winds (northeast-southwest) and one pair in the crosswind (east-west) direction. Together these provided a capacity of more than 160 landings and takeoffs per hour, or 630,000 movements per year.

The runway length varied from between 10,000 feet (3,048 meters) up to 15,000 feet (4,572 meters), enabling them to handle the heaviest aircraft of the time and those of the future. However, if necessary, two of the runways could be extended up to 15,000 feet (4,572 meters).

There was also provision for a seventh landing strip of 2,000 feet (610 meters) for so-called STOL (Short Take Off and Landing) aircraft that could transport passengers to nearby cities like Ottawa, Toronto and even downtown Montréal, if the roads would ever become too congested.

The Mirabel Master Plan envisaged an airport of 17,000 acres (6,879 hectares), slightly smaller than the size of Dallas/Fort Worth Airport.

The plan provided for a total of six runways, which were arranged in three pairs of parallel runways: two pairs in the direction of the predominant winds (northeast-southwest) and one pair in the crosswind (east-west) direction. Together these provided a capacity of more than 160 landings and takeoffs per hour, or 630,000 movements per year.

The runway length varied from between 10,000 feet (3,048 meters) up to 15,000 feet (4,572 meters), enabling them to handle the heaviest aircraft of the time and those of the future. However, if necessary, two of the runways could be extended up to 15,000 feet (4,572 meters).

There was also provision for a seventh landing strip of 2,000 feet (610 meters) for so-called STOL (Short Take Off and Landing) aircraft that could transport passengers to nearby cities like Ottawa, Toronto and even downtown Montréal, if the roads would ever become too congested.

The plan provided for the construction of a total of six passenger terminals. Similar to the DFW plan, the terminals would be arranged on both sides of a four-lane spine road, which would bisect the airport.

The spine road could be widened to eight lanes. A reservation was made in the median for an automated people mover (APM) system, connecting the passenger terminals. There were also provisions for extensive cargo and aircraft maintenance areas, a STOL-port, a general aviation area and an airport industrial park.

In the final layout, the total capacity would be a minimum of 60 million passengers, a volume which was expected to be reached by the year 2025. The entire complex was expected to be readied by the year 2000.

The spine road could be widened to eight lanes. A reservation was made in the median for an automated people mover (APM) system, connecting the passenger terminals. There were also provisions for extensive cargo and aircraft maintenance areas, a STOL-port, a general aviation area and an airport industrial park.

In the final layout, the total capacity would be a minimum of 60 million passengers, a volume which was expected to be reached by the year 2025. The entire complex was expected to be readied by the year 2000.

BUFFER ZONE

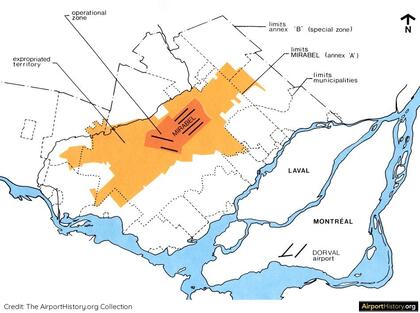

The most controversial part of scheme was the establishment of a huge buffer zone around the airport which was meant to provide a defense against noise and safeguard the airport’s future development. Most of the land would be dedicated to agriculture. Another section would be used to establish an airport industrial zone.

The most controversial part of scheme was the establishment of a huge buffer zone around the airport which was meant to provide a defense against noise and safeguard the airport’s future development. Most of the land would be dedicated to agriculture. Another section would be used to establish an airport industrial zone.

|

In total, an area of 96,000 acres (38,800 hectares), an area size corresponding to more than ¾ of the Island of Montréal, was expropriated to make way for the airport and the buffer zone, affecting 2,700 families.

157 property owners had to move to make way for the initial construction. The others were allowed to remain and given ten-year renewable land leases. The expropriation resulted in making Mirabel the world's largest airport by property area, a record which it retained until 1999, when King Fahd International Airport near Dammam in Saudi Arabia surpassed Mirabel. |

CONNECTIONS TO THE CITY

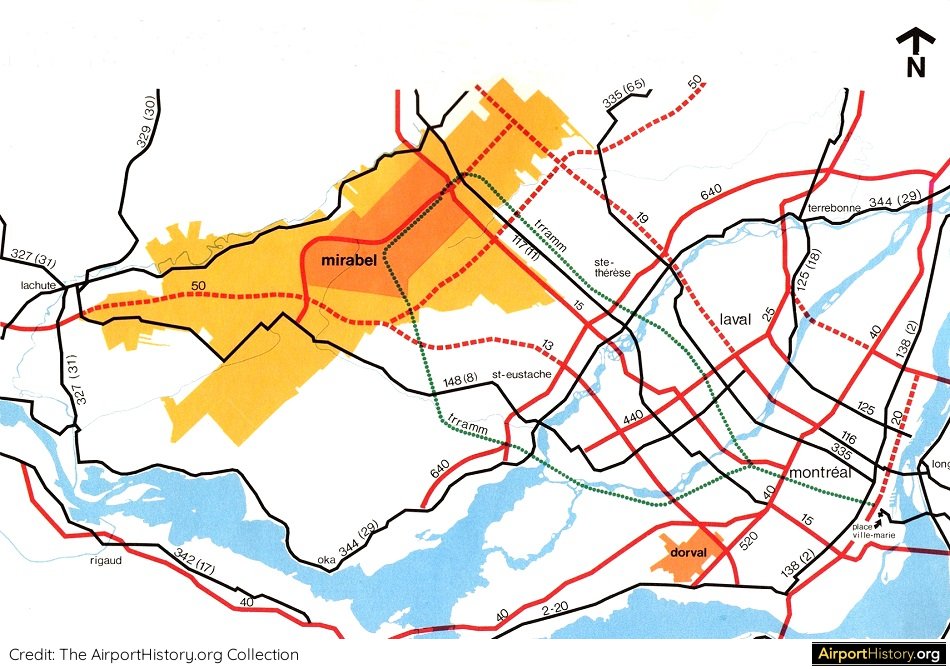

With the airport being located relatively far from Montréal, and only one expressway—Route 15—running through the area, improving surface access was of utmost importance.

Several new expressways were planned: the most important one being the extension of Route 13, which would connect Mirabel to the existing airport at Dorval and Montréal’s prosperous west. Later on, a third expressway connecting Montréal to the airport—Route 19—would be constructed.

Eventually, the new Route 50 would connect the airport to Ottawa, some 90 miles (150 kilometers) away, thereby making Mirabel a viable alternative for inhabitants of Canada's capital.

With the airport being located relatively far from Montréal, and only one expressway—Route 15—running through the area, improving surface access was of utmost importance.

Several new expressways were planned: the most important one being the extension of Route 13, which would connect Mirabel to the existing airport at Dorval and Montréal’s prosperous west. Later on, a third expressway connecting Montréal to the airport—Route 19—would be constructed.

Eventually, the new Route 50 would connect the airport to Ottawa, some 90 miles (150 kilometers) away, thereby making Mirabel a viable alternative for inhabitants of Canada's capital.

GALLERY: SURFACE TRANSPORTATION (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

TRRAMM

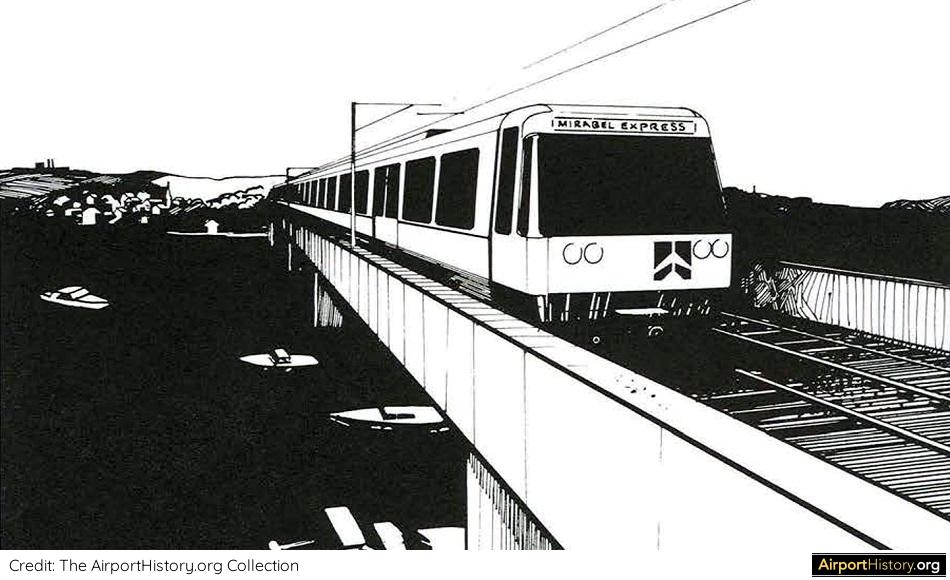

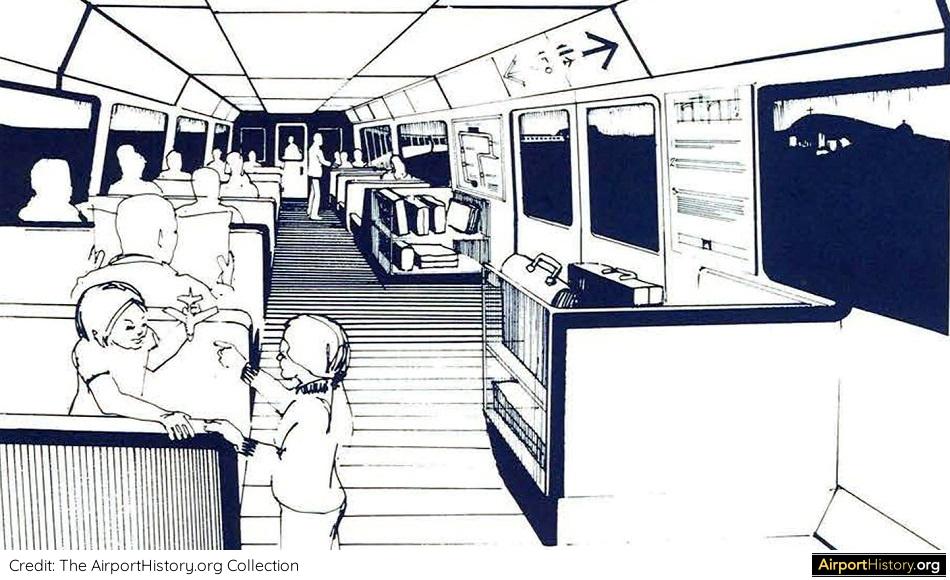

Even with improved highways, during rush hour, the driving time from Montréal to Mirabel would still be an hour. Hence, it was of paramount importance to develop a rail alternative. To address this need, a high-speed light rail from downtown Montréal to Mirabel was planned, called TRRAMM (Transport Rapide Régional Aéroportuaire Montréal-Mirabel).

Trains were able to reach speeds of up to a 100 miles per hour (160 km per hour) and would cover the distance between Montréal and Mirabel in 30 minutes. TRRAMM was to be completed by 1980 and would eventually be expanded to other parts of the Montréal region.

Even with improved highways, during rush hour, the driving time from Montréal to Mirabel would still be an hour. Hence, it was of paramount importance to develop a rail alternative. To address this need, a high-speed light rail from downtown Montréal to Mirabel was planned, called TRRAMM (Transport Rapide Régional Aéroportuaire Montréal-Mirabel).

Trains were able to reach speeds of up to a 100 miles per hour (160 km per hour) and would cover the distance between Montréal and Mirabel in 30 minutes. TRRAMM was to be completed by 1980 and would eventually be expanded to other parts of the Montréal region.

Want to hear what happened next? We will soon upload Part 2, where we will explore the design of the passenger terminal and other facilities!