Published: July 10, 2019

Updated, August 5, 2019

Updated, August 5, 2019

Introduction

Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport is the major international gateway for Paris and the home base for the country’s national airline Air France, which operates a global hub-and-spoke operation from the airport.

When de Gaulle Airport opened in 1974, people praised the daring design of "Aérogare 1". However, as the airport expanded, it gained a mixed reputation among travellers, mainly due to the lengthy transfers between terminals and concourses, which are scattered far apart.

Love it or hate it, Charles de Gaulle is an impressive facility, and at the end of the day, it fulfills its role as one of the world's mega-hubs quite well. It is time to take stock and take a look back at the history of this fascinating airport!

In Part 1 of this multi-part story, we will explore the planners’ original vision for the airport, all the way back in the 1960s. What were their assumptions about the future of aviation and how did they come up with the radical design of "Aérogare 1"? Find out in Part 1 of our history on Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport!

When de Gaulle Airport opened in 1974, people praised the daring design of "Aérogare 1". However, as the airport expanded, it gained a mixed reputation among travellers, mainly due to the lengthy transfers between terminals and concourses, which are scattered far apart.

Love it or hate it, Charles de Gaulle is an impressive facility, and at the end of the day, it fulfills its role as one of the world's mega-hubs quite well. It is time to take stock and take a look back at the history of this fascinating airport!

In Part 1 of this multi-part story, we will explore the planners’ original vision for the airport, all the way back in the 1960s. What were their assumptions about the future of aviation and how did they come up with the radical design of "Aérogare 1"? Find out in Part 1 of our history on Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport!

A new airport for Paris

ECONOMIC BOOM

After World War II, France experienced an economic boom which lasted almost three decades. This period is often referred to as "Les Trente Glorieuses" or "The Glorious Thirty". During this time growth rates in the country averaged 5% per year.

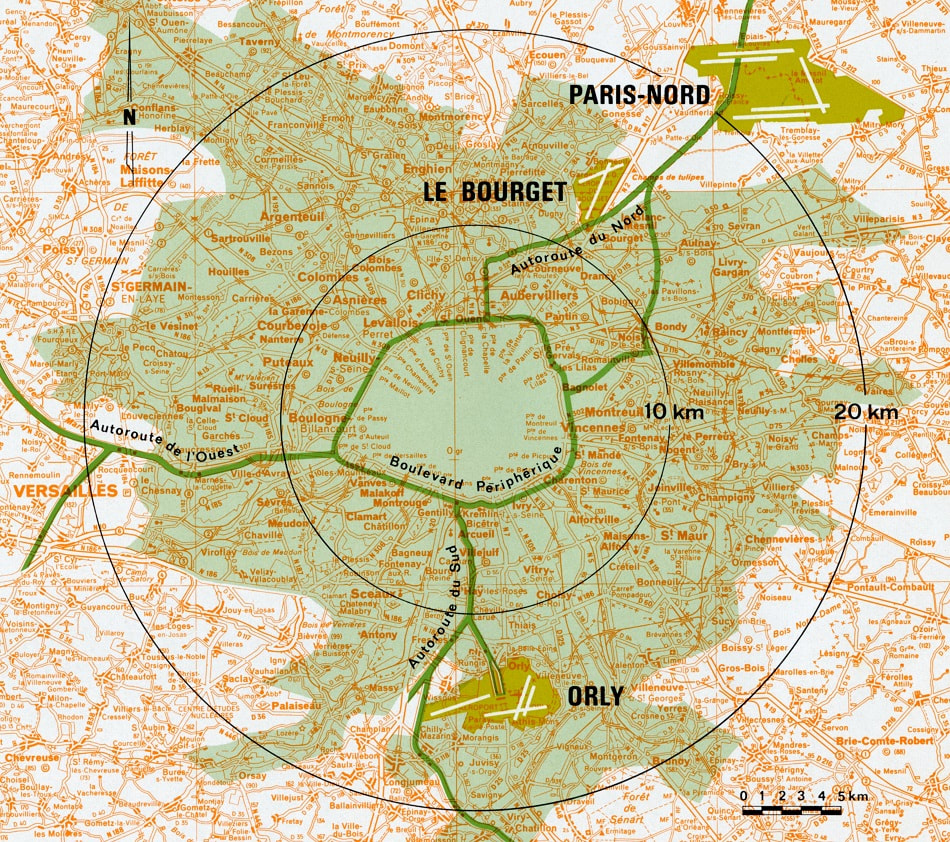

Due to the boom, air travel in the 1950s and 1960s was doubling every five to six years. The age of mass travel was about to begin. Paris' main international airports at Le Bourget and Orly both were founded during World War I and were located in relatively built-up areas.

With a maximum capacity of 3 million annual passengers, Le Bourget was the most constrained. In 1952, Air France transferred all of its operations from Le Bourget to Orly, which still had space to add runways and terminals.

However, with passenger traffic projected to grow with 15% annually for the foreseeable future, Orly would reach its saturation point of about 15 million annual passengers as soon as 1975. Thus, it was clear that a new airport would be needed. In 1957, the search for a suitable site began.

After World War II, France experienced an economic boom which lasted almost three decades. This period is often referred to as "Les Trente Glorieuses" or "The Glorious Thirty". During this time growth rates in the country averaged 5% per year.

Due to the boom, air travel in the 1950s and 1960s was doubling every five to six years. The age of mass travel was about to begin. Paris' main international airports at Le Bourget and Orly both were founded during World War I and were located in relatively built-up areas.

With a maximum capacity of 3 million annual passengers, Le Bourget was the most constrained. In 1952, Air France transferred all of its operations from Le Bourget to Orly, which still had space to add runways and terminals.

However, with passenger traffic projected to grow with 15% annually for the foreseeable future, Orly would reach its saturation point of about 15 million annual passengers as soon as 1975. Thus, it was clear that a new airport would be needed. In 1957, the search for a suitable site began.

Only one property needed to be demolished to make room for the airport.

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

In 1959, an area of only 14 miles (22 kilometers) northeast of the Paris city center called the plain of "Vieille France" (Old France) near the town of Roissy was chosen.

The area was mostly empty farmland, which was striking, considering how close it was to Paris. This was due to the historic threat of military invasions from the northeast.

Consequently, Paris was less developed in this direction. All other suitable locations for a new airport were at least 30 miles (50 kilometers) away from the city.

Only one property needed to be demolished to make room for the airport and noise was of little concern. Accessibility was ensured by the brand new six-lane A1 motorway from Paris to Brussels, which ran across the area.

In 1959, an area of only 14 miles (22 kilometers) northeast of the Paris city center called the plain of "Vieille France" (Old France) near the town of Roissy was chosen.

The area was mostly empty farmland, which was striking, considering how close it was to Paris. This was due to the historic threat of military invasions from the northeast.

Consequently, Paris was less developed in this direction. All other suitable locations for a new airport were at least 30 miles (50 kilometers) away from the city.

Only one property needed to be demolished to make room for the airport and noise was of little concern. Accessibility was ensured by the brand new six-lane A1 motorway from Paris to Brussels, which ran across the area.

|

Planning for Paris-Nord, soon renamed "Roissy" after the nearby town, began immediately and in 1964 the Interministerial Council approved the project.

At the time, a promotional brochure wrote: "What a revolution in this sudden transition from a thousand years of agriculture to jet transport! A revolution which will alter men's habits, change the face of nature, modify the environment and create thousands of jobs in an area where a few dozen men were enough to produce a rich harvest from a bountiful earth." This would not be considered very politically correct nowadays! |

A NEW SECOND AIRPORT

Due to the proximity of Roissy to the existing Le Bourget Airport, it was decided to close the latter for scheduled flights soon after the new airport would open. Thus, Roissy would not be a third Paris airport, but in fact a new second airport.

Due to the proximity of Roissy to the existing Le Bourget Airport, it was decided to close the latter for scheduled flights soon after the new airport would open. Thus, Roissy would not be a third Paris airport, but in fact a new second airport.

The planning challenge

THINKING BIG

From the outset, one thing was for certain: the new airport needed to be massive. Between 1954 and 1968, the population of the Paris region grew by 25% to 8 million inhabitants. It was projected that by 2000, the population would swell to 14 million.

In 1965, Le Bourget and Orly Airport together handled less than 5 million passengers. The demand was forecast to grow eight-fold to 40 million passengers by the mid-1980s, only 20 years away.

Under Prime Minister Georges Pompidou (1962-1968), the new airport became part of a wider effort to embark on a modernization program with the aim to catch up with more advanced countries at the time, such as Germany and the USA.

Other examples of this program are the development of La Défense, intended to provide Paris with a world class central business district; the start of the highway program; the development of major industrial areas such as Dunkirk and Le Havre; and last but not least, the development of the legendary Concorde.

In the context of this program, it was imperative that the new airport should reflect French grandeur and “savoir-faire” (know-how) in civil and aeronautical engineering.

From the outset, one thing was for certain: the new airport needed to be massive. Between 1954 and 1968, the population of the Paris region grew by 25% to 8 million inhabitants. It was projected that by 2000, the population would swell to 14 million.

In 1965, Le Bourget and Orly Airport together handled less than 5 million passengers. The demand was forecast to grow eight-fold to 40 million passengers by the mid-1980s, only 20 years away.

Under Prime Minister Georges Pompidou (1962-1968), the new airport became part of a wider effort to embark on a modernization program with the aim to catch up with more advanced countries at the time, such as Germany and the USA.

Other examples of this program are the development of La Défense, intended to provide Paris with a world class central business district; the start of the highway program; the development of major industrial areas such as Dunkirk and Le Havre; and last but not least, the development of the legendary Concorde.

In the context of this program, it was imperative that the new airport should reflect French grandeur and “savoir-faire” (know-how) in civil and aeronautical engineering.

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE NEW AGE OF AIR TRAVEL

In 1966, a team of planners and architects under the leadership of chief engineer Jacques Block began to prepare detailed plans for Paris' new airport. They wanted to use the opportunity to start with a clean slate and create one of the most efficient and sophisticated airports in Europe.

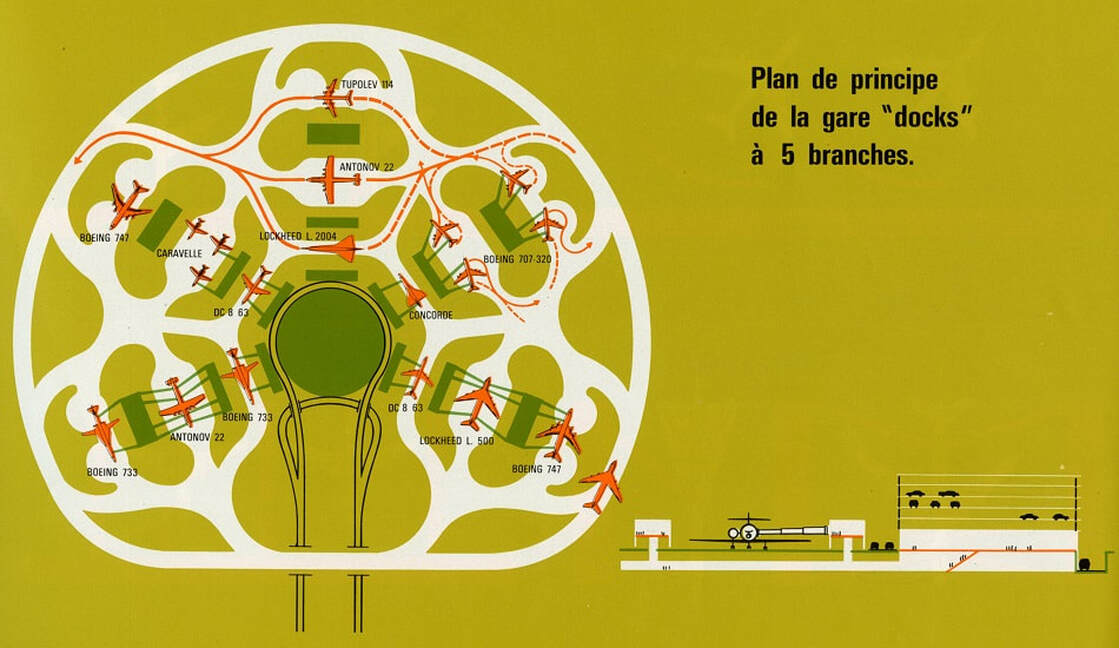

At the time, in the west, the typical jets of the day were the Boeing 707, 727 and 737 as well as the DC-8 and the DC-9, the largest of which carried under 180 passengers.

On the horizon were much larger jets such as the Boeing 747, which could carry up to 500 people in a single-class layout. The planners even had to ponder jets that could carry up to a 1,000 passengers, which were being promised by the aircraft industry at the time.

Another game-changing development was the advent of supersonic aircraft that were under development at the time in the UK/France, the USA and the USSR, and which were projected to carry a significant percentage of passengers in the 1970s and beyond.

The new airport was to be able to handle all of these different aircraft types in an efficient manner as well as in big numbers. According to projections, the airport would handle 150 takeoffs and landings at peak hours. As one runway can handle about 40 to 45 movements an hour, it meant that three to four runways that could be used simultaneously were needed.

In 1966, a team of planners and architects under the leadership of chief engineer Jacques Block began to prepare detailed plans for Paris' new airport. They wanted to use the opportunity to start with a clean slate and create one of the most efficient and sophisticated airports in Europe.

At the time, in the west, the typical jets of the day were the Boeing 707, 727 and 737 as well as the DC-8 and the DC-9, the largest of which carried under 180 passengers.

On the horizon were much larger jets such as the Boeing 747, which could carry up to 500 people in a single-class layout. The planners even had to ponder jets that could carry up to a 1,000 passengers, which were being promised by the aircraft industry at the time.

Another game-changing development was the advent of supersonic aircraft that were under development at the time in the UK/France, the USA and the USSR, and which were projected to carry a significant percentage of passengers in the 1970s and beyond.

The new airport was to be able to handle all of these different aircraft types in an efficient manner as well as in big numbers. According to projections, the airport would handle 150 takeoffs and landings at peak hours. As one runway can handle about 40 to 45 movements an hour, it meant that three to four runways that could be used simultaneously were needed.

MASS MOTORIZATION

On the landside, the challenge was no less daunting; at the time, Western Europe was in the process of mass-motorization. It was calculated that Roissy would handle 70,000 passengers a day in its final layout. In addition, an estimated 50,000 people would be employed at the airport. It was forecast that most passengers and employees would travel to the airport by car.

This meant that at peak times almost 9,000 cars per hour would travel to and from the airport each hour, enough to saturate 12 lanes of traffic. The planners would need to provide a high-capacity road system and tens of thousands of parking spaces, without wasting too much space or compromising walking distances.

On the landside, the challenge was no less daunting; at the time, Western Europe was in the process of mass-motorization. It was calculated that Roissy would handle 70,000 passengers a day in its final layout. In addition, an estimated 50,000 people would be employed at the airport. It was forecast that most passengers and employees would travel to the airport by car.

This meant that at peak times almost 9,000 cars per hour would travel to and from the airport each hour, enough to saturate 12 lanes of traffic. The planners would need to provide a high-capacity road system and tens of thousands of parking spaces, without wasting too much space or compromising walking distances.

The vision

PLANNED FOR THE FUTURE

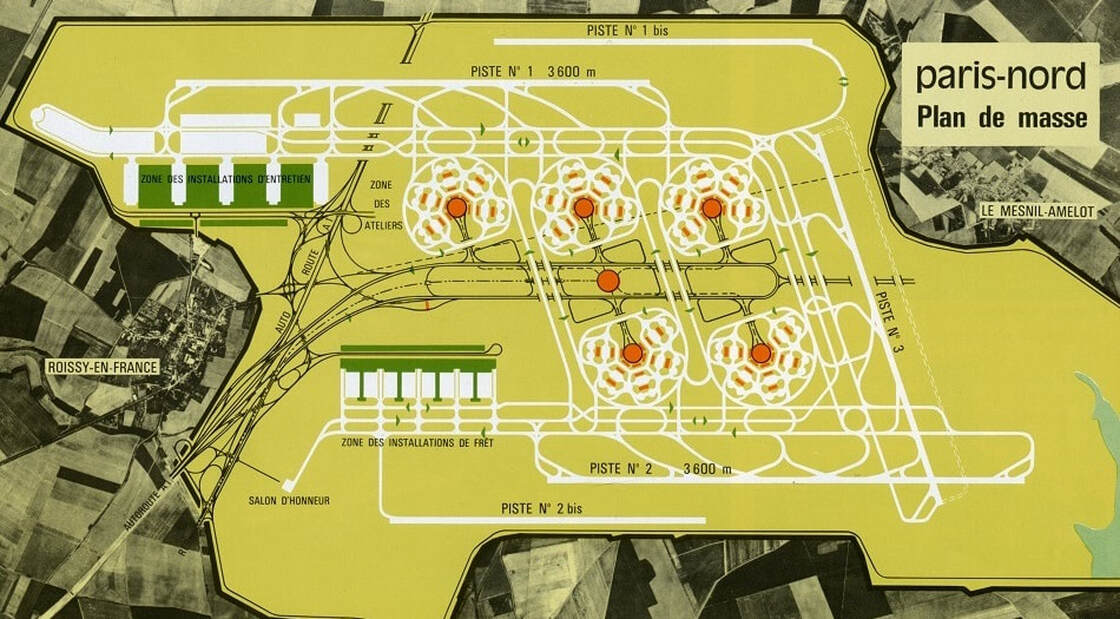

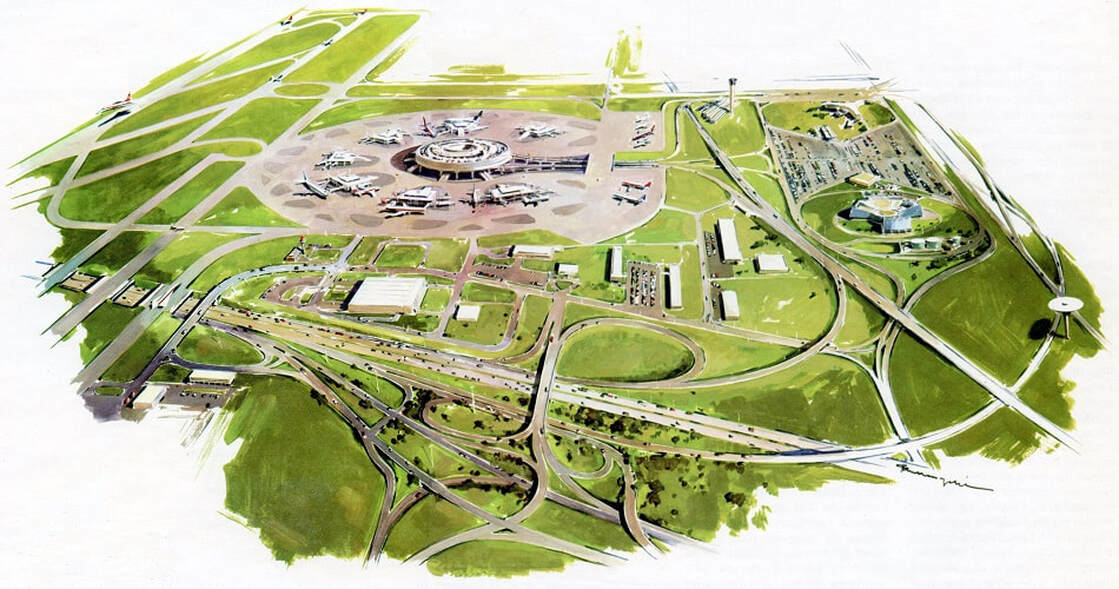

In 1966, the planners produced a master plan that was the biggest by far in the world at that time. The plan proposed a massive airport of 12.7 square miles (33 square kilometers), one third the size of the city of Paris!

In its final configuration, the airport would have a total of five runways, two pairs of parallel runways and a crosswind runway. The two main runways had a length of 11,800 feet (3,600 meters), long enough to allow the heaviest of the new wide-body jets to take off with a full load of passengers, cargo and fuel. A system of high-speed taxiways allowed aircraft to taxi at speeds of 62 mph (100 km/h).

The 747 had a length of 230 feet (69 meters). The runways and taxiways, however, were designed in such a way that they could easily accommodate jets of up to 330 feet (100 meters). If necessary, the layout of the site would enable an extension of the runways of up to 16,000 feet (5,000 meters).

These specifications made Roissy the first airport designed to handle aircraft like the A380 (and its stretched version) with ease, more than 40 years before the aircraft entered service!

In 1966, the planners produced a master plan that was the biggest by far in the world at that time. The plan proposed a massive airport of 12.7 square miles (33 square kilometers), one third the size of the city of Paris!

In its final configuration, the airport would have a total of five runways, two pairs of parallel runways and a crosswind runway. The two main runways had a length of 11,800 feet (3,600 meters), long enough to allow the heaviest of the new wide-body jets to take off with a full load of passengers, cargo and fuel. A system of high-speed taxiways allowed aircraft to taxi at speeds of 62 mph (100 km/h).

The 747 had a length of 230 feet (69 meters). The runways and taxiways, however, were designed in such a way that they could easily accommodate jets of up to 330 feet (100 meters). If necessary, the layout of the site would enable an extension of the runways of up to 16,000 feet (5,000 meters).

These specifications made Roissy the first airport designed to handle aircraft like the A380 (and its stretched version) with ease, more than 40 years before the aircraft entered service!

TERMINAL CONCEPT

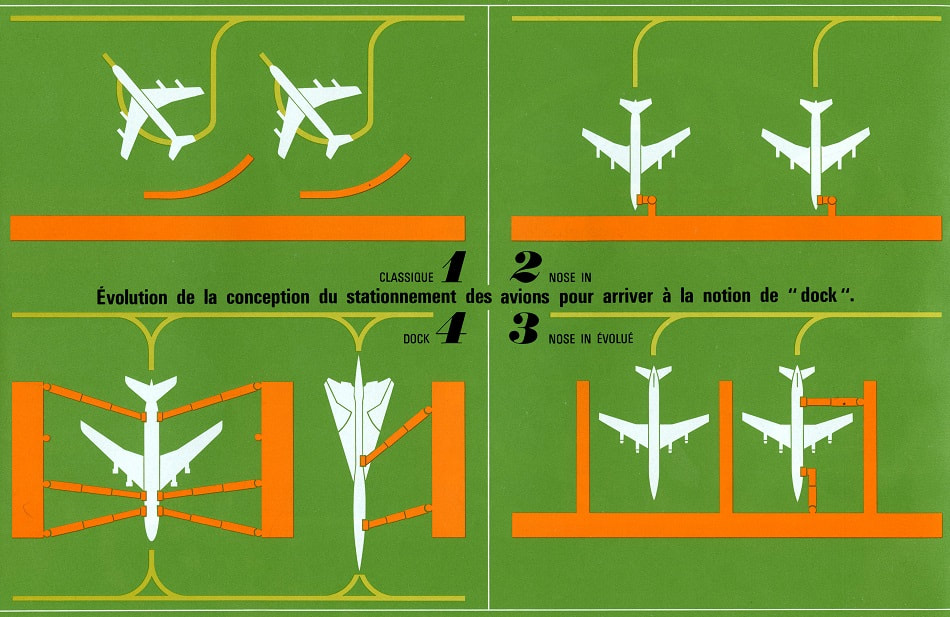

For the design of the passenger terminals, called "aérogares" in French, planners were guided by three particular requirements: walking distances between the car and the aircraft should be as short as possible; loading and servicing of aircraft must be simple and speedy; and the terminal had to be able to handle future multiple wide-body jets without congestion.

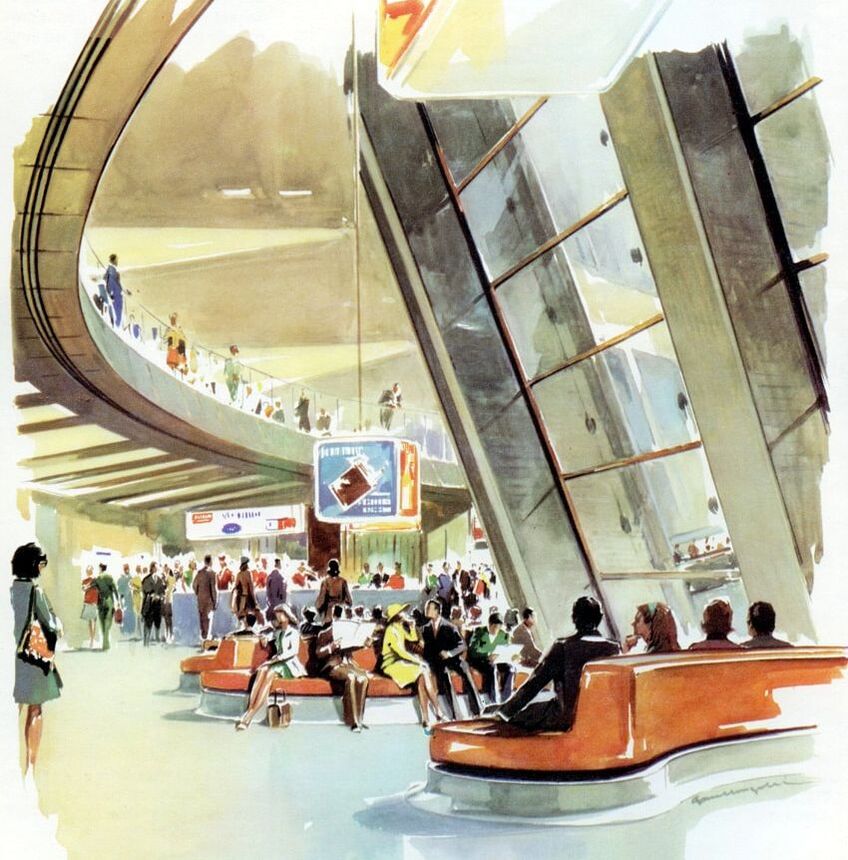

Planners took inspiration from newly built or planned Jet Age terminals in North America, namely Kansas City, Los Angeles and Toronto. In order to satisfy to the first requirement, minimizing walking distances, the planners decided to vertically stack functions—departure, arrivals, parking, airline offices, on top of each other.

They rejected the idea of a conventional rectangular terminal with concourses or piers, as they felt the walking distances were too long in some instances. Instead, they proposed a circular layout, which in theory would equalize walking distances in all directions.

THE "DOCK" SYSTEM

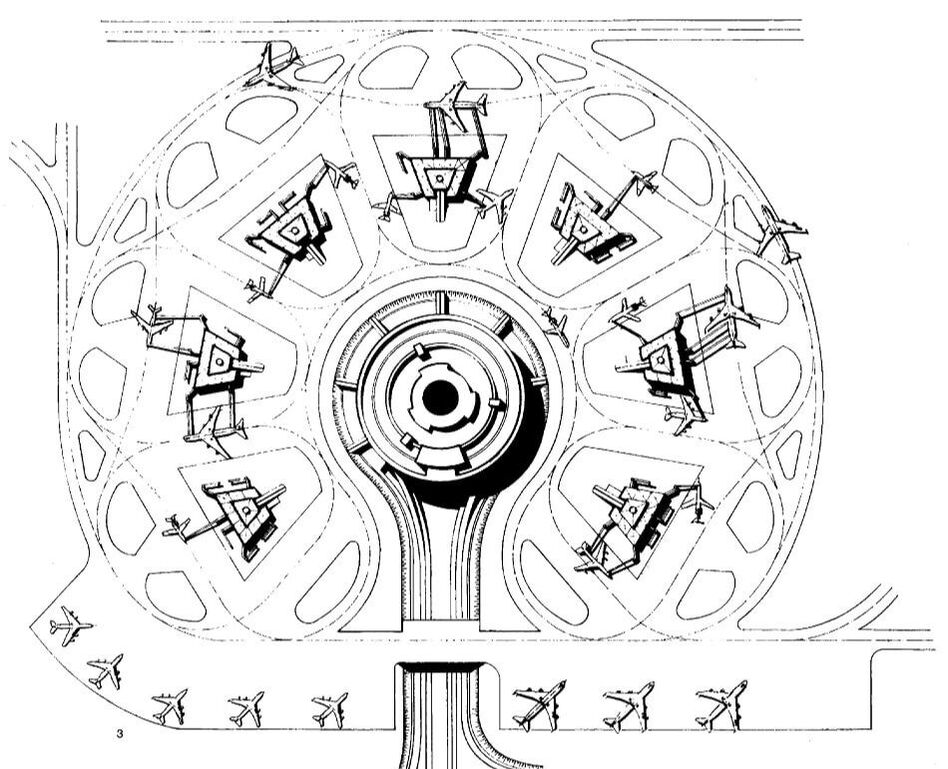

In order to enable simple and speedy boarding, the planners came up with the concept of fifteen small satellite buildings called “docks” that were organized around the circular aérogare.

For the design of the passenger terminals, called "aérogares" in French, planners were guided by three particular requirements: walking distances between the car and the aircraft should be as short as possible; loading and servicing of aircraft must be simple and speedy; and the terminal had to be able to handle future multiple wide-body jets without congestion.

Planners took inspiration from newly built or planned Jet Age terminals in North America, namely Kansas City, Los Angeles and Toronto. In order to satisfy to the first requirement, minimizing walking distances, the planners decided to vertically stack functions—departure, arrivals, parking, airline offices, on top of each other.

They rejected the idea of a conventional rectangular terminal with concourses or piers, as they felt the walking distances were too long in some instances. Instead, they proposed a circular layout, which in theory would equalize walking distances in all directions.

THE "DOCK" SYSTEM

In order to enable simple and speedy boarding, the planners came up with the concept of fifteen small satellite buildings called “docks” that were organized around the circular aérogare.

|

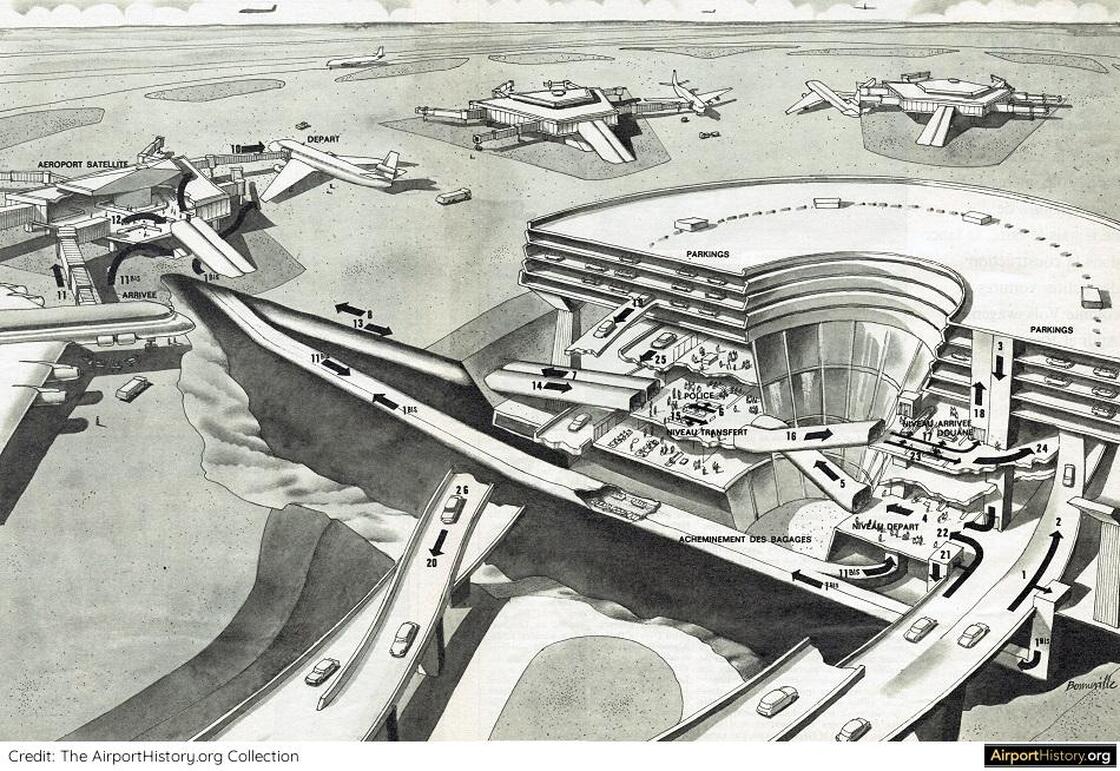

Aircraft could taxi in and out of these docks under their own power, like trains pulling in and out of a station. Aircraft did not need to backtrack, ensuring smooth circulation.

Passengers would reach the docks via underground passageways, thereby not obstructing the flow of aircraft. Passengers would board aircraft by means of boarding bridges, then still a novelty in Europe. Aircraft like the 747 could be serviced by up to six boarding bridges! Depending on the aircraft mix, between 15 and 25 aircraft could be handled simultaneously. |

EVOLUTION OF THE DOCK CONCEPT

The system of 15 dock buildings later evolved into seven wedge-shaped satellites. Each satellite was equipped with seven passenger boarding bridges, which could service up to five aircraft, including four Boeing 747 aircraft.

The system of 15 dock buildings later evolved into seven wedge-shaped satellites. Each satellite was equipped with seven passenger boarding bridges, which could service up to five aircraft, including four Boeing 747 aircraft.

|

Staying true to the dock concept, aircraft parked parallel to the satellites, enabling them to pull in and out under their own power.

The largest aircraft could be serviced by three bridges simultaneously. A further 12 remote aircraft parking positions were provided close to the terminal. The complex could handle between 8 and 10 million passengers annually. According to the original master plan, five circular passenger terminals would be constructed, generating a total maximum capacity of 50 million annual passengers. |

Enjoying this article?

Sign up to our e-mail newsletter to know when new content goes online!

THE CENTRAL UNIT

The original plan featured a huge central building located at the heart of the airport. It would connect to all the aérogares by means of a light-rail system, enabling connections between terminals.

The central building would accommodate hotels, restaurants and shops catering to passengers, visitors and employees and would house workshops and offices.

It would also be the terminus of a light rail line to Paris. Finally, the central unit had a heliport for helicopters connecting Roissy to Orly Airport and other urban airports under study in the region at the time.

The original plan featured a huge central building located at the heart of the airport. It would connect to all the aérogares by means of a light-rail system, enabling connections between terminals.

The central building would accommodate hotels, restaurants and shops catering to passengers, visitors and employees and would house workshops and offices.

It would also be the terminus of a light rail line to Paris. Finally, the central unit had a heliport for helicopters connecting Roissy to Orly Airport and other urban airports under study in the region at the time.

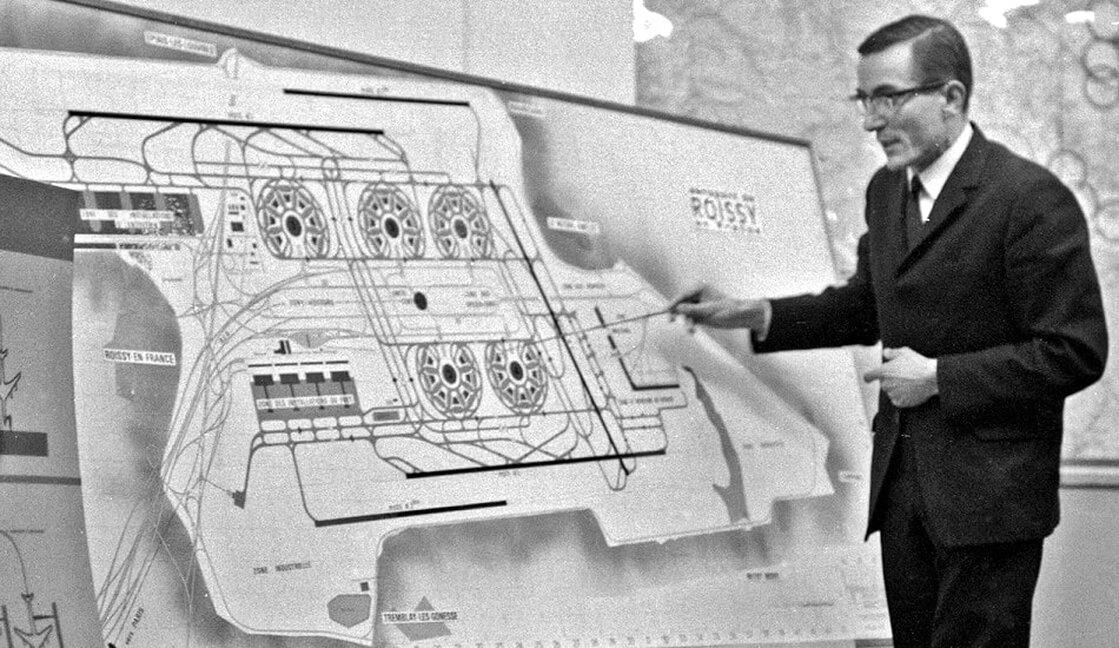

ADP chief engineer Jacques Block presents an adjusted version of the masterplan. The docks have been replaced by the satellite buildings and a large general aviation area now appears east of the crosswind runway. The large black "dot" in the middle of the airport was the central unit, a multi-functional building which would connect all terminals together through a train system. Credit: ADP

CARGO

The masterplan included a large 740 acres (300 hectares) dedicated for air cargo in the southwestern quadrant of the airport. The freight zone could be operated entirely autonomously. It would have its own banks, post office, a hotel, restaurants, offices, shops and medical services. When fully developed, the facilities would be able to handle up to 2 million tons of cargo.

MAINTENANCE

The maintenance area would be located in the northwest on the other side of the A1 motorway. In its final development, the facilities could simultaneously house 24 Boeing 707 and 32 Boeing 747 aircraft. It also offered parking stands for an additional 80 Boeing 707-size aircraft. It was expected that about 20,000 people would be employed in the maintenance area alone!

GENERAL AVIATION AND COMMERCIAL ZONE

East of the north-south runway, a general aviation area for air-taxis and business jets would be developed. It would have its own aérogare and industrial park. Finally, south of the cargo area, outside the airport perimeter, a commercial and industrial zone could be developed.

The masterplan included a large 740 acres (300 hectares) dedicated for air cargo in the southwestern quadrant of the airport. The freight zone could be operated entirely autonomously. It would have its own banks, post office, a hotel, restaurants, offices, shops and medical services. When fully developed, the facilities would be able to handle up to 2 million tons of cargo.

MAINTENANCE

The maintenance area would be located in the northwest on the other side of the A1 motorway. In its final development, the facilities could simultaneously house 24 Boeing 707 and 32 Boeing 747 aircraft. It also offered parking stands for an additional 80 Boeing 707-size aircraft. It was expected that about 20,000 people would be employed in the maintenance area alone!

GENERAL AVIATION AND COMMERCIAL ZONE

East of the north-south runway, a general aviation area for air-taxis and business jets would be developed. It would have its own aérogare and industrial park. Finally, south of the cargo area, outside the airport perimeter, a commercial and industrial zone could be developed.

Access

SEPARATION OF TRAFFIC

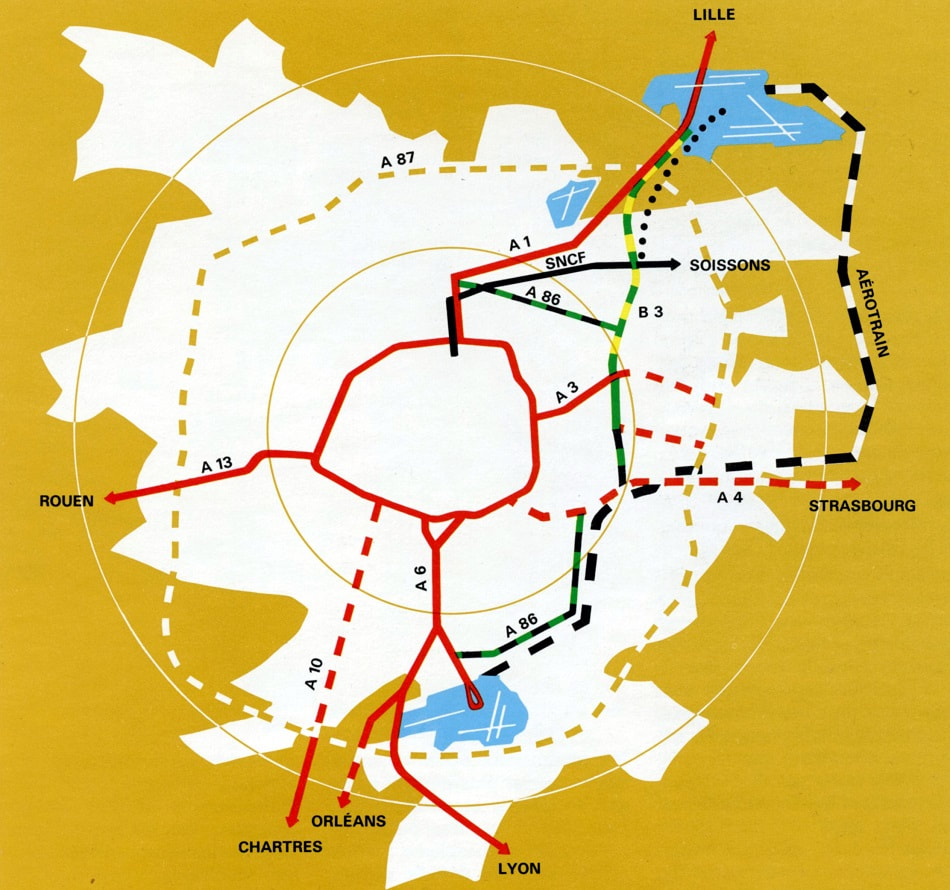

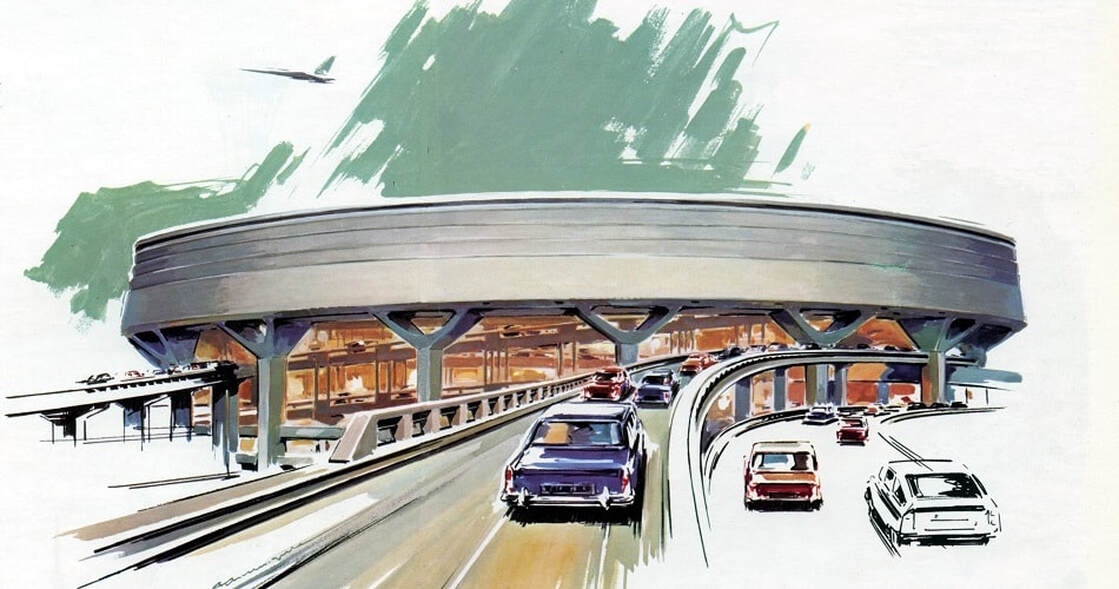

For the landside access, the planners came up with an intricate road network, the main concept of which was to completely separate vehicles carrying passenger from service traffic. Vehicles carrying passengers would exit directly from the A1 motorway, entering a spine road bisecting the airport and providing direct access to the terminals.

The layout would be very spacious and simple, as to keep traffic flowing and not confuse drivers unfamiliar with the airport area, enabling them to easily reach their departure terminal. All other traffic was carried through a separate network of secondary roads. In the final build-out, a total of 20,000 parking places were planned for passengers and visitors, with another 20,000 for employees.

For the landside access, the planners came up with an intricate road network, the main concept of which was to completely separate vehicles carrying passenger from service traffic. Vehicles carrying passengers would exit directly from the A1 motorway, entering a spine road bisecting the airport and providing direct access to the terminals.

The layout would be very spacious and simple, as to keep traffic flowing and not confuse drivers unfamiliar with the airport area, enabling them to easily reach their departure terminal. All other traffic was carried through a separate network of secondary roads. In the final build-out, a total of 20,000 parking places were planned for passengers and visitors, with another 20,000 for employees.

CONNECTIONS TO PARIS

Initially, the airport would only be connected to Paris through the motorway network. In order to deal with the projected traffic, a second motorway (the B3) would connect the airport to the east of Paris.

The six-lane A1 motorway running through the airport, would need to be doubled over a distance of several miles until the split with the B3. A few years after opening, the airport would be connected to the "Gare du Nord" train station by the RER (Réseau Express Régional), which is the suburban light rail.

Initially, the airport would only be connected to Paris through the motorway network. In order to deal with the projected traffic, a second motorway (the B3) would connect the airport to the east of Paris.

The six-lane A1 motorway running through the airport, would need to be doubled over a distance of several miles until the split with the B3. A few years after opening, the airport would be connected to the "Gare du Nord" train station by the RER (Réseau Express Régional), which is the suburban light rail.

CONNECTIONS BETWEEN PARIS-NORD AND ORLY

It was thought that Roissy would likely be the preferred airport for long-haul traffic. Both Paris-Nord and Orly would serve short-haul and medium-haul routes, enabling passengers to choose the most convenient airport relative to their place of residence or destination.

This would minimize the number of transfers between the two airports. However, it was still the expectation that a significant number of passengers would need to transfer between the two airports.

It was thought that Roissy would likely be the preferred airport for long-haul traffic. Both Paris-Nord and Orly would serve short-haul and medium-haul routes, enabling passengers to choose the most convenient airport relative to their place of residence or destination.

This would minimize the number of transfers between the two airports. However, it was still the expectation that a significant number of passengers would need to transfer between the two airports.

|

These were planned to be facilitated by helicopter and the new motorway (B3/A86) connecting the two airports and bypassing the notoriously congested Paris “Périphérique” ring road.

THE AEROTRAIN Another more exotic idea was a scheme conceived in 1969 to build an 35-mile (56-kilometer) long "Aérotrain" connection between Roissy and Orly Airport. The Aérotrain was a French-designed hovertrain that could reach speeds of over 400 kilometers per hour (250 miles per hour). There were various Aérotrain designs. One version had a JT8D jet engine--the same engine used on the early jet aircraft--mounted on the roof providing thrust. Imagine that roaring by behind your house! |

Phased development

PHASE ONE

For the first phase, planned to be opened in 1972, one runway of 11,800 feet (3,600 meters) and one circular aérogare would be built.

Phase One would also include two maintenance hangars for Air France and France's second international airline, UTA (Union de Transports Aériens). The Air France hangar would be one of the biggest in Europe with a capacity of two 747 and four DC-10 type aircraft.

In addition, cargo terminals with an annual processing capacity of 400,000 tons would be built. The catering building would be the largest in the world and had enough capacity to satisfy the requirements of two aérogares, after which it could be easily enlarged.

Finally, Phase One included a 12-mile (19-kilometer) ring road, 6.5 miles (10 kilometers) of roads for passenger traffic and 33 miles (53 kilometers) of service roads and parking for 6,900 cars.

For the first phase, planned to be opened in 1972, one runway of 11,800 feet (3,600 meters) and one circular aérogare would be built.

Phase One would also include two maintenance hangars for Air France and France's second international airline, UTA (Union de Transports Aériens). The Air France hangar would be one of the biggest in Europe with a capacity of two 747 and four DC-10 type aircraft.

In addition, cargo terminals with an annual processing capacity of 400,000 tons would be built. The catering building would be the largest in the world and had enough capacity to satisfy the requirements of two aérogares, after which it could be easily enlarged.

Finally, Phase One included a 12-mile (19-kilometer) ring road, 6.5 miles (10 kilometers) of roads for passenger traffic and 33 miles (53 kilometers) of service roads and parking for 6,900 cars.

|

THE FUTURE

At the time it was thought that a second runway and aérogare would open around 1975. The remaining runways and aérogares would need to be built soon after. In the final configuration the airport would be able to handle around 25 million annual passengers and two million tons of freight annually, a number which, according to traffic projections, would be reached around 1985. At this point, a new Paris airport would have to be built. A search for suitable sites had already been conducted around the time of the design of Roissy and several locations had been identified. |

Aérogare 1 was designed as "a machine for taking the plane.

Aérogare 1

A REVOLUTIONARY DESIGN

The centerpiece of Roissy would be "Aérogare 1" (Terminal 1). Designed by ADP architect Paul Andreu, Aérogare 1 was a circular concrete building in the architecture style called Brutalism, which was in vogue at the time. The massive building had a diamater of 630 feet (192 meters), a height of 173 feet (52.7 meters) and contained 10 levels.

The centerpiece of Roissy would be "Aérogare 1" (Terminal 1). Designed by ADP architect Paul Andreu, Aérogare 1 was a circular concrete building in the architecture style called Brutalism, which was in vogue at the time. The massive building had a diamater of 630 feet (192 meters), a height of 173 feet (52.7 meters) and contained 10 levels.

Each level would be dedicated to a single function. The basement was reserved for the baggage handling system. The second level would contain shops and restaurants, and in the future, could house a station for a train connecting to the other aérogares and other facilities.

Interestingly, this level was only added later on in the planning process. The philosophy Paul Andreu, was that Aérogare 1 was designed as "a machine for taking the plane". With the exception of some duty free shops and restaurants in the departure area. Shops, restaurants and services had no place in the public area of the terminal.

Instead, these were to be provided in the central unit. However, this “purist” vision was considered to be highly impractical, and consequently, an additional level was added containing shops, bars and restaurants that catered to airport staff, passengers and visitors.

Interestingly, this level was only added later on in the planning process. The philosophy Paul Andreu, was that Aérogare 1 was designed as "a machine for taking the plane". With the exception of some duty free shops and restaurants in the departure area. Shops, restaurants and services had no place in the public area of the terminal.

Instead, these were to be provided in the central unit. However, this “purist” vision was considered to be highly impractical, and consequently, an additional level was added containing shops, bars and restaurants that catered to airport staff, passengers and visitors.

A cutaway drawing of "Aérogare 1". Here, the Aérogare has only nine floors instead of ten as the floor with restaurants and shops had not yet been added to the design. From the transfer floor, passengers proceeded to the satellites by means of tunnels. The tunnels would descend two floors and pass underneath the platform, after which they would come up toward the satellites. Credit: The AirportHistory.org Collection

The third level was dedicated to departures and was equipped with a 159 check-in desks. Above departure was the 'transfer level', which provided access to the satellite buildings.

It also contained border and security checks as well as duty free shops, a Maxim's restaurant, a post office and lounges, facilities which were not provided in the satellites. Above the transfer level was the arrival level, which was was equipped with 8 baggage delivery belts.

It also contained border and security checks as well as duty free shops, a Maxim's restaurant, a post office and lounges, facilities which were not provided in the satellites. Above the transfer level was the arrival level, which was was equipped with 8 baggage delivery belts.

|

The choice to locate arrivals above departures was quite eccentric, although the separation between arrivals and departures itself was a novelty at the time and nothing was set in stone. Airport planning in the early Jet Age was a time of experimentation!

Passages between these three floors were provided by a tangle of covered escalators arranged through the central void of the building. Similar to the aircraft circulation, at no point would passengers hit an obstacle or need to retrace their steps. The top five floors consisted of a utilities area, parking decks with space for over 4,000 cars and airline offices. |

INTERCHANGE BETWEEN CAR AND AIRCRAFT

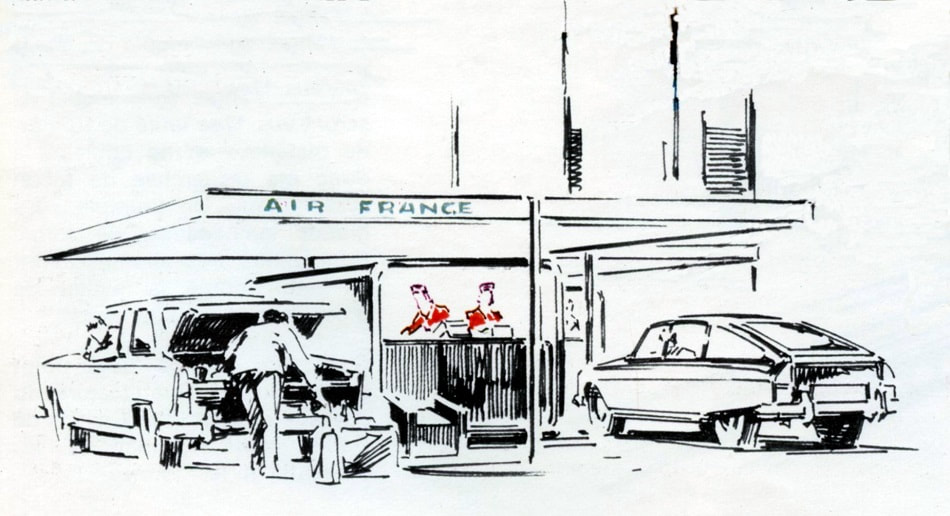

According to the architects, the main function of the terminal was to provide a break in carriage between two transport media: the car and the aircraft. It was, so to speak, an interchange.

According to the architects, the main function of the terminal was to provide a break in carriage between two transport media: the car and the aircraft. It was, so to speak, an interchange.

|

Travelers would enter the terminal with their vehicle, from which they unloaded their baggage at the drive-in check-in counters.

This permitted baggage to be transferred directly from the car to the conveyor belts carrying it to the sorting floor. The passengers would then park their car on the upper floors, driving up the spiral passages leading up to the four floors reserved for parking, after which they could take one of the rapid elevators to one of the floors open to the public. |

To be continued in Part 2!

Curious about how the airport turned out? Click here for Part 2, where we will take a tour of the spectacular Aérogare 1, as well as the other magnificent facilities!

Let us know what you think about the design of de Gaulle Airport. Share your comments below!

Let us know what you think about the design of de Gaulle Airport. Share your comments below!

Acknowledgements

This article would not have been possible without the kind assistance of Stéfania Bator, who is responsible for the Photothèque at Aéroports de Paris. Merci Stéfania!

Click here for the sources used to research this article.

Click here for the sources used to research this article.