Published: September 25, 2020

Updated: October 15, 2021

Updated: October 15, 2021

In this fifth installment of our multi-part history on New York John F. Kennedy Airport, we'll see how the airport tried to deal with booming traffic during the 1960s.

Traffic booms at Kennedy

THE NEED FOR EXPANSION

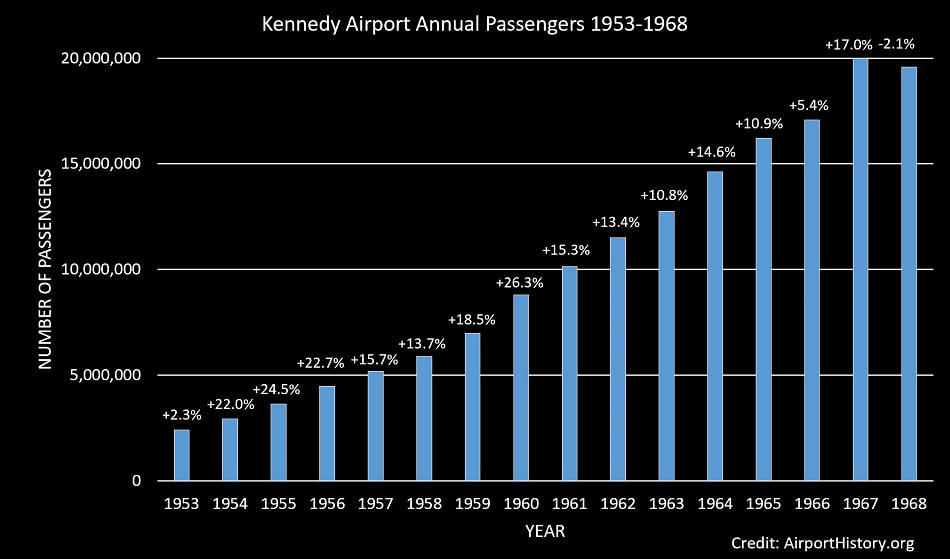

In the 1950s, during the postwar economic expansion millions of Americans took to the skies for the first time. Between 1951 and 1957, passenger traffic at Kennedy doubled. Between 1957 and 1961 traffic doubled again, making the airport the first in the world to break through the 10 million passenger mark.

Movements could still be handled comfortably, as the airport was planned for future growth. However, that changed in the mid-1960s. Between 1961 and 1967, traffic doubled from 10 to 20 million passengers, beating even the most optimistic projections. Traffic was expected to double again by 1975.

In the 1950s, during the postwar economic expansion millions of Americans took to the skies for the first time. Between 1951 and 1957, passenger traffic at Kennedy doubled. Between 1957 and 1961 traffic doubled again, making the airport the first in the world to break through the 10 million passenger mark.

Movements could still be handled comfortably, as the airport was planned for future growth. However, that changed in the mid-1960s. Between 1961 and 1967, traffic doubled from 10 to 20 million passengers, beating even the most optimistic projections. Traffic was expected to double again by 1975.

By the mid-1960s, congestion was becoming a major issue. In 1965, aircraft delays on peak hours had reached 20-30 minutes. It was projected that by 1970 the average aircraft delay would be two hours if the trend continued.

Bottlenecks were everywhere: runways and gates, but also parking lots and roadways. At peak times it could take up to 50 minutes to get from the airport entrance to the IAB! In 1969 the airport became one of five airports to introduce slot controls in response to airside congestion.

Bottlenecks were everywhere: runways and gates, but also parking lots and roadways. At peak times it could take up to 50 minutes to get from the airport entrance to the IAB! In 1969 the airport became one of five airports to introduce slot controls in response to airside congestion.

GALLERY: BUSY SCENES AT KENNEDY (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

There's nothing wrong with Kennedy Airport. There are just too many planes!

- George M. Gary, FAA Eastern regional director, addressing congestion in 1968

Enjoying this article?

Sign up to our e-mail newsletter to know when new content goes online!

The need for more runways

LIMITED CAPACITY

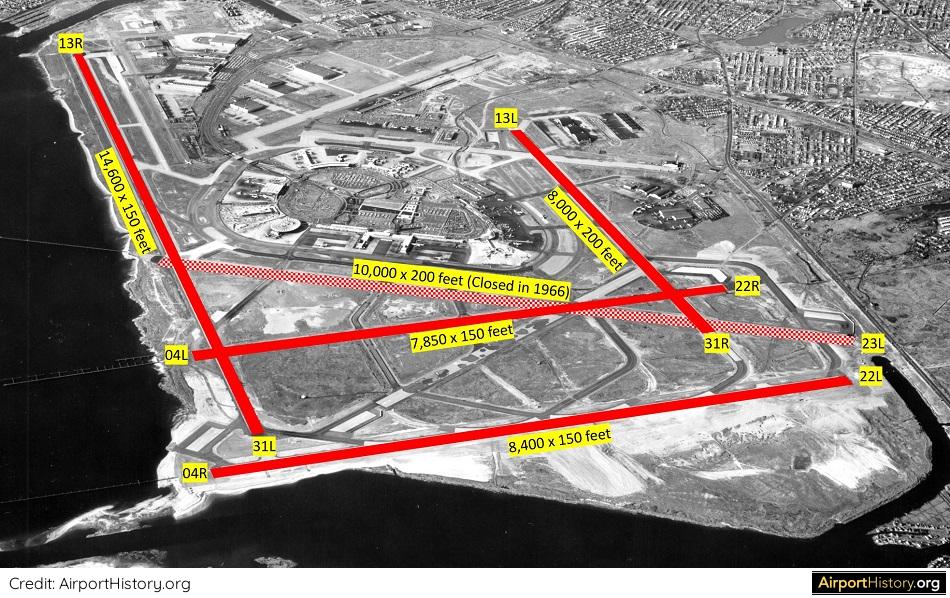

Kennedy's greatest constraint was runway capacity. However big it was, the airport was designed during WWII with smaller, lighter, piston-aircraft in mind. Due to a combination of runway layout, noise restrictions and misalignment of the runways with existing traffic patterns, the airport could only handle 68 aircraft movements an hour.

Airports such as Chicago's O'Hare--which by 1962, had surpassed Kennedy to become the world's busiest airport--Atlanta, Los Angeles and Miami had parallel runways that had a separation of over 5,000 feet (1,524 meters), allowing them to accommodate simultaneous takeoffs and landings. Kennedy's two main parallel runways used for landings--4L-22R and 4R-22L--were only 3,000 feet (914 meters) apart.

Kennedy's greatest constraint was runway capacity. However big it was, the airport was designed during WWII with smaller, lighter, piston-aircraft in mind. Due to a combination of runway layout, noise restrictions and misalignment of the runways with existing traffic patterns, the airport could only handle 68 aircraft movements an hour.

Airports such as Chicago's O'Hare--which by 1962, had surpassed Kennedy to become the world's busiest airport--Atlanta, Los Angeles and Miami had parallel runways that had a separation of over 5,000 feet (1,524 meters), allowing them to accommodate simultaneous takeoffs and landings. Kennedy's two main parallel runways used for landings--4L-22R and 4R-22L--were only 3,000 feet (914 meters) apart.

Essentially, Kennedy is a one-runway airport.

- William Crilly, senior vice president for planning at Eastern Airlines in 1968

EXPANSION INTO JAMAICA BAY

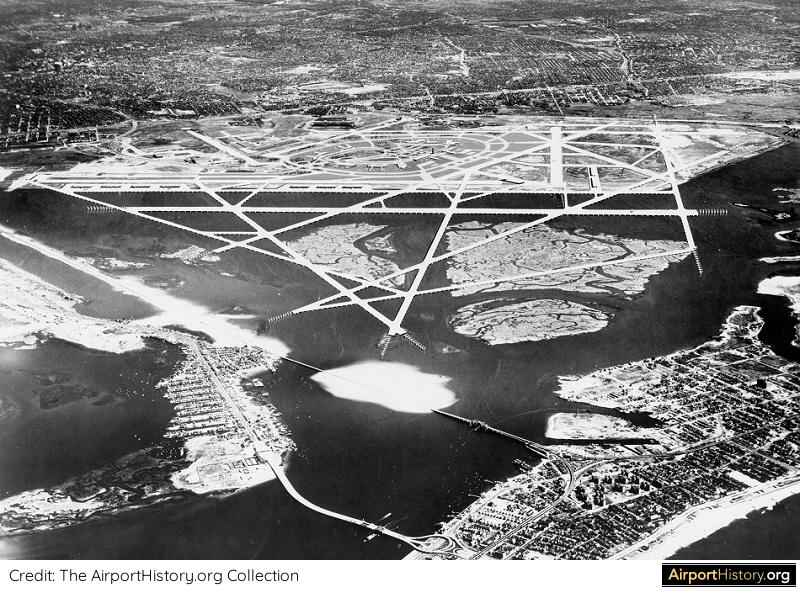

Various expansion plans were proposed to ease the congestion until a much-discussed "fourth jetport" could be built. The only solution to increase runway separation was by building new runways into Jamaica Bay, something the Port Authority had sporadically considered doing going as far back as the mid-1950s.

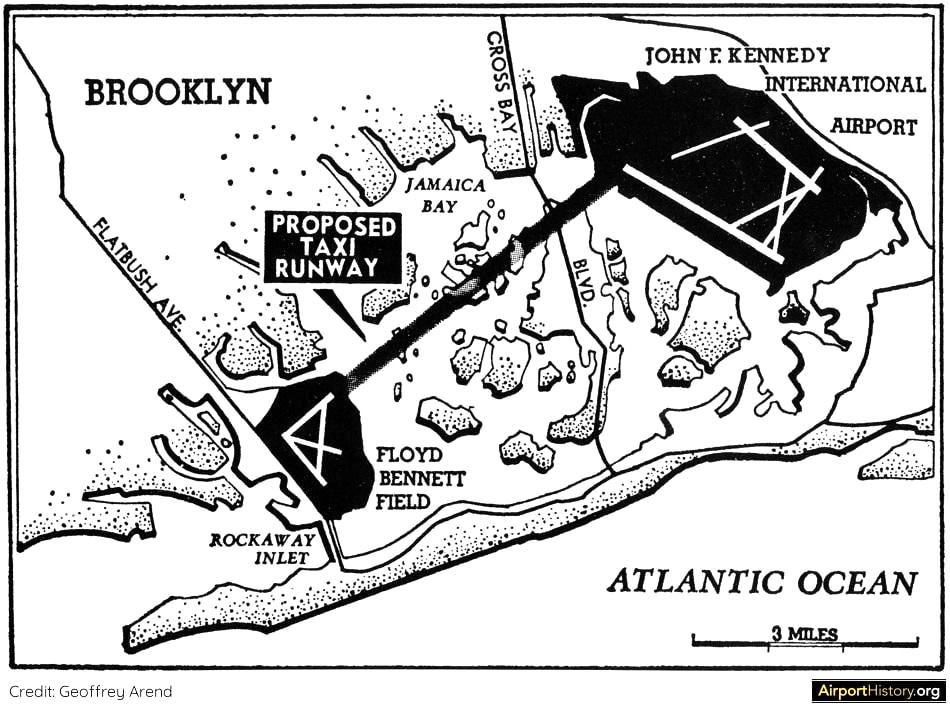

One early proposal from James Ean, Vice Chairman of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Union (PATCO), involved the construction of a combination taxiway-runway to connect JFK with Floyd Bennett Field, across the Bay in Brooklyn. In this plan Floyd Bennett would become a cargo center for Kennedy Airport.

Various expansion plans were proposed to ease the congestion until a much-discussed "fourth jetport" could be built. The only solution to increase runway separation was by building new runways into Jamaica Bay, something the Port Authority had sporadically considered doing going as far back as the mid-1950s.

One early proposal from James Ean, Vice Chairman of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Union (PATCO), involved the construction of a combination taxiway-runway to connect JFK with Floyd Bennett Field, across the Bay in Brooklyn. In this plan Floyd Bennett would become a cargo center for Kennedy Airport.

The fourth jetport controversy

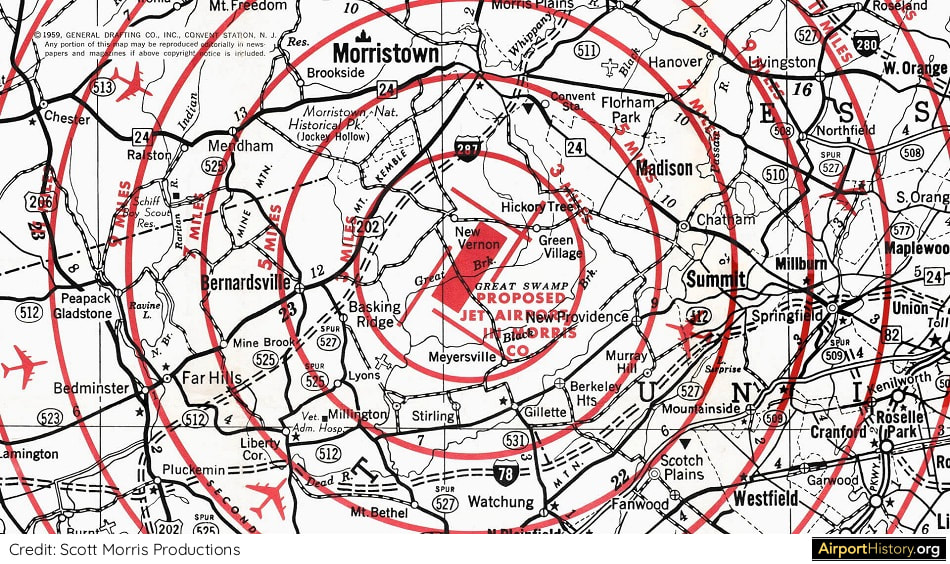

The Airlines, the Port Authority, the FAA and other stakeholders agreed that only a new airport could really alleviate the situation at JFK. The search for a potential location for the so-called "fourth jetport" had started as early as 1959.

By 1965, the Port Authority had issued four major reports on 20 possible sites for a new jetport in the metropolitan area, but only one was found to meet all its criteria. This was the Great Swamp area in Morris County, N.J., about 25 miles west of Manhattan.

By 1965, the Port Authority had issued four major reports on 20 possible sites for a new jetport in the metropolitan area, but only one was found to meet all its criteria. This was the Great Swamp area in Morris County, N.J., about 25 miles west of Manhattan.

However, opposition by New Jersey Politicians and local residents defeated this plan and part of the area became a National Wildlife Refuge.

By 1967 a location for the so-called "fourth-jeport" still hadn't been found. The expectation was it could take at least another ten years before a new airport would be ready.

As a result, the authority refocused on expanding both Kennedy and Newark airports. The fourth jetport would never be built.

By 1967 a location for the so-called "fourth-jeport" still hadn't been found. The expectation was it could take at least another ten years before a new airport would be ready.

As a result, the authority refocused on expanding both Kennedy and Newark airports. The fourth jetport would never be built.

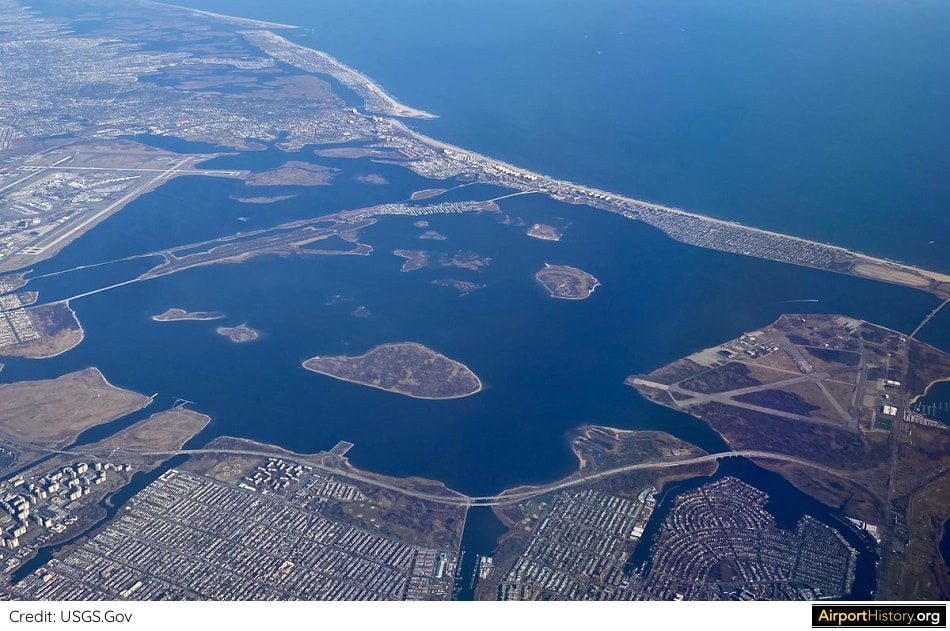

During the 1960s, planners logically looked for space in Jamaica Bay--seen here in a recent aerial--to build more runways. One plan envisaged the construction of a runway/taxiway connecting JFK (upper left) to Floyd Bennett Field (lower right), turning the latter into the cargo area for Kennedy Airport.

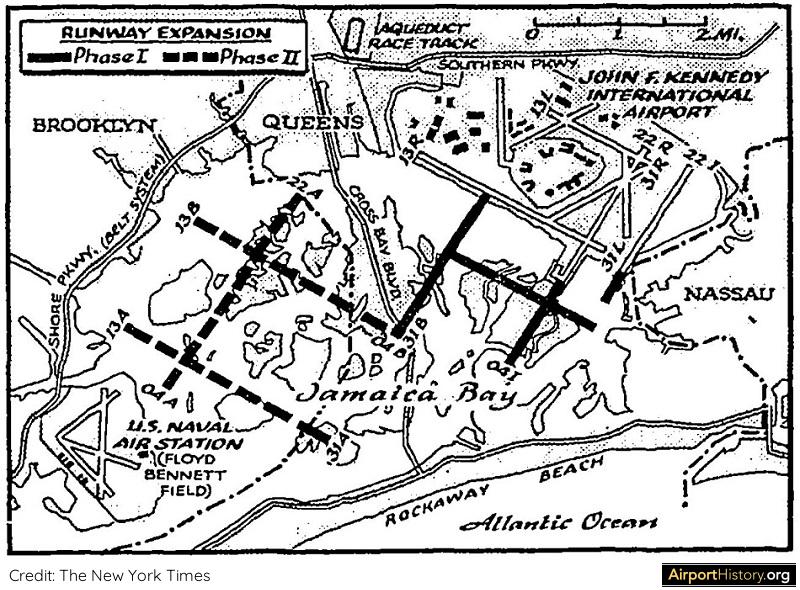

In 1966, a serious engineering study was commenced in order to assess the feasibility. Under the plan, two new runways would be constructed in Jamaica Bay, raising the total number of runways from four to six. Later on, more runways could be added as demand dictated.

However, the plans would create problems for wildlife conservation, tidal flow, and of course, noise. In addition, it would require the relocation of a highway and railway and, last but not least, a huge reorganization of the New York area airspace.

Finally, none of these proposals made it past the drawing board. Although plans for major expansion into Jamaica Bay were not realized, several construction projects were started in the late 1960s.

In 1968 Runway 4L-22R was extended to 11,351 feet (3,460 meter) with the addition of a minor landfill extension into Jamaica Bay.

However, the plans would create problems for wildlife conservation, tidal flow, and of course, noise. In addition, it would require the relocation of a highway and railway and, last but not least, a huge reorganization of the New York area airspace.

Finally, none of these proposals made it past the drawing board. Although plans for major expansion into Jamaica Bay were not realized, several construction projects were started in the late 1960s.

In 1968 Runway 4L-22R was extended to 11,351 feet (3,460 meter) with the addition of a minor landfill extension into Jamaica Bay.

GALLERY: EXPANDING JFK INTO JAMAICA BAY (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

Like this article?

Please consider supporting us with a simple donation!

Your support will help our mission to protect & preserve the heritage of the world's great airports.

The need for more gates

NEW AND EXPANDED TERMINALS

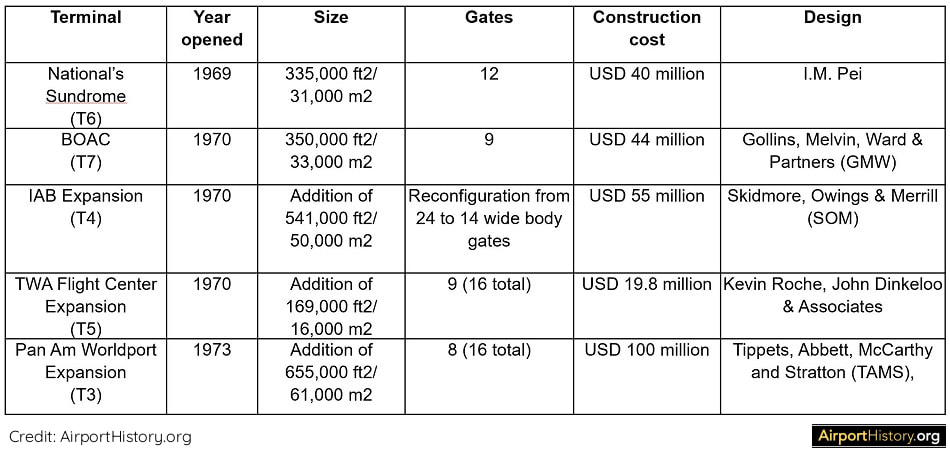

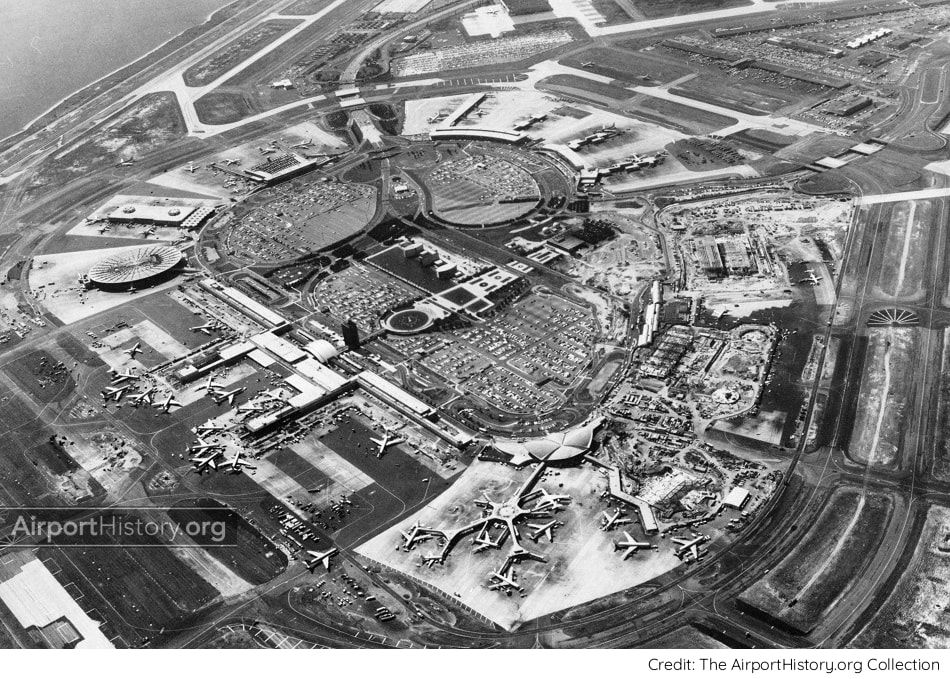

In order to address the need for more gates, in 1966, The Port Authority announced a USD 150-million plan that would see the Terminal City enlarged by 25% Projects included the construction the replacement of the original temporary terminal by a brand new facility as well as the construction of a ninth terminal.

The IAB, Pan Am terminal and TWA Flight Center meanwhile, would be greatly expanded in order to deal with the increased passenger flows as well as the upcoming jumbo jets of the 1970s.

In order to make the outward expansion of terminals possible, runway 7-25 was closed and a large section of the dual taxiway encircling Terminal City was relocated. The capacity of roadways and the parking lots would also be increased.

In order to address the need for more gates, in 1966, The Port Authority announced a USD 150-million plan that would see the Terminal City enlarged by 25% Projects included the construction the replacement of the original temporary terminal by a brand new facility as well as the construction of a ninth terminal.

The IAB, Pan Am terminal and TWA Flight Center meanwhile, would be greatly expanded in order to deal with the increased passenger flows as well as the upcoming jumbo jets of the 1970s.

In order to make the outward expansion of terminals possible, runway 7-25 was closed and a large section of the dual taxiway encircling Terminal City was relocated. The capacity of roadways and the parking lots would also be increased.

TERMINAL CITY EXPANSION FACTS

In the next chapter we will focus on the eighth and last terminal of the original Terminal City masterplan to be built: National's Sundrome!

Like this article?

Click below to support.