Published: October 15, 2021

The BOAC Terminal was the ninth and last terminal to be built in Kennedy Airport's Terminal City. Several features made the BOAC terminal unique among JFK's terminals. Read the story about its design below!

I want to give thank Harriet Methven of Scott Brownrigg, aviation historian Shea Oakley, and James Sullivan for their kind assistance in preparing this article. A special thanks goes to Mark Blacklock, whose book "Recapturing the Dream," was a great inspiration for this series.

I want to give thank Harriet Methven of Scott Brownrigg, aviation historian Shea Oakley, and James Sullivan for their kind assistance in preparing this article. A special thanks goes to Mark Blacklock, whose book "Recapturing the Dream," was a great inspiration for this series.

The BOAC Terminal (1970)

BACKGROUND

Following the traffic boom in the early 1960s, JFK's Master Plan was altered to make room for a ninth terminal. Due to the scale of its operations at Kennedy, British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) was the next in line for its own facility.

BOAC was second in size to Pan American among international carriers in terms of passenger-miles flown each year. The airline carried 35% of all passengers on the JFK-Heathrow route--the busiest international route flown out of JFK.

In September 1963, BOAC commissioned the London firm of Gollins, Melvin, Ward & Partners (GMW) to design a suitable facility for the 10.5-hectare (26 acre) site. BOAC signed up Air Canada as a subtenant, which earlier had been considering sub-leasing space in National's Sundrome. The building would also be used by British West Indian Airways and Qantas.

Following the traffic boom in the early 1960s, JFK's Master Plan was altered to make room for a ninth terminal. Due to the scale of its operations at Kennedy, British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) was the next in line for its own facility.

BOAC was second in size to Pan American among international carriers in terms of passenger-miles flown each year. The airline carried 35% of all passengers on the JFK-Heathrow route--the busiest international route flown out of JFK.

In September 1963, BOAC commissioned the London firm of Gollins, Melvin, Ward & Partners (GMW) to design a suitable facility for the 10.5-hectare (26 acre) site. BOAC signed up Air Canada as a subtenant, which earlier had been considering sub-leasing space in National's Sundrome. The building would also be used by British West Indian Airways and Qantas.

Did you know?

BOAC and its successor British Airways became the first foreign airline to lease an airport terminal in the United States.

DESIGN REQUIREMENTS

In 1965, the four airlines that would use the new terminal carried 570,000 passengers to and from Kennedy Airport. By 1975, this number was expected to grow to 2 million. Thus, they required a modern facility that could accommodate growth well into the future.

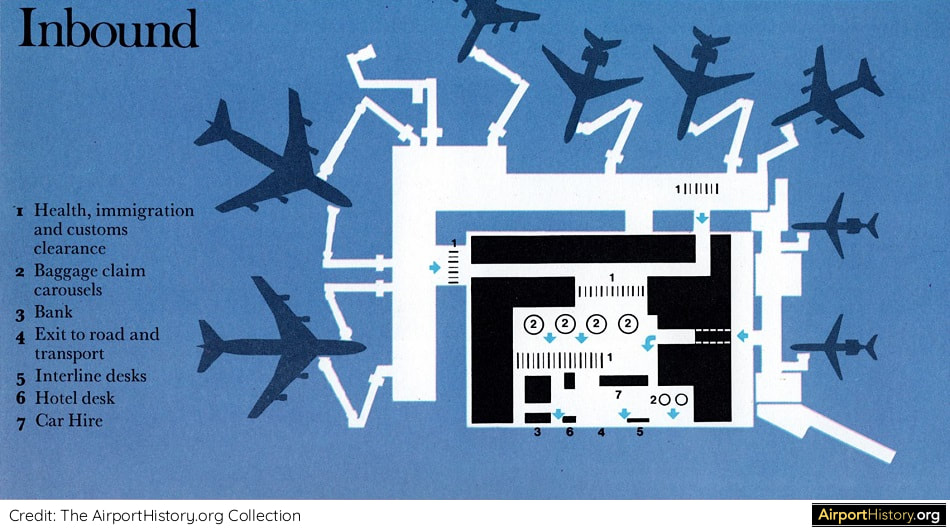

The prime considerations for the design were minimal and direct travel routes for passengers, together with ease and flexibility of administration, baggage handling and services.

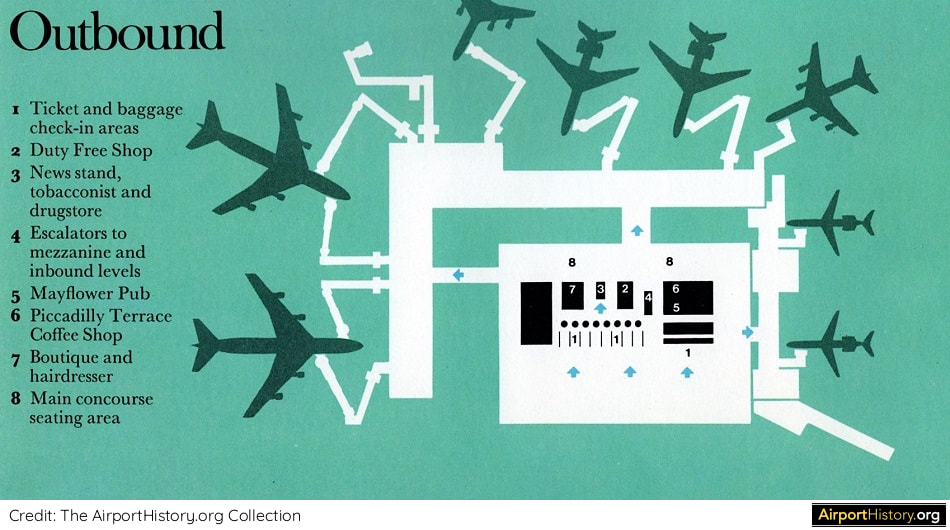

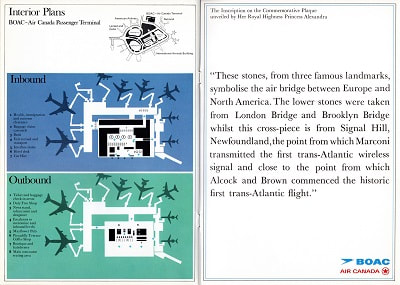

This resulted in the decision to provide a building with two operational levels; outbound passengers use the upper level and inbound the lower. A restaurant, bars, first class and VIP lounges and administrative offices were located within the mezzanine floor which would ‘span’ across the rear of the main concourse.

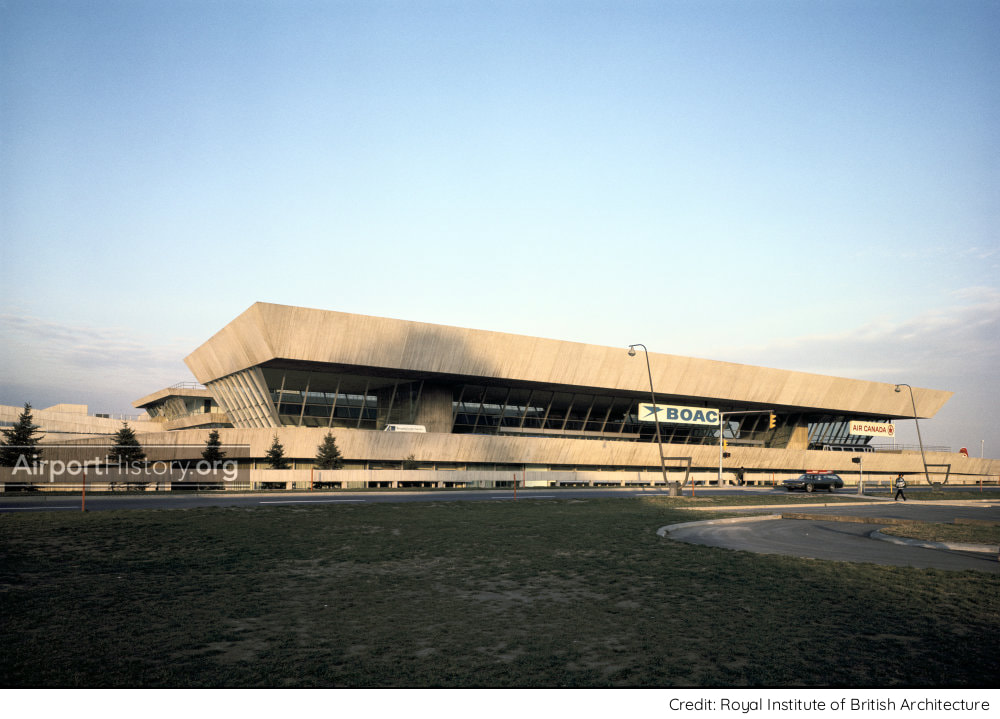

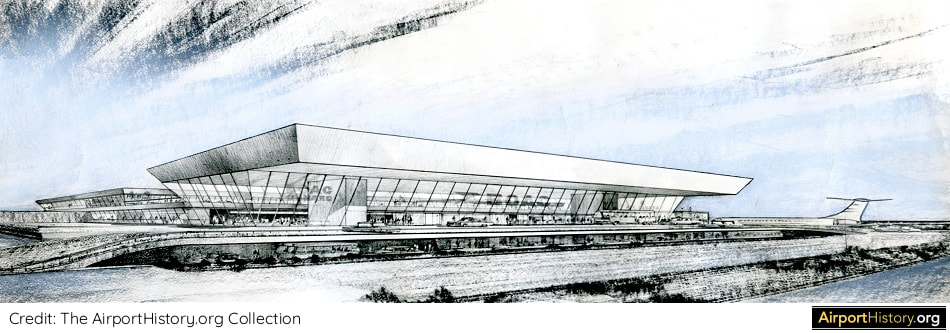

GMW designed a functional three-level structure of reinforced concrete and tinted glass, in the style of Brutalism, which was popular in Europe at the time. The terminal featured a flat overhanging roof and inward sloping walls.

In the initial design, the 300,000-ft2 (27,870-m2) terminal featured a pier which could accommodate six BOAC VC-10s.

Air Canada's three gates were directly attached to the main building. If needed, a second pier featuring five gates for BOAC could be added in the future.

A unique feature was the rooftop heliport, from where passengers could connect to and from Manhattan with helicopter service operated by New York Airways. The total investment for the terminal was estimated at USD 19.6 million.

In 1965, the four airlines that would use the new terminal carried 570,000 passengers to and from Kennedy Airport. By 1975, this number was expected to grow to 2 million. Thus, they required a modern facility that could accommodate growth well into the future.

The prime considerations for the design were minimal and direct travel routes for passengers, together with ease and flexibility of administration, baggage handling and services.

This resulted in the decision to provide a building with two operational levels; outbound passengers use the upper level and inbound the lower. A restaurant, bars, first class and VIP lounges and administrative offices were located within the mezzanine floor which would ‘span’ across the rear of the main concourse.

GMW designed a functional three-level structure of reinforced concrete and tinted glass, in the style of Brutalism, which was popular in Europe at the time. The terminal featured a flat overhanging roof and inward sloping walls.

In the initial design, the 300,000-ft2 (27,870-m2) terminal featured a pier which could accommodate six BOAC VC-10s.

Air Canada's three gates were directly attached to the main building. If needed, a second pier featuring five gates for BOAC could be added in the future.

A unique feature was the rooftop heliport, from where passengers could connect to and from Manhattan with helicopter service operated by New York Airways. The total investment for the terminal was estimated at USD 19.6 million.

"NO FUNNY SHAPE"

The project was officially announced during a lavish press event in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on Friday, April 2, 1965, the same day the VC-10 entered regular service on the London-New York and New York-Bermuda route.

A day earlier, BOAC had celebrated its 25th anniversary by announcing record gross revenues and net profits of USD 319.2 million and 19.6 million respectively.

The event was attended by BOAC chairman Sir Giles Guthrie and UK aviation minister Roy Jenkins, signifying how high profile the project was for BOAC.

During the event, Edmund F. Ward, one of the partners at GMW, commented that the planners had avoided "funny shapes" in favor of a functional design, taking a subtle jab at Pan Am's "umbrella" terminal and TWA's Flight Center, which was referred to as "the flying bra" by some.

The project was officially announced during a lavish press event in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on Friday, April 2, 1965, the same day the VC-10 entered regular service on the London-New York and New York-Bermuda route.

A day earlier, BOAC had celebrated its 25th anniversary by announcing record gross revenues and net profits of USD 319.2 million and 19.6 million respectively.

The event was attended by BOAC chairman Sir Giles Guthrie and UK aviation minister Roy Jenkins, signifying how high profile the project was for BOAC.

During the event, Edmund F. Ward, one of the partners at GMW, commented that the planners had avoided "funny shapes" in favor of a functional design, taking a subtle jab at Pan Am's "umbrella" terminal and TWA's Flight Center, which was referred to as "the flying bra" by some.

ADJUSTING FOR THE 747

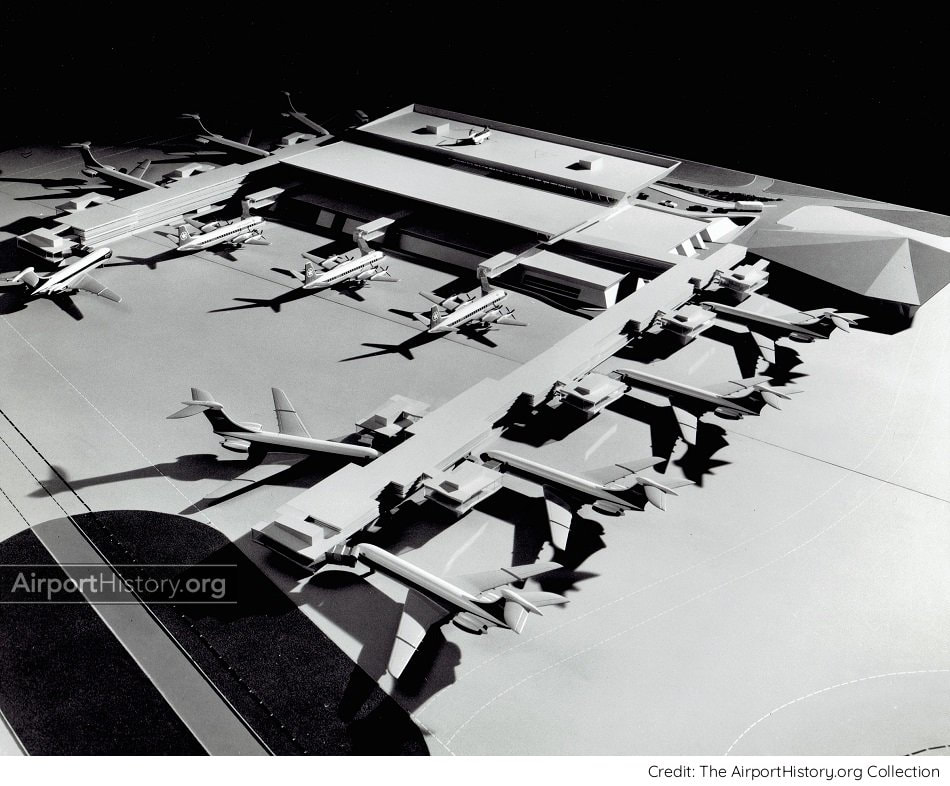

Construction was scheduled to start in January 1966. However, that year BOAC placed its first order for six Boeing 747-136 aircraft (later increased to twelve aircraft). With the 747 expected to feature prominently on the LHR-JFK route, BOAC was forced to ask the designers to rethink the gate layout.

The two piers were scrapped and replaced by a wrap-around pier, with six gates on the western and northern sides for BOAC and three gates for Air Canada’s on the eastern side. This improved aircraft manoeuvrability on the ramp and reduced the average walking distance for passengers, while offering larger gate lounges.

UNIQUE BOARDING BRIDGES

BOAC's section boasted three 747 capable gates, with boarding bridges connecting to both the port side and the starboard side of the aircraft, a unique feature only to be found at a few airports and terminals at the time. The remaining three VC10-capable gates would be served by a single boarding bridge.

Another unique feature was the use of luffing bridges at the international gates. These moved vertically between the arrivals and the departure level at the terminal interface, ensuring separation of arriving and departing passengers without the need for additional sterile corridors.

Construction was scheduled to start in January 1966. However, that year BOAC placed its first order for six Boeing 747-136 aircraft (later increased to twelve aircraft). With the 747 expected to feature prominently on the LHR-JFK route, BOAC was forced to ask the designers to rethink the gate layout.

The two piers were scrapped and replaced by a wrap-around pier, with six gates on the western and northern sides for BOAC and three gates for Air Canada’s on the eastern side. This improved aircraft manoeuvrability on the ramp and reduced the average walking distance for passengers, while offering larger gate lounges.

UNIQUE BOARDING BRIDGES

BOAC's section boasted three 747 capable gates, with boarding bridges connecting to both the port side and the starboard side of the aircraft, a unique feature only to be found at a few airports and terminals at the time. The remaining three VC10-capable gates would be served by a single boarding bridge.

Another unique feature was the use of luffing bridges at the international gates. These moved vertically between the arrivals and the departure level at the terminal interface, ensuring separation of arriving and departing passengers without the need for additional sterile corridors.

GALLERY: AERIAL AND EXTERIOR IMAGES (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

Enjoying this article?

Sign up to our e-mail newsletter to know when new content goes online!

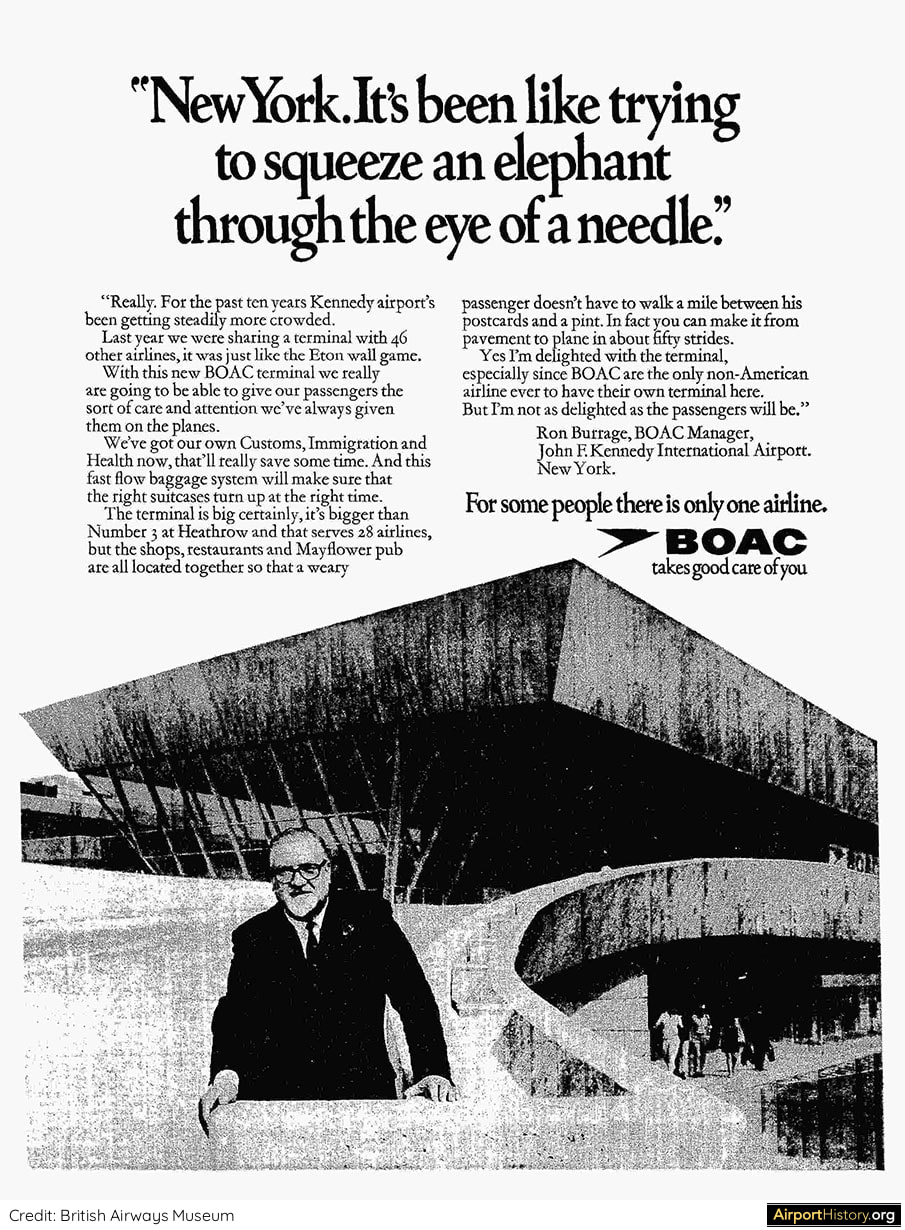

“A weary passengers doesn't have to walk a mile between his postcard and a pint.”

- A BOAC print ad boasting the new terminal.

LAYOUT AND FACILITIES

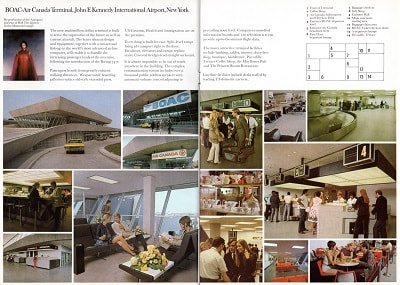

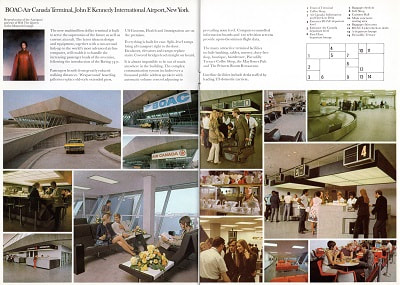

BOACs check-in area was located on the western side of the lobby. Check-in and baggage acceptance were planned on the supermarket flow through principles, which pre-sorted both the passengers and their baggage by flight number.

Behind it were a small concession arcade and nursery.

Air Canada's facilities were located on the eastern side. The airline used a conventional layout for the check-in desks and baggage handling facilities. Situated behind was the Maple Leaf Lounge, the Piccadilly Terrace coffee shop, and the Mayflower pub.

BOACs check-in area was located on the western side of the lobby. Check-in and baggage acceptance were planned on the supermarket flow through principles, which pre-sorted both the passengers and their baggage by flight number.

Behind it were a small concession arcade and nursery.

Air Canada's facilities were located on the eastern side. The airline used a conventional layout for the check-in desks and baggage handling facilities. Situated behind was the Maple Leaf Lounge, the Piccadilly Terrace coffee shop, and the Mayflower pub.

The mezzanine contained BOAC’s Monarch Lounge for first-class passengers, a cocktail bar, the Princess Room restaurant, the press room, offices, and a VIP suite.

The lower level accommodated the FIS, separate baggage rooms for BOAC and Air Canada, the public arrivals lobby with domestic baggage reclaim at the eastern end, offices, crew and plant rooms, a staff canteen and the terminal’s main kitchen.

There was also an observation deck atop the north gate concourse, but the concept of a rooftop heliport was scrapped.

With New York Airways already operating from the terminals of Pan Am, TWA and American, BOAC would have to subsidize the additional service, something the airline couldn't justify.

The lower level accommodated the FIS, separate baggage rooms for BOAC and Air Canada, the public arrivals lobby with domestic baggage reclaim at the eastern end, offices, crew and plant rooms, a staff canteen and the terminal’s main kitchen.

There was also an observation deck atop the north gate concourse, but the concept of a rooftop heliport was scrapped.

With New York Airways already operating from the terminals of Pan Am, TWA and American, BOAC would have to subsidize the additional service, something the airline couldn't justify.

GALLERY: INTERIOR IMAGES (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

Like this article?

Support us by donating $9.95 and receive a fantastic download!

Your support will help our mission to protect & preserve the heritage of the world's great airports.

As a token of our thanks you will receive a digital download of a fascinating 12-page 1970 brochure commemorating the opening of the BOAC Terminal!

Or you can make a simple donation.

Click below to support.

|

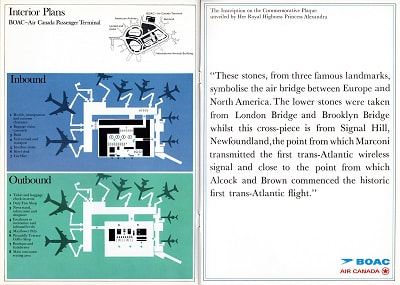

OPENING

After the redesign, which increased the floor area to 335,000 ft2 (31,122 m2), construction started in January 1967, but was delayed by industrial disputes and several fires including an arson attack. The terminal finally opened on June 30, 1970, with a total price tag of USD 56 million, almost three times higher than the original budget. A few weeks later, on August 26, there was another arson attack, which caused USD 1 million of damage and necessitated the closure of three gates. On September 24, the terminal was officially dedicated by UK Royal Princess Alexandra, a first cousin of Queen Elizabeth II. In In 1971, GMW received the annual award of the US Concrete Industry Board for the BOAC terminal for the originality and application of concrete in design and construction. |

The Inscription on the Commemorative Plaque unveiled by Her Royal Highness Princess Alexandra:

"These stones from three famous landmarks, symbolise the air bridge between Europe and North America. The lower stones were taken from London Bridge and Brooklyn Bridge whilst this cross-piece is from Signal Hill, Newfoundland, the point from which Marconi transmitted the first trans-Atlantic wireless signal and close to the point from which Alcock and Brown commenced the historic first trans-Atlantic flight."

"These stones from three famous landmarks, symbolise the air bridge between Europe and North America. The lower stones were taken from London Bridge and Brooklyn Bridge whilst this cross-piece is from Signal Hill, Newfoundland, the point from which Marconi transmitted the first trans-Atlantic wireless signal and close to the point from which Alcock and Brown commenced the historic first trans-Atlantic flight."

FIRST YEARS

In the first years, the BOAC Terminal, later renamed Terminal 7, was an important stopover and connection point, with flights to/from London Heathrow, Manchester, and Glasgow (Prestwick), Bermuda (onward to Antigua and Barbados), Montego Bay (onward to Kingston), and Los Angeles (onward to Honolulu, Fiji and Sydney).

In 1974 BOAC merged with British European Airways (BEA) to form British Airways. A highlight for the terminal was start of supersonic services at JFK in November 1977. A dedicated lounge for Concorde passengers was created at Gate 1.

In the first years, the BOAC Terminal, later renamed Terminal 7, was an important stopover and connection point, with flights to/from London Heathrow, Manchester, and Glasgow (Prestwick), Bermuda (onward to Antigua and Barbados), Montego Bay (onward to Kingston), and Los Angeles (onward to Honolulu, Fiji and Sydney).

In 1974 BOAC merged with British European Airways (BEA) to form British Airways. A highlight for the terminal was start of supersonic services at JFK in November 1977. A dedicated lounge for Concorde passengers was created at Gate 1.

In future chapters, we will revisit the British Airways Terminal for developments in the 1980s until its eventual planned demise. In the following chapters we will explore the expansion of the IAB, Pan Am terminal and TWA Flight Center!

Do you have memories of the Sundrome? Share them below!

Do you have memories of the Sundrome? Share them below!

Like this article?

Support us by donating $9.95 and receive a fantastic download!

Your support will help our mission to protect & preserve the heritage of the world's great airports.

As a token of our thanks you will receive a digital download of a fascinating 12-page 1970 brochure commemorating the opening of the BOAC Terminal!

Or you can make a simple donation.

Click below to support.