|

On September 21st, it will have been 40 years ago that Atlanta's Midfield Terminal Complex opened for traffic.

Its characteristic layout of long concourses, perpendicular to the runway and connected by an underground people mover system, ensured a highly efficient movement of both passengers and aircraft. For the decades that followed, Atlanta would become the gold standard for the design of hub airports. However, did you know that the design evolved from a plan that was very similar to the original plan for Dallas/Fort Worth Airport? It's only due to project delays that we got the the "ATL" we know today. Read all about it below!

THE NEED FOR A NEW TERMINAL

Atlanta's previous terminal was completed in 1961. It was originally designed for 13.5 million passengers, a level that was already reached in the mid-1960s. In 1967 the city decided it was time to build a new terminal and modify the existing one. In November 1967 a consortium of architects commenced the difficult task of designing the world's largest air passenger terminal building. Everyone--the airlines, the two participating joint venture planning firms and even airline pilots--submitted ideas for the terminal design. The architects compiled sixty concepts into a briefing book. Those were narrowed down to ten for a more detailed study. INSPIRATION FROM TEXAS In the late 1960s the primary consideration in airport design was passenger convenience in the form of short walking distances between parking facilities and aircraft gates. In December 1967, the master plan for the newly planned Dallas/Fort Worth Regional Airport was published. Prepared by Walther Prokosch, who also designed the original Pan Am terminal and the Worldport expansion, the plan proposed the concept of 20 self-contained terminals along a connecting roadway.

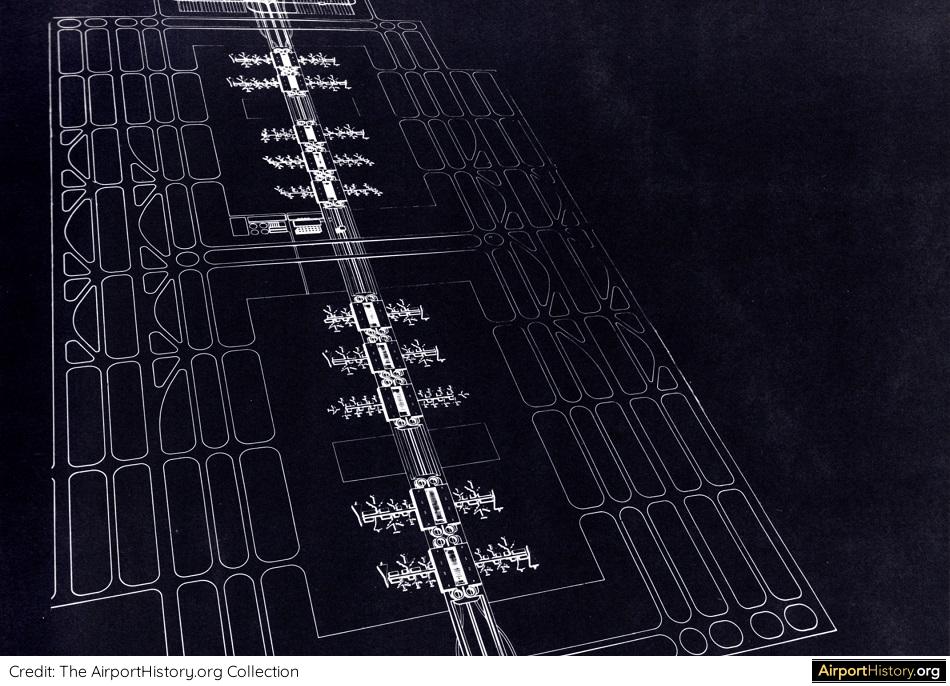

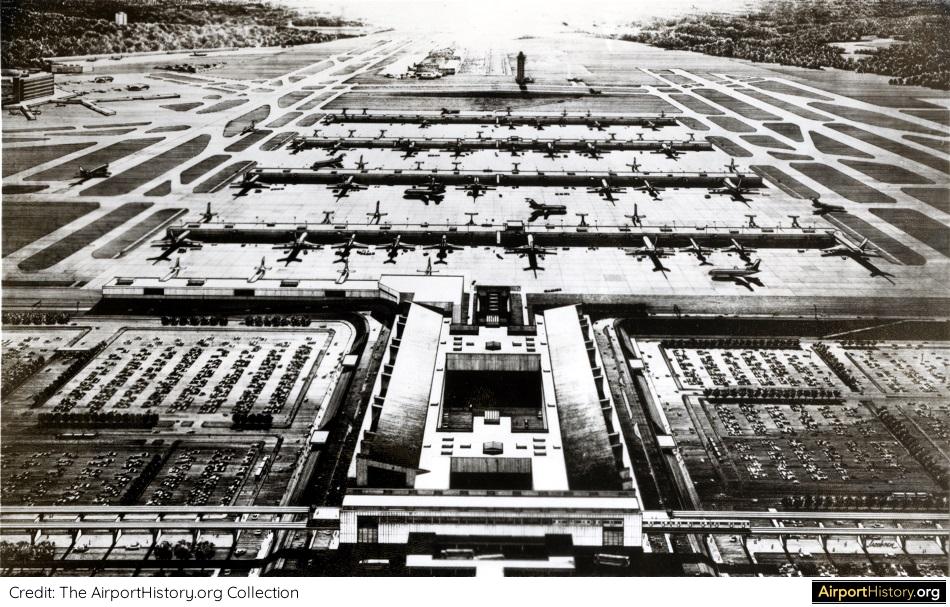

An artist's impression of the original master plan for the new Dallas/Fort Worth Regional Airport. In a way, the plan can be seen as an optimized version of New York Kennedy's Terminal City but also LAX, with each airline operating its own facilities. Later on, the terminals were changed to a semi-circular shape.

Airlines praised the model. They loved the idea of operating their own airport facilities and the small airport convenience the "mini-terminals" brought.

Thus, the Atlanta architects developed their own version of the DFW plan. They conceived the midfield complex as a series of sixteen terminal units along structural, double-decked roadways of Interstate 85 on the west. The roadways met on the east side and continued at ground level to Interstate 75. Each terminal was self-contained with aircraft gates, ticketing and baggage facilities. The 600-foot (183-meter) central strip was dedicated to roadways and parking garages. A people mover system ran through the upper level of each terminal, parallel to the roadways. Other features included a hotel and an automated sorting system for mail and baggage.

SLIPPING TIMELINE: A BLESSING IN DISGUISE

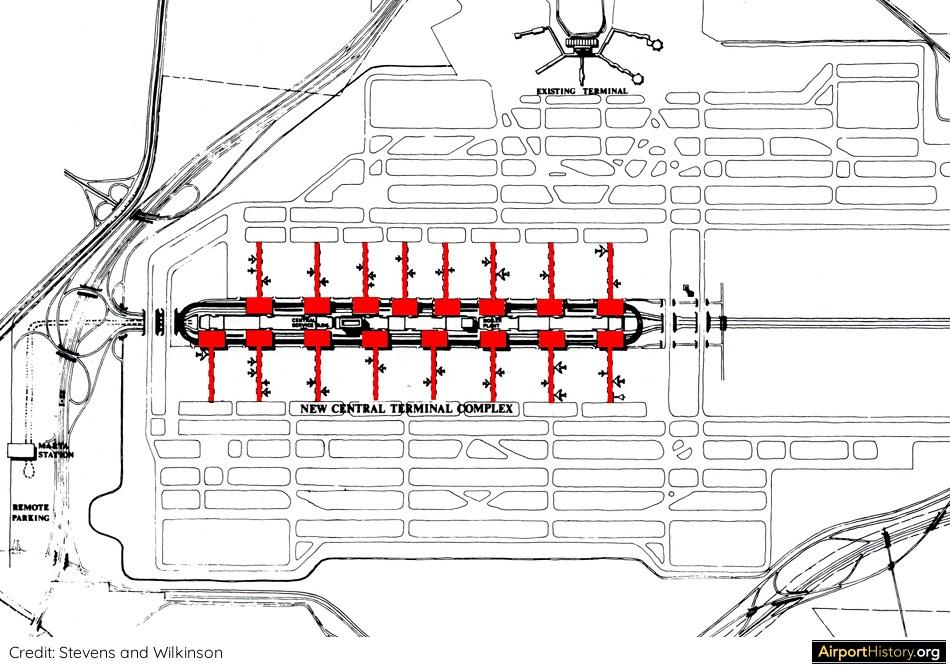

Initially the completion date for the new midfield expansion was 1972. However, the timetable slipped by years due to airline politics, economic downturns, financing issues as well as discussions about a second airport. This had a major advantage: there was ample time to adjust and fine-tune the design for the midfield complex. By 1971 the original design was still more or less intact. However, the central area had been reduced from 600 to 200 feet and the people mover was no longer elevated. The layout was very much tailored to Atlanta's "O&D" (origin and destination) passengers. However, at the time 70% of passengers changed flights at the airport. With the proposed design, most transfer passengers would have to change terminals in order to catch their onward flight. Even cities that had large volumes of connecting passengers had never specifically addressed this situation: they had merely adapted standard airport designs. Therefore, no precedent existed from which Atlanta's planners could draw.

A BREAKTHROUGH

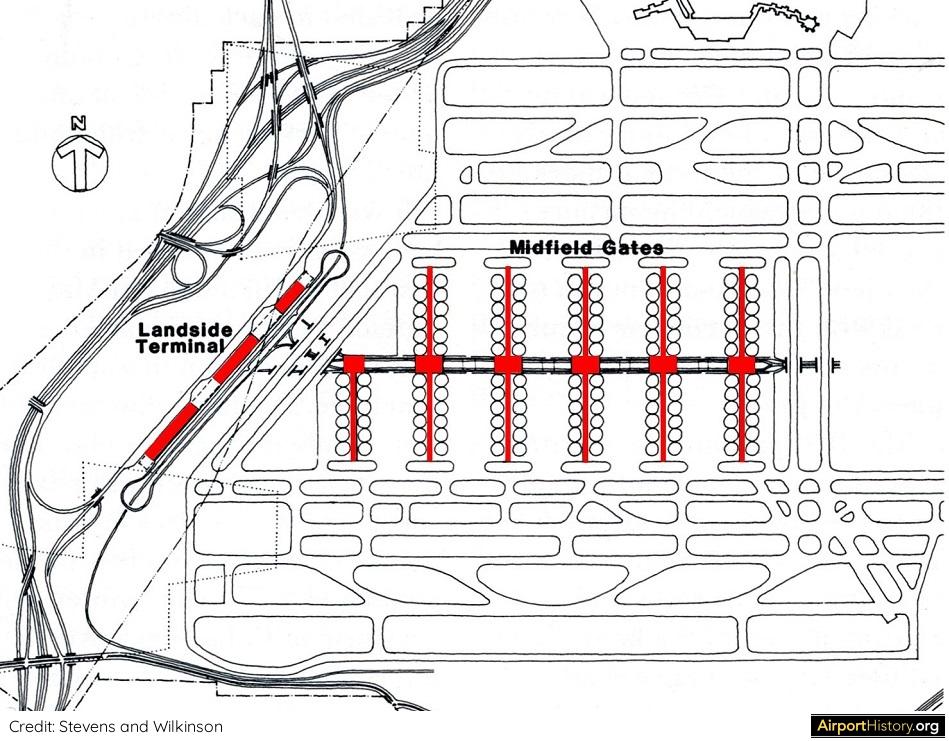

In a conceptual breakthrough in 1973, the complex had been split into two distinct sections, airside terminals with aircraft parking gates and landside terminals for ticketing and baggage. Roadways and parking were moved away from the aircraft gates and concentrated around the landside facilities, making the roadway system much simpler, while still creating curb space for hundreds of cars per hour. Although the separation was not considered particularly significant at the time, it marked the point at which the airport veered away from its "drive to the plane" stance and began to deal with the particular requirements of a transfer airport. Originating and terminating passengers would shuttle between the terminals and six airside concourses on a sunken but exposed people mover system, the sole means of transportation within the complex. As ticketing and baggage facilities no longer had to be provided in each airside terminal, more aircraft gates could be added. The elimination of roadways and parking freed additional space.

LAST BUT NOT LEAST

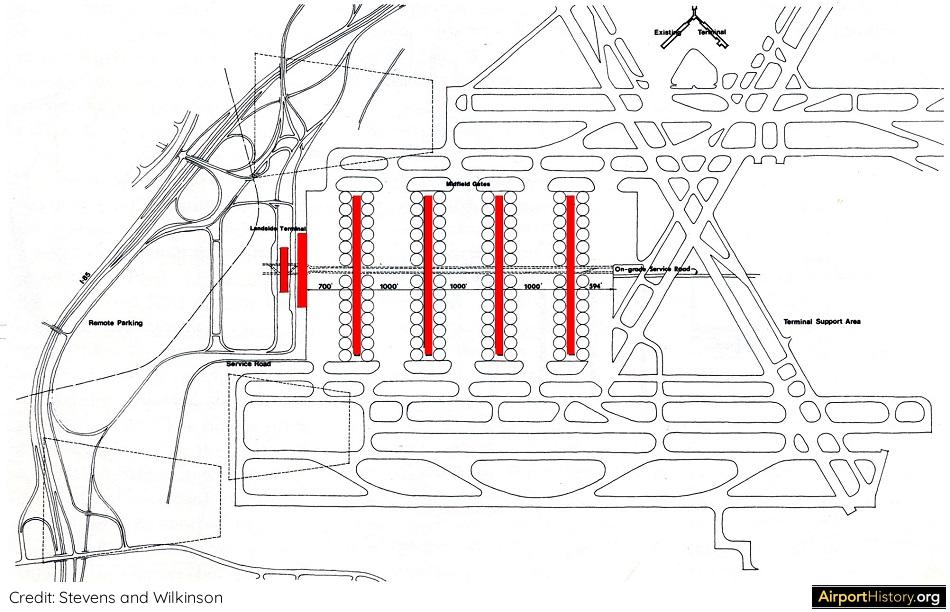

Another major change was to come in the winter of 1975. Due to an ice storm at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, the Airtrans people mover system, the ground level people mover that had been a model for Atlanta's planning, became paralyzed. The designers realized that Atlanta's system would be vulnerable under similar conditions. It was a risk that airlines would not accept. Thus, during an intense brainstorming session Delta's facility department recommended covering the "ditch" that contained the people mover system, thereby protecting it from the elements. Putting the people mover underground also removed the barrier between the north and south runway systems and eliminated the need for costly taxiway bridges. Also, the taxiways that in earlier layouts had separated the landside and airside terminals could be eliminated. Next the Delta team recommended that two parallel terminals replace the three landside linear landside buildings. This move, coupled with the removal of the taxiways, allowed the half-concourse to become a full concourse, adding twelve gates.

THE FINAL STEP IN CREATING THE "ATL" WE KNOW TODAY

A final critical step was to divide the people mover tunnel into two chambers and separate them to allow for a pedestrian mall in between. Lastly, the planners re-positioned the terminals from a north-south to an east-west alignment and placed them back to back. The number of concourses was reduced to four domestic concourses boasting 26 gates each, with space to build a fifth concourse. An international concourse was added adjacent to the north terminal.

On April 18th, 1977, the contracts for construction of the terminal building and the people mover were awarded and construction could begin, almost ten years after the start of the design process. All good things take time!

For this blog the fantastic 1989 book "A Dream Takes Flight" by Betsy Braden & Paul Hagan was a huge inspiration. I highly recommend this book to anyone who wants to know more about the history of Atlanta Airport pre-1990.

We hope you enjoyed this little piece of history on the development of Atlanta's Midfield Terminal. In the future we are also planning a full multi-part history on the development of Atlanta Hartsfield-Jackson Airport. Sign up below to know when new content is released!

More airport articles: Click here

Want more stunning airport photos & stories?

Sign up to our newsletter below to know when new content goes online!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I want to give a special thanks to Marie Force of the Delta Flight Museum for her assistance in preparing this article.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

With a title inspired by the setting of the iconic 70s film "Airport", this blog is the ultimate destination for airport history fans.

Categories

All

About me

Marnix (Max) Groot Founder of AirportHistory.org. Max is an airport development expert and historian. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed