|

The TWA Flight Center at New York's Idlewild Airport, which opened in 1962, provided TWA with a stylish and iconic terminal, cementing the airline's reputation as one of the great airlines of the early Jet Age.

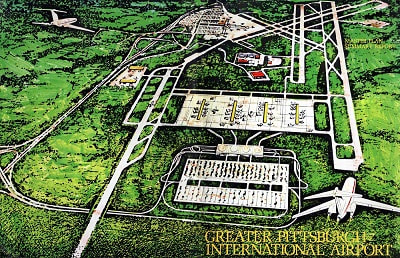

People will be less familiar with TWA's USD 13.7-million proposed expansion of the West Dock at Greater Pittsburgh Airport. Presented in March 1966, the revolutionary concept would bring cars and airplanes within 40 paces of each other. The bi-level oval-shaped facility, to be linked to the existing central airport terminal, would have provided a dozen gates capable of accommodating up to 16 TWA jetliners. The upper level would have housed 12 ticket and check-in lounges for departing passengers. Baggage delivery to arriving passengers would be on the lower level. Both levels would have been served by four-lane, one-way roadways and one above the other, circling the inner rim of the facility.

Own this fantastic image and other PIT items!

Including a free article from TWA's Skyliner Magazine about the terminal proposal!

WHY TWA'S PLAN DIDN'T FLY

However revolutionary, airport experts didn't care much for TWA's idea. Airport aviation consultants Landrum & Brown were quick to point out several critical design factors that were overlooked in TWA's proposal, the most important one being that the terminal could not be expanded. Also, the proposed plan would have only created a net gain of eight aircraft gates, bringing the total to 33, far below the airlines' request of 40-43 gates by 1970. Lastly, the needed two-way aircraft taxiway clearance, imperative because of the ramp activity in this area, was not provided. Finally, it was decided to build a conventional pier instead. The West Dock opened in 1973.

What do you think of the design? Would it have been efficient and effective? Leave your comments below!

More airport articles: Click here

Want more stunning airport photos & stories

Sign up to newsletter below to know when new content goes online

1 Comment

Nuestros fans de Sudamérica nos envían con frecuencia mensajes en los que nos critican por descuidar los aeropuertos de su hermoso y sorprendente continente. Tienen razón, por supuesto, y hoy, ¡vamos a empezar a corregir el registro!

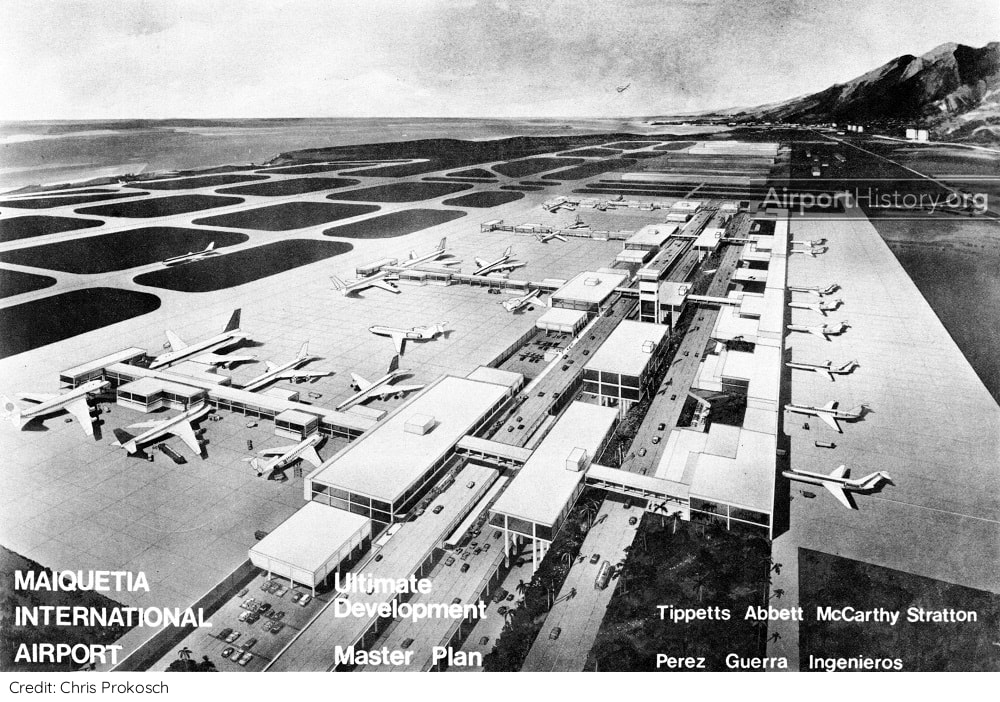

En lo más profundo de la bóveda de AirportHistory.org, hemos encontrado recientemente el Plan Maestro de 1969 del Aeropuerto Internacional de Maiquetía "Simón Bolívar", la principal puerta de entrada internacional de Venezuela. A mediados del siglo XX, Venezuela era un país petrolero en auge. Con el rápido crecimiento del transporte aéreo y la abundancia de dinero, el gobierno planificó un enorme proyecto de expansión, que sólo se ejecutó parcialmente. ¿Tiene curiosidad por saber lo que los planificadores tenían originalmente en mente para el futuro de Maiquetía? Sin más preámbulos, ¡echemos un vistazo!

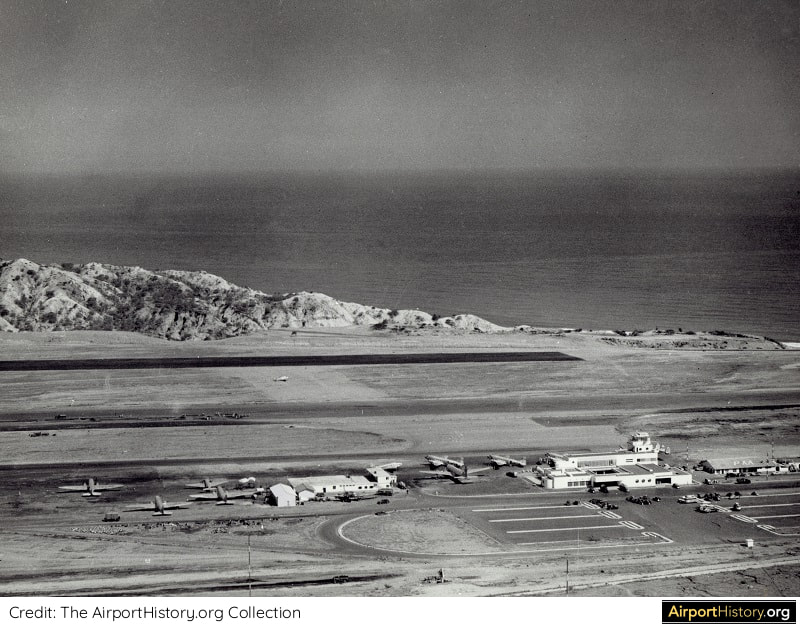

UNA BREVE HISTORIA

Conocido originalmente como Aeropuerto de La Guaira, el aeropuerto fue construido en 1930 por Pan American Airways. Para 1949, contaba con una pista de 1.524 metros, que posteriormente se amplió a 3.000 metros. El edificio original de la terminal, hacia el extremo oriental del aeropuerto, se inauguró en 1948. Esta vista aérea de 1948 de lo que entonces se llamaba Aeropuerto de La Guaira, muestra la pintoresca ubicación del aeropuerto en la orilla del mar.

PLAN MAESTRO

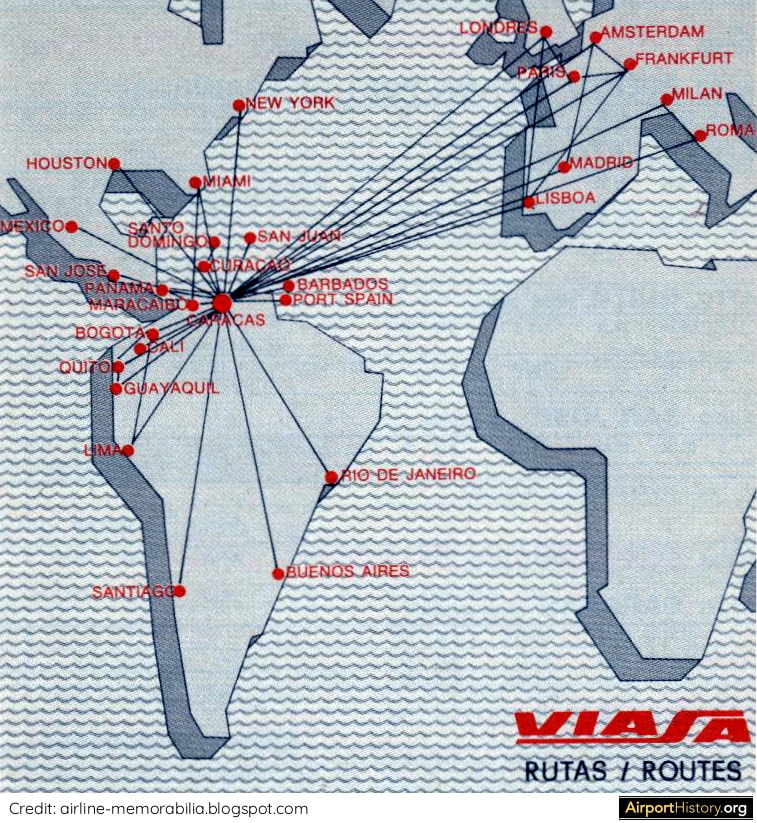

En 1970, Maiquetía atendía a 1,47 millones de pasajeros, lo que lo convertía en el tercer aeropuerto más activo de Sudamérica, después de los aeropuertos de Bogotá-El Dorado y São Paulo-Congonhas. Desde su fundación en 1960, VIASA, la aerolínea nacional de Venezuela, se había convertido rápidamente en una de las principales compañías aéreas de Sudamérica, conectando ciudades de Sudamérica, Norteamérica y Europa. La aerolínea necesitaba un aeropuerto de origen que pudiera acomodar sus ambiciones de crecimiento. En 1968, el gobierno contrató los servicios de la renombrada firma Tibbetts-Abbott-McCarthy--Stratton (TAMS) para preparar los planes para el futuro desarrollo de Maiquetía.

¿Sabías que?

Uno de los expertos encargados del proyecto del Plan Maestro de Maiquetía fue Walther Prokosch, el arquitecto que dirigió el diseño de la terminal de Pan Am en el aeropuerto JFK y el Plan Maestro del aeropuerto DFW.

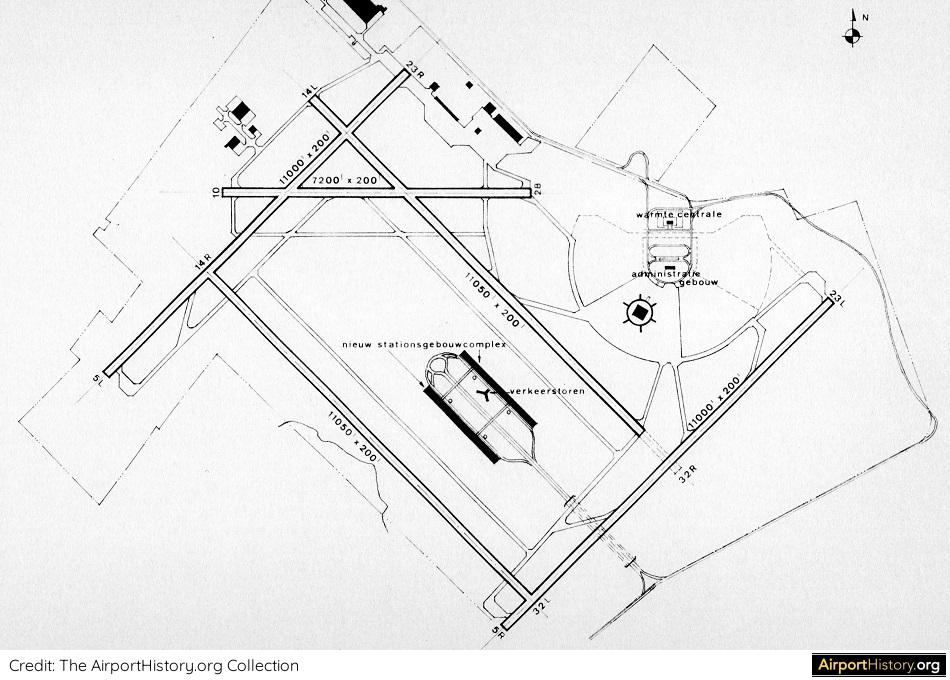

NUEVAS PISTAS

Los estudios de tráfico preveían que Maiquetía manejaría 30 millones de pasajeros en el año 2000, 20 veces más que en 1970, por lo que se requería una ampliación radical del aeropuerto. Los planificadores previeron una ampliación a gran escala del aeropuerto hacia el oeste con dos nuevas pistas y un nuevo complejo de terminales de pasajeros. En primer lugar, se construiría una nueva pista 09/27 de 11.483 pies (3.500 metros) entre la pista original 08/26 y el mar. Su construcción implicaría el movimiento de 650 millones de pies cúbicos de tierra. La pista se puso en marcha en 1975. Más adelante, se construiría una segunda pista de 215 metros al norte y al oeste de la pista 09/27. Tendría una pista de rodaje de longitud completa y su construcción implicaría la eliminación de una serie de colinas junto a la orilla. La pista debía estar terminada a principios de los años 80, tras lo cual probablemente se cerraría la pista original 08/26.

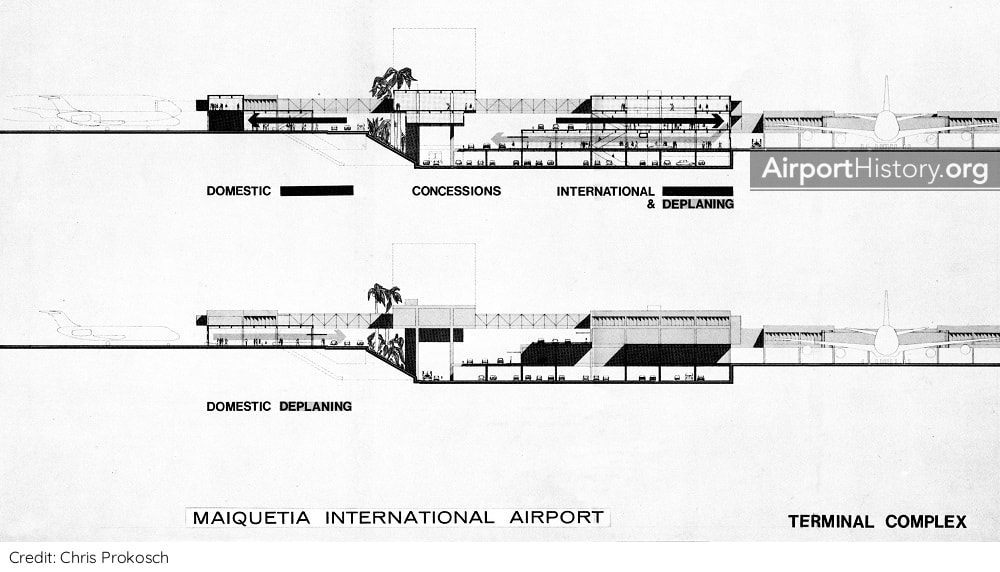

TERMINALES

En los planos de distribución definitivos, los planificadores prevén una serie de edificios terminales de pasajeros construidos a lo largo de una carretera principal. Al norte habría cuatro módulos terminales para los vuelos internacionales. En el lado sur, el de la montaña, habría un edificio terminal alargado para los vuelos nacionales. En total, habría 48 puertas servidas por puentes de embarque de pasajeros : 24 puertas internacionales y 24 puertas nacionales. Los lados internacional y doméstico estarían conectados por edificios en la mediana de la carretera dorsal, que contendría espacios comerciales. Habría espacio para el estacionamiento de 2800 automóviles. El complejo era demasiado pequeño para justificar una plataforma automatizada de transporte de personas, pero se dejó espacio en el diseño para construirla eventualmente si fuera necesario.

¿Quiere más fotos e historias impresionantes de aeropuertos?

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín de noticias para saber cuándo se publican nuevos contenidos.

DESARROLLO POR FASES

En un principio, todo el desarrollo tendría lugar en el lado norte, con terminales de pasajeros separadas para el tráfico internacional y nacional, que se inauguraron en 1978 y 1983 respectivamente. Las terminales contaban con vestíbulos de embarque a lo largo de la terminal. Más adelante sería posible añadir muelles perpendiculares, aumentando el número de puestos de contacto. En este momento, no está claro si se mantuvo la idea de una terminal doméstica sur a largo plazo o si se eliminó del Plan Maestro desde el principio. ¡Déjenos un comentario abajo si sabe la respuesta!

CRECIMIENTO MÁS LENTO

A lo largo de las décadas, el crecimiento del tráfico fue mucho más lento de lo previsto. Nunca se alcanzaron los 30 millones de pasajeros que se habían proyectado a finales de los años 60. El récord se sitúa en 12,18 millones de pasajeros en 2013, tras lo cual la economía entró en caída libre. Como consecuencia, el Plan Maestro solo se aplicó parcialmente. La pista paralela 09/27 nunca se construyó. Tampoco se añadieron terminales de pasajeros adicionales. En cambio, a principios de la década de 2000, se amplió y remodeló la terminal internacional existente. La terminal nacional no se ha modificado, sólo se ha dotado de nuevos puentes de embarque acristalados.

Una imagen aérea de la terminal internacional tomada tras la ampliación y remodelación de principios de la década de 2000. El edificio de la administración del aeropuerto y la terminal doméstica son visibles en el fondo. Obsérvese también la construcción en la explanada de la terminal. Iba a ser un hotel de aeropuerto, pero nunca se terminó.

El Plan Maestro de Maiquetía de 1968 es el testimonio de una época en la que el cielo era literalmente el límite para Venezuela. ¡Esperemos que estos tiempos vuelvan algún día!

¿Qué opina de los planes originales para Maiquetía? Háganoslo saber en los comentarios más abajo.

Este artículo ha sido traducido por Gianfranco Perticara. Puede encontrar la versión en inglés aquí. For the English version, click here.

¿Quiere más fotos e historias impresionantes de aeropuertos?

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín de noticias para saber cuándo se publican nuevos contenidos.

Para la versión en español, haga clic aquí

Our fans in South America frequently send us messages requesting we don't neglect the airports on their beautiful and amazing continent. They are right of course, and today we will start correcting the record!

Deep in the AirportHistory.org vault, we recently found the 1969 Master Plan for Maiquetía "Simón Bolívar" International Airport, the main international gateway for Venezuela. In the mid-20th century, Venezuela was a booming oil country. With air travel rapidly growing and money being plentiful, the government planned for a huge expansion project, which was only partially implemented. Curious about what the planners originally had in mind for the future of Maiquetía? Without further ado, let's take a look!

A SHORT HISTORY

Known originally as La Guaira Airport, the airport was constructed in 1930 by Pan American Airways. By 1949, it had a 5,000-foot (1,524-meter) runway, which was later extended to 9,842 feet (3,000 meters). The original terminal building, toward the eastern end of the airport, was opened in 1948.

MASTER PLAN

By 1970, Maiquetía was handling 1.47 million passengers, making it the third busiest airport in South America, after Bogota El Dorado and São Paulo Congonas airports. Since its founding in 1960, VIASA, Venezuela's national airline, had quickly developed into of South America's premier airlines, connecting cities in South America, North America, and Europe. The airline needed a home airport that could accomodate its growth ambitions. In 1968, the government engaged the services of the renowned firm Tibbetts, Abbott, McCarthy, and Stratton (TAMS) to prepare plans for Maiquetía's future development.

Did you know?

One of the experts in charge of the Maiquetía Master Plan Project was Walther Prokosch, the architect who led the design of the legendary Pan Am terminal at JFK Airport and the Master Plan for DFW Airport.

NEW RUNWAYS

Traffic studies projected that Maiquetía would handle 30 million passengers by the year 2000, 20 times more than in 1970, thus requiring a radical expansion of the airport. Planners envisaged a large-scale expansion of the airport to the west with two new runways and a new passenger terminal complex. First, a new 11,483-foot (3,500-meter) runway 09/27 would be built between the original runway 08/26 and the sea. Its consctruction would involve moving 650 million cubic feet of earth. The runway was commissioned in 1975. Later on, a second runway would be built 705 feet (215 meters) to the north and west of runway 09/27. It would have a full length taxiway and its construction would involve the removal of a series of hills beside the shore. The runway was to be completed in the early 1980s, after which the original runway 08/26 would likely be closed.

TERMINALS

In the ultimate layout, planners envisaged a series of passenger terminal buildings built along a spine road. To the north would be four terminal modules handling international flights. On the south side--the mountain side--would be an elongated terminal building handling domestic flights. A total of 48 gates served by passenger boarding bridges would be provided: 24 international gates and 24 domestic gates. The international and domestic sides would be connected by buildings in the median of the spine road, which contained concessions. There would be parking space for 2,800 cars. The complex was too small to justify an automated people mover shuttle but space was left in the design to construct one eventually if needed.

Want more stunning airport photos & stories?

Sign up to our newsletter below to know when new content goes online.

PHASED DEVELOPMENT

Initially, all development would take place on the north side with separate passenger terminals for international and domestic traffic, These opened in 1978 and 1983 respectively. The terminals had boarding concourses running along the length of the terminal. Later on, perpendicular pier could be added, increasing the number of contact stands. At this point, it is unclear if the idea of a south domestic terminal in the long run was retained or if it was dropped from the Master Plan early on. Leave us a comment below if you know the answer!

SLOWER GROWTH

Over the decades, traffic growth was much slower than anticipated. The traffic of 30 million passengers, which had been projected in the late 1960s, was never reached. The record stands at 12.18 million passengers in 2013, after which the economy went into free fall. As a result, the Master Plan was only partially implemented. The parallel runway 09/27 was never built. Also, no additional passenger terminals were added. Instead, in the early 2000s, the existing international terminal was enlarged and re-modelled. The domestic terminal has not been altered, only having been outfitted with new glass-cladded boarding bridges.

The 1968 Maiquetía Master Plan stands testament to a time when the sky was literally the limit for Venezuela. Let's hope these times will return one day!

What are your thoughts on the original plans for Maiquetía? Let us know in the comments below!

More airport articles: click here

Want more stunning airport photos & stories?

Sign up to our newsletter below to know when new content goes online.

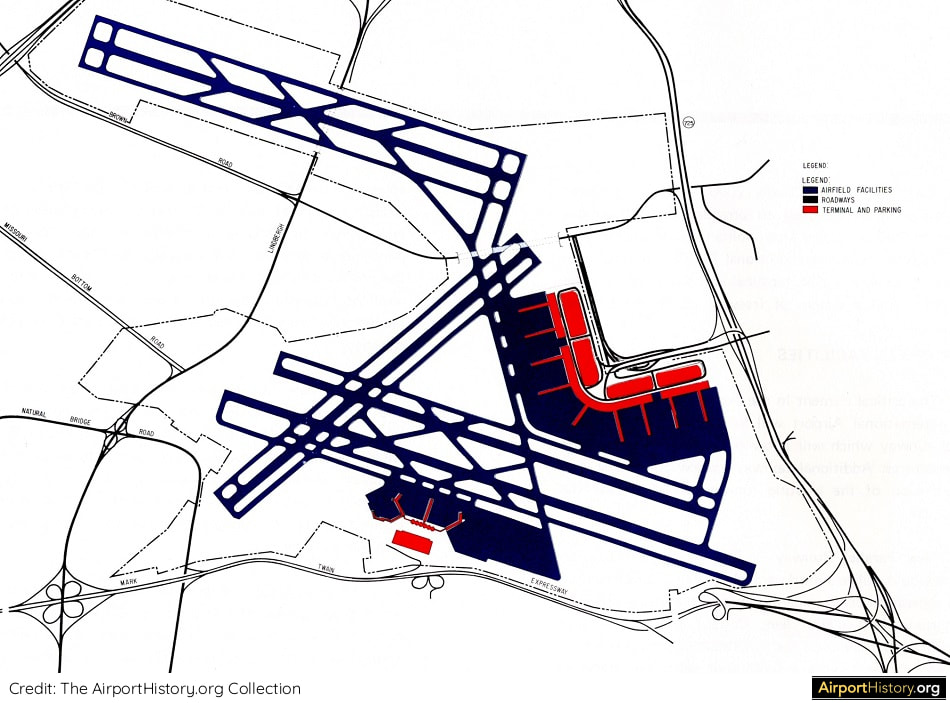

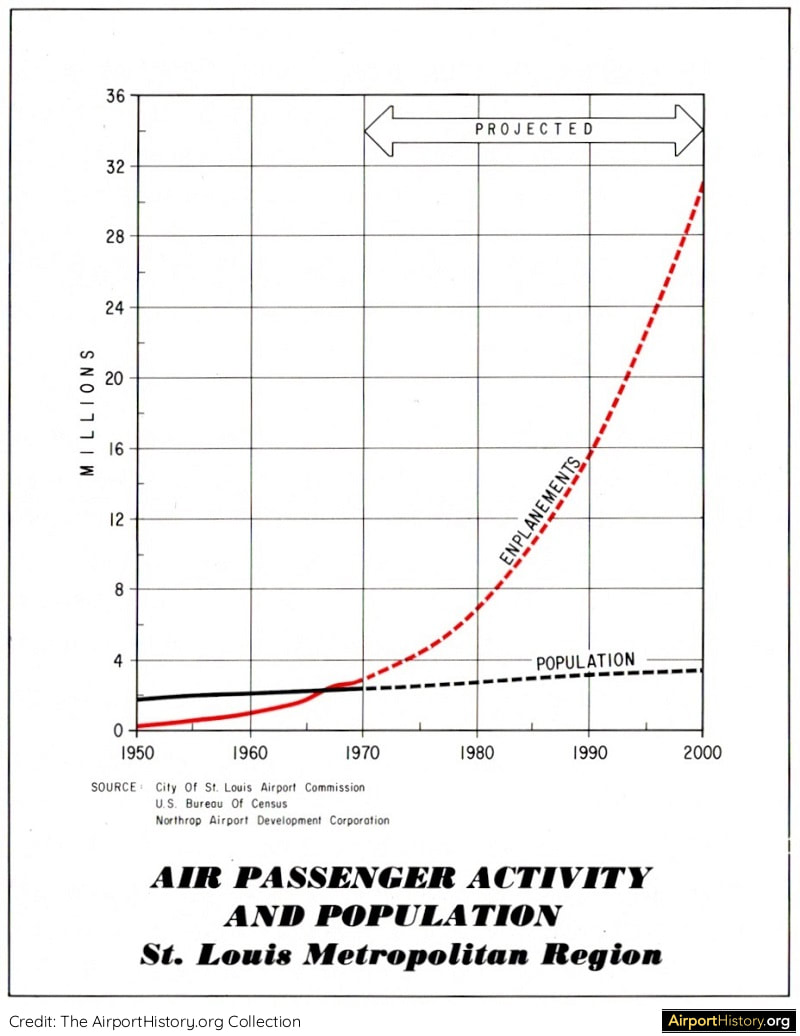

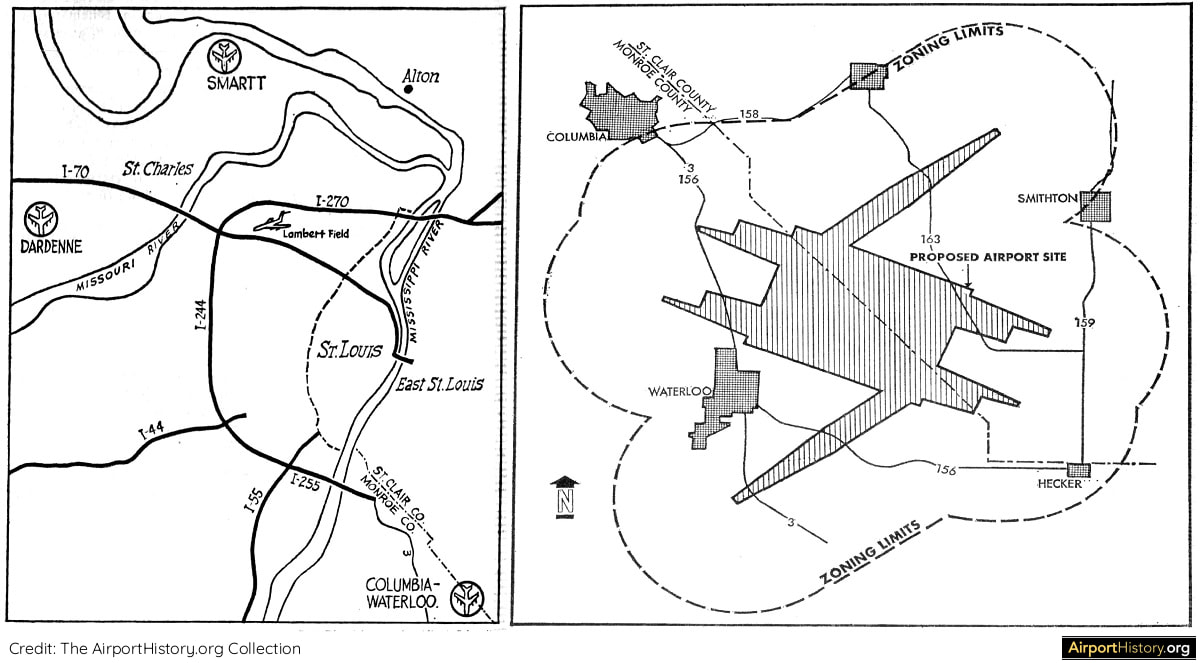

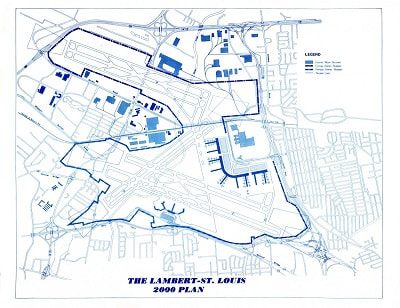

During our recent digs in the AirportHistory.org archives we unearthed a fascinating 1972 proposal to massively expand St. Louis Lambert International Airport.

The plan, called the Lambert-St. Louis 2000 Plan envisaged the construction of a third parallel runway and a huge new terminal complex north of the current airport. Let's take a closer look and see what this plan was all about!

BACKGROUND

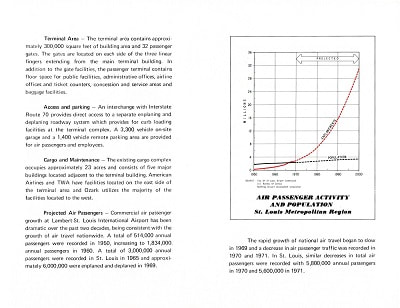

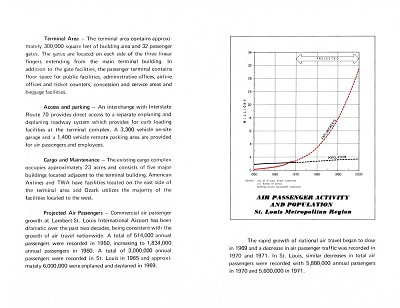

The Jet-Age travel boom led to an ongoing capacity crisis at St. Louis Lambert International Airport, then called Lambert-St. Louis International Airport. Between 1958 and 1969, the airport's passenger traffic increased almost fourfold. By 1970, Lambert handled 6.6 million passengers, ranking it the 13th busiest in the nation and 20th in the world.

Despite a planned terminal expansion, in 1968, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) concluded that Lambert would be unable to accomodate the air traffic demands expected by 1982 and that a replacement airport should be made operational by 1980.

Want more stunning airport photos & stories?

Sign up to our newsletter below to know when new content goes online.

THE COLUMBIA-WATERLOO PLAN

In May 1972, the newly created St. Louis Metropolitan Area Airport Authority, adopted a plan prepared by R. Dixon Speas Associates for a proposed USD 350 million airport to be located near Columbia and Waterloo, 19 miles (30 kilometers) southeast of St. Louis, in the neighboring state of Illinois. In January 1972, the authority applied for USD 8.4 million to begin land acquisition.

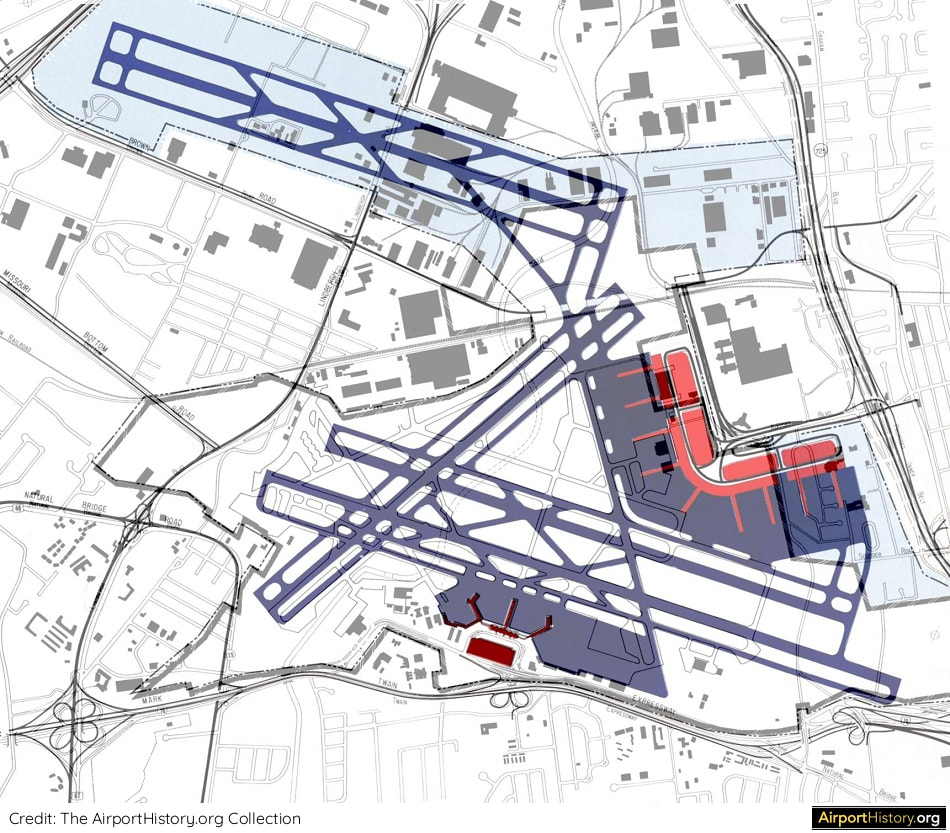

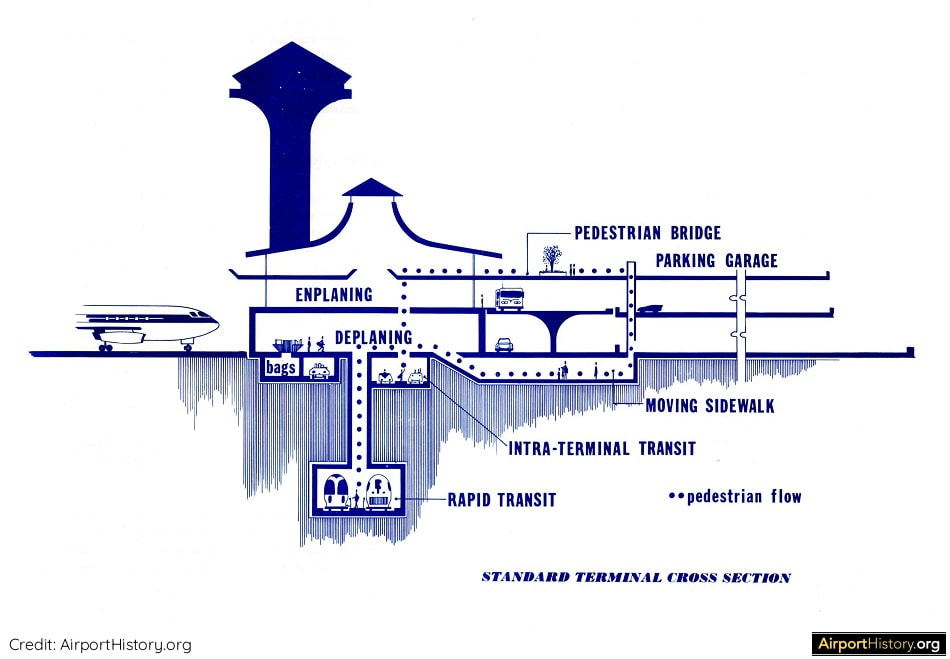

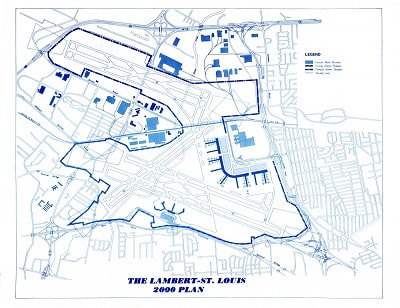

THE LAMBERT-ST. LOUIS 2000 PLAN

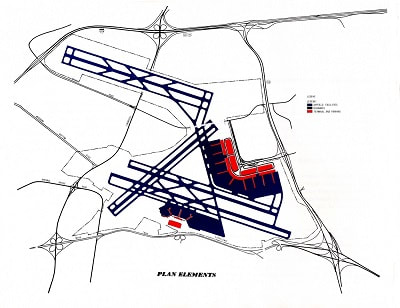

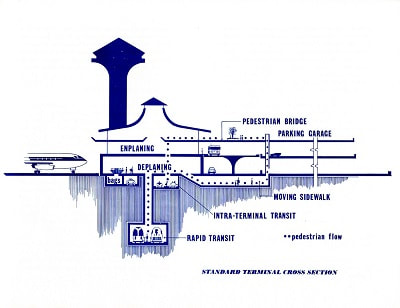

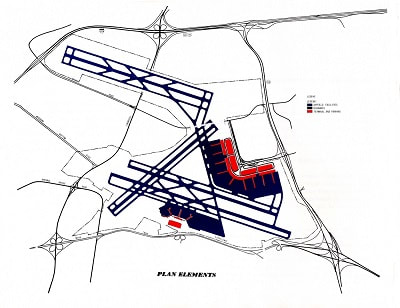

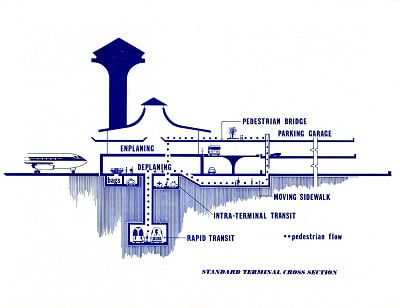

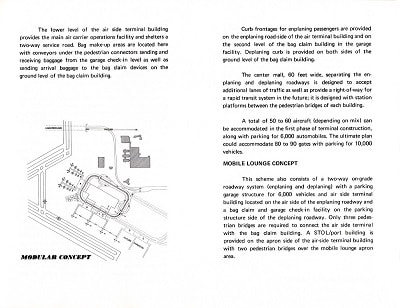

There was fierce opposition to the plans, among others by the Missouri legislature. It created the Missouri-St. Louis Metropolitan Airport Authority to oppose the Illinois airport plan. In October 1972, the authority unveiled an expansion plan titled the Lambert-St. Louis 2000 Plan, designed to enable Lambert to adequately serve the city's needs until the year 2000. The plan, developed by Wilbur Smith & Associates, called for adding 800 acres to the airport, building a new parallel northwest-southeast runway north of the McDonnell Douglas facilities at Lambert and constructing a new ninety-gate terminal building on the northeast side of the airport.

The Lambert-St. Louis 2000 Plan carried a USD 370-million price tag, including USD 75 million for land acquisition, USD 75 million for the new terminal, and USD 30 million for the new runway and taxiways.

The runway would provide the FAA-required spacing to permit simultaneous instrument landings, which Lambert's configuration did not allow. Improvements under the plan would allow Lambert to handle 60 million passengers annually. SUPPORT The plan contains many letters of support, including from: US, state, and local officials; Ozark Airlines, which had its headquarters in St. Louis; Ford, which had a major assembly plant north of the airport; and the Norfolk and Western Railway Company, which was active in developing industry in the vicinity of the airport. Interestingly, the plan didn't contain endorsements from Trans World Airlines (TWA), which had a major base at St. Louis-Lambert, and from the McDonnell Douglas Corporation, a major aerospace manufacturing firm and defense contractor, which was headquartered at the airport and had sprawling facilities there.

Add the Lambert-St. Louis 2000 Master Plan to your airport collection!

Click the images below to purchase a high-quality digitized copy of this visionairy 62-page plan, a must-have for airport history fans!

During a referendum and subsequent mayoral election in March 1973, support for the Victoria-Waterloo proposal was swept away. The focus shifted back to improving Lambert. Things were looking good for the Lambert-St. Louis 2000 plan.

However, a significant obstacle arose when James S. McDonnell, chairman of McDonnell Douglas, criticized the plans on the grounds that it would wipe out some of the company's facilities and inhibit its future expansion at the site. As a result, new master plan studies were prepared. Due to the oil crisis of 1973 and the resulting decline in traffic, the plans focused on increasing capacity of the existing terminal. There was no provision for an additional runway, as improvements to the existing runway system were deemed sufficient to handle traffic growth into the mid-1990s.

DECLINE

In 2000, Lambert handled a record 30.5 million passengers, ranking it the eighth busiest airport in the United States. That same year the decision was taken to build a new runway 11-29 west of the airport. It was half the number of passengers once projected by the Lambert-St. Louis 2000 Plan back in 1972 and it was to be the highest number of passengers that Lambert would ever process. Following the absorption of TWA into American Airlines in 2001 and the subsequent termination of TWA's St. Louis hub, traffic dwindled from 26 million passengers in 2001 to 13 million in 2004. In 2019, the last year before COVID, Lambert handled almost 16 million passengers.

The Lambert-St. Louis 2000 Plan stands as a testament to a time when the sky was literally the limit and St. Louis-Lambert was poised to become one of busiest hubs in the US and one of the world's pre-eminent gateways!

What do you think of the Lambert-St. Louis 2000 Plan? Do you think it could have meant a better future for St. Louis-Lambert Airport or would things have turned out more or less the same way?

Let us know your thoughts in the comments below!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS & FURTHER RECOMMENDED READING

For this article, I quoted from the book The Aerial Crossroads of America: St. Louis Lambert Airport, written by Daniel Rust. Published by the Missouri History Museum Press in 2016, this 336-page book is a scholarly, exhaustive history on Lambert International Airport up until 2015. My only major criticism on the book is that there are very few illustrations, which is a missed opportunity. Still, Aerial Crossroads is a fine book and I highly recommend it. Buy your copy from the University of Chicago Press or from Amazon. Also, check out the avaiable STL publications in the AirportHistory library.

Add the Lambert-St. Louis 2000 Master Plan to your airport collection!

Click the images below to purchase a high-quality digitized copy of this visionairy 62-page plan, a must-have for airport history fans!

The AirportHistory.org archives contain many of the original master plans for airports like DFW, AMS, JFK, LHR, CDG, LAX, ORD and many, many more.

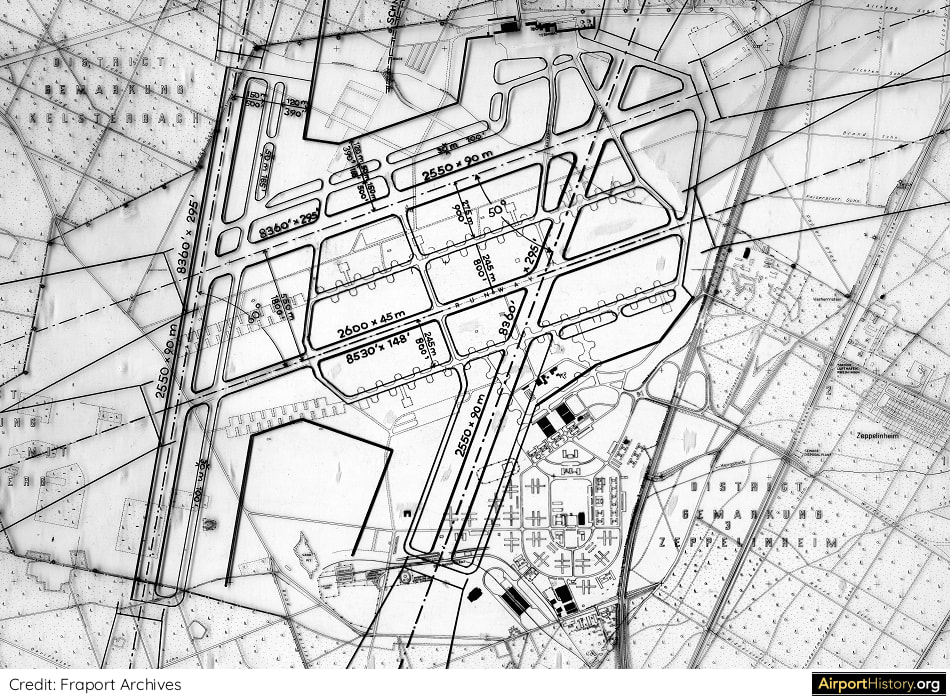

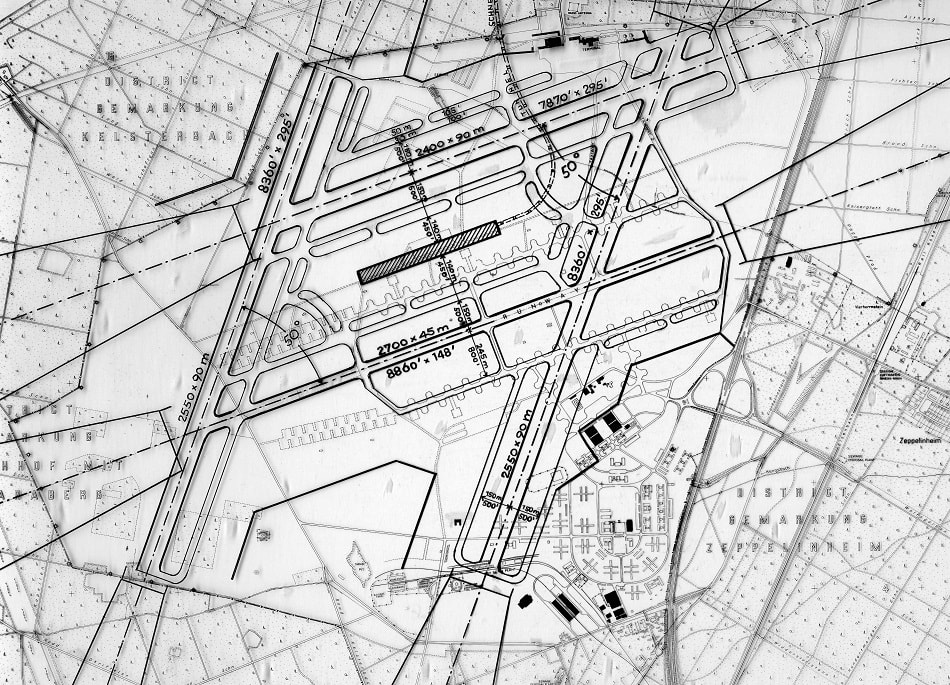

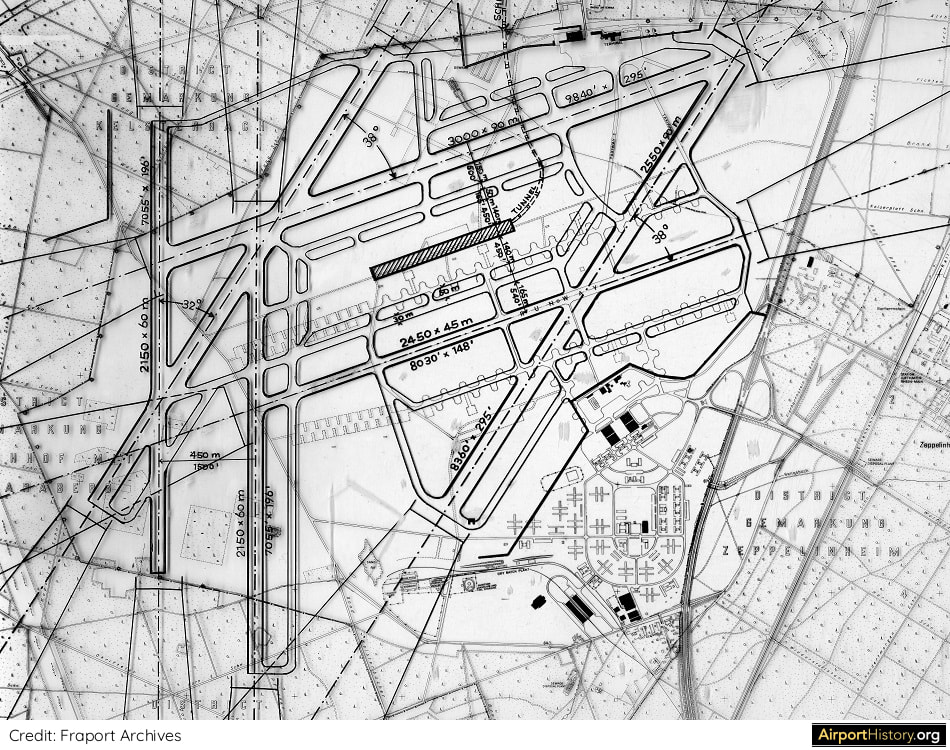

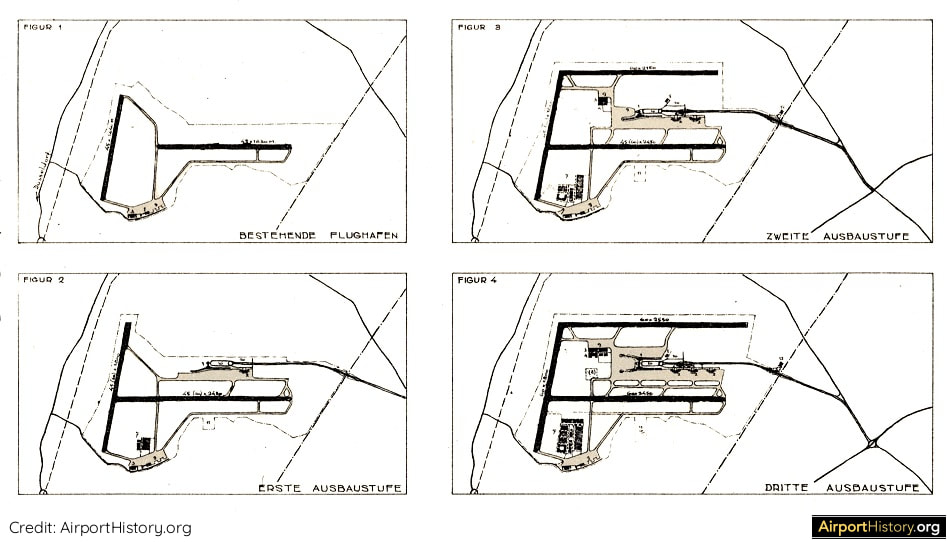

They show us how planners of decades past saw the future of aviation. They truly make for fascinating reading. Today, we will look at how the planners of Frankfurt Airport envisaged the airport's future back in the late 1940s and 1950s. Some of the development alternatives contain up to six runways and depict some very forward-looking concepts like a linear midfield terminal. Let's have a look!

An aerial view of Frankfurt in 1949 looking east. The first runway (right in picture) was built by the US Army in the summer of 1945. On December 22, 1949, the second parallel runway, shown here at the time of completion, was put into use.

That same year, the US Army transferred the operation of the northern part of the airport to the 'Verkehrsaktiengesellschaft Rhein-Main' (VAG), which would later on become Fraport.

In this proposed four-runway layout two additional north-south runways are added, including a proposed predecessor of Runway 18/36 "Startbahn West."

This way, the airport would always have two runways aligned with the prevailing winds, an important consideration at the time.

This plan boasts a total of five runways. This layout would have very much constricted development of the passenger terminal and other facilities later on. It's a good thing Frankfurt wasn't expanded this way!

Want more stunning airport photos & stories?

Sign up to our newsletter below to know when new content goes online!

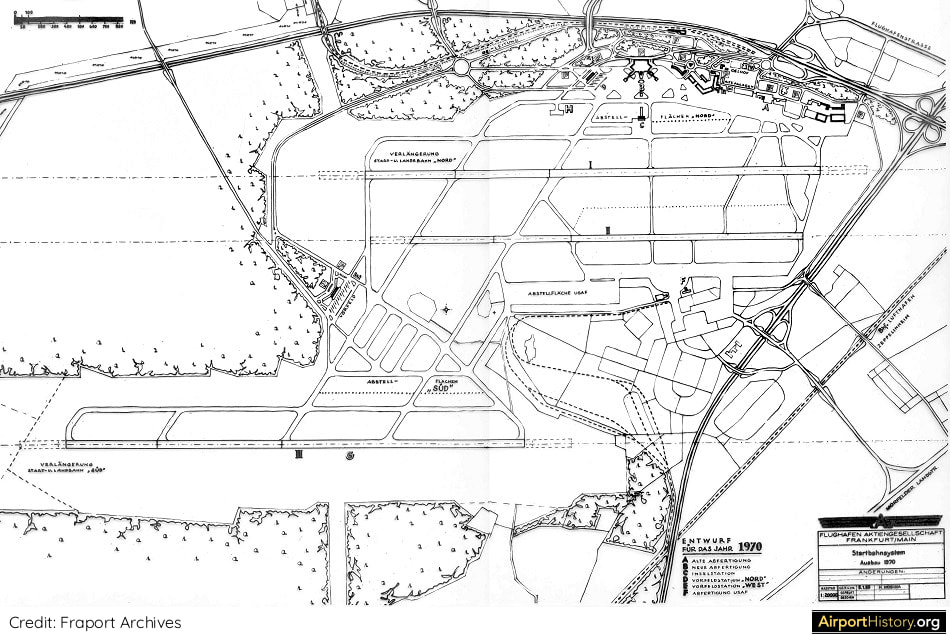

Now it gets interesting! This layout shows a linear midfield passenger terminal (shaded in black), a very advanced concept for the time. The terminal would be directly connected to the local railway system.

At the time, a very similar idea was proposed for the development of nearby Düsseldorf Airport. However, what the planners had in mind was not a modern boarding concourse as we know them today (see next photo).

A careful read of the 1948 Master Plan reveals that the terminal was to have overhanging roofs, underneath which aircraft could park.

The concept was modeled on "the mother of all airports," Berlin Tempelhof, pictured above. Later on the concept was also used at the Pan Am terminal.

This proposed layout boasted a total of six runways in the shape of three sets of parallel runways.

Like this article?

Please consider supporting us with a simple donation!

Your support will help us protect & preserve the heritage of the world's great airports!

This proposed layout, produced in the 1950s, shows a third parallel runway, built to the south of the airport and to be completed by 1970. A similar plan would resurface in the 1990s when Frankfurt was planning its fourth runway.

This plan, prepared in the late 1950s at the dawn of the Jet Age, shows Startbahn West, basically as it would be built decades later.

Built at 13,123 feet (4,000 meters), runway 18/36 is a long runway. But this plan mentions that the runway could reach a length of up to 16,400 feet (5,000 meters), something which likely can be explained by the airport's function as a strategic NATO airbase at the time.

What do you think? Would Fraport have been better off if it had expanded according to one of the proposed layouts above? Share your thoughts on the plans in the comments below!

More airport articles: See landing page

Like this article?

Please consider supporting us with a simple donation!

Your support will help us protect & preserve the heritage of the world's great airports!

Did you know Düsseldorf Airport's first modern Master Plan envisaged up to six runways? Read all about it below!

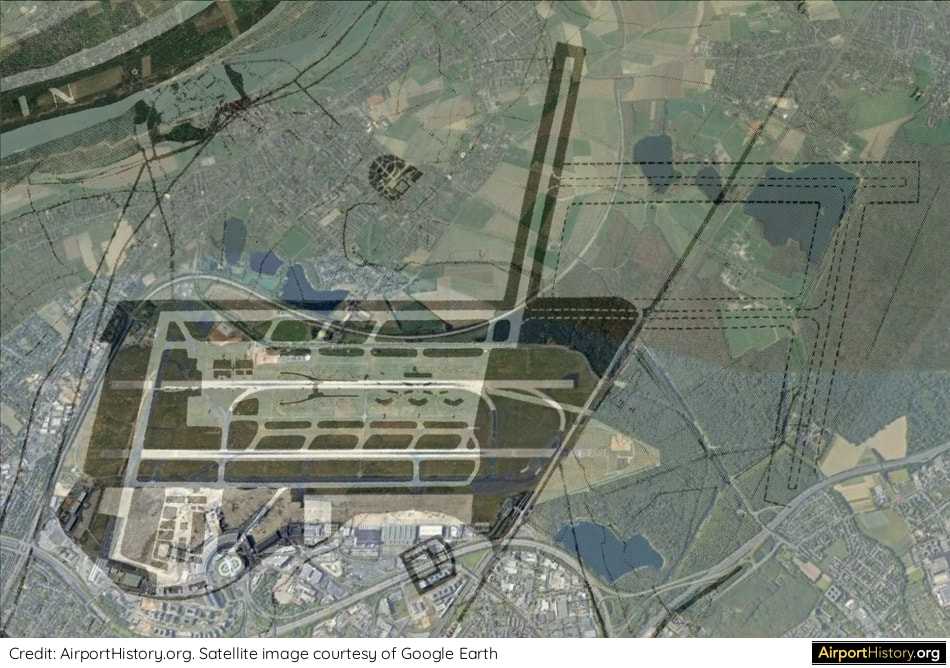

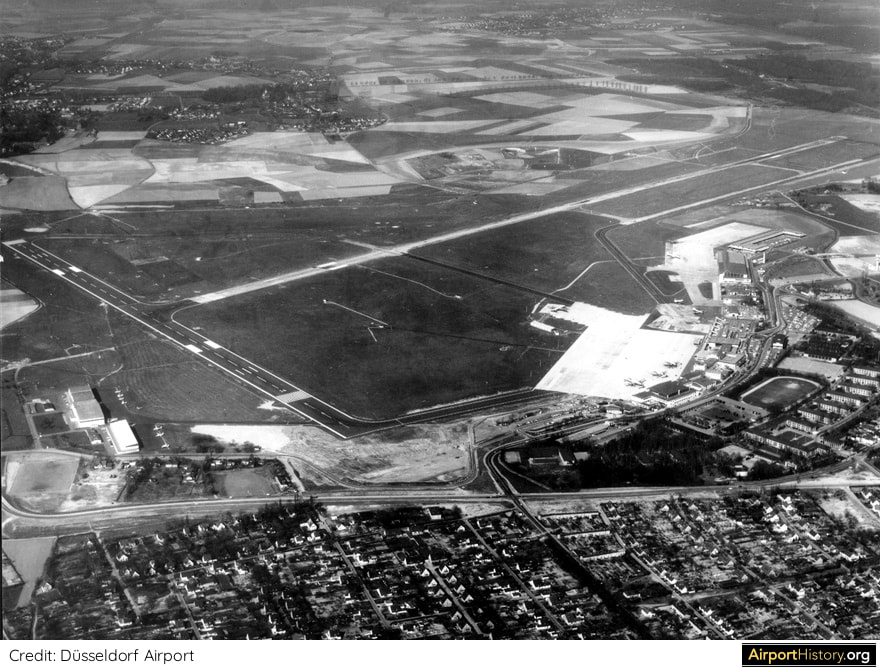

Düsseldorf International Airport is Germany's third busiest airport after Frankfurt and Munich. In 2019, the airport handled over 25 million passengers. Despite having a larger catchment area than Frankfurt and Munich, the airport's development potential has been limited. Düsseldorf has two parallel runways. However, the runways are close to each other and cannot be used independently. In addition, use of the parallel runway is capped due to political restrictions. Things could have looked very much different...

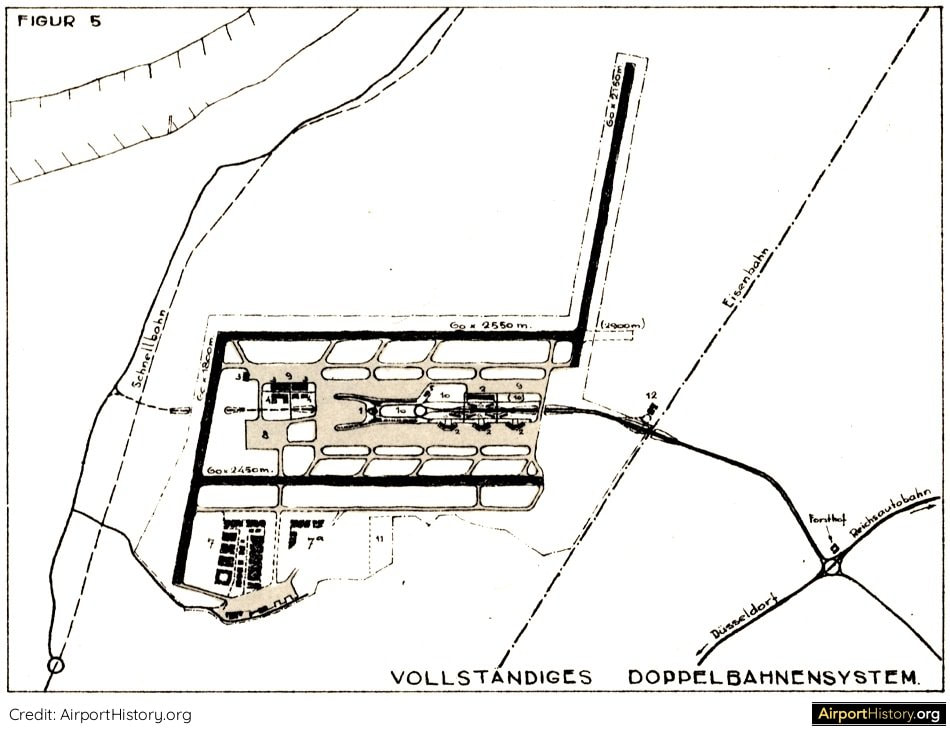

A MIDFIELD TERMINAL COMPLEX

In 1952, two years after Düsseldorf Airport had been returned to civil authorities, the airport asked NACO Netherlands Airport Consultants B.V. to prepare a Master Plan for the airport's long-term development. As shown in the images below, NACO envisaged that an entirely new passenger terminal complex would be built north of the main runway. Later on, a new independent parallel runway would be built, putting the new passenger terminal at the heart of the airport.

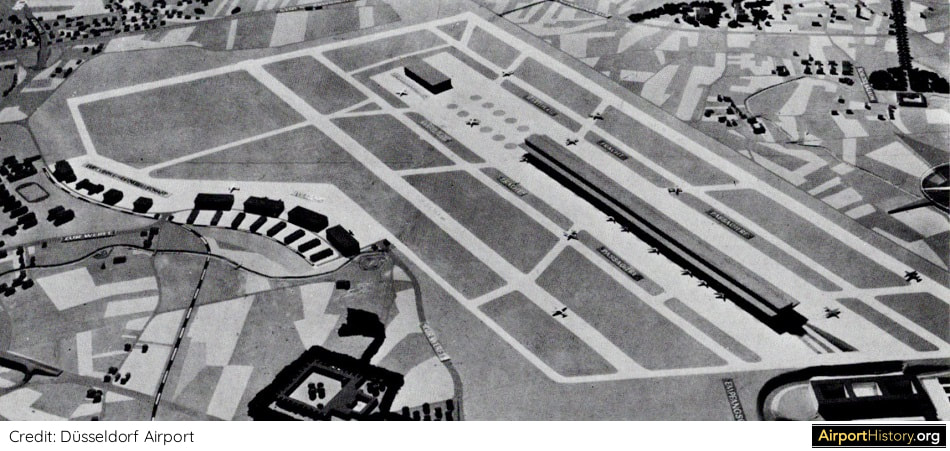

The above artist's impression shows a possible layout of the midfield terminal, indicating a linear mile-long boarding concourse with aircraft parked on either side under an overhead canopy, and what looks like a headhouse or processor located at the bottom left.

The concept is really very contemporary for 1952 and is reminiscent of the once planned Westside Terminal at DFW. The current passenger terminal is located where the four hangars are visible (left).

SIX RUNWAYS

Finally, as shown above, a fourth runway--which somehow looks like Düsseldorf's version of FRA's Startbahn West--would be added, providing the airport with two pairs of parallel runways. But it didn't stop there. As shown below, the plan had a provision to add two more runways, raising the total number of runways to six. One of the main runways could be lengthened to over 15,000 feet (4,500 meters)--an amazing length even now, let alone in the days before jets!

However, instead the airport chose to further develop the south side of the airport.

A second parallel runway opened in 1992 but was built close to the existing runway. In order to get it built concessions had to be made restricting its use.

And the rest as they say is airport history!

What if these plans would have been executed? Could Düsseldorf Airport have played a much more prominent role in Germany and Europe than it does today? We want to hear from our fans and local experts. Leave your comments below! We hope you enjoyed this little blast from the past! There's a LOT more where that came from so make sure you sign up for the newsletter to know when new content goes online!

Want more stunning airport photos and stories?

Sign up to our newsletter to know when new content goes online!

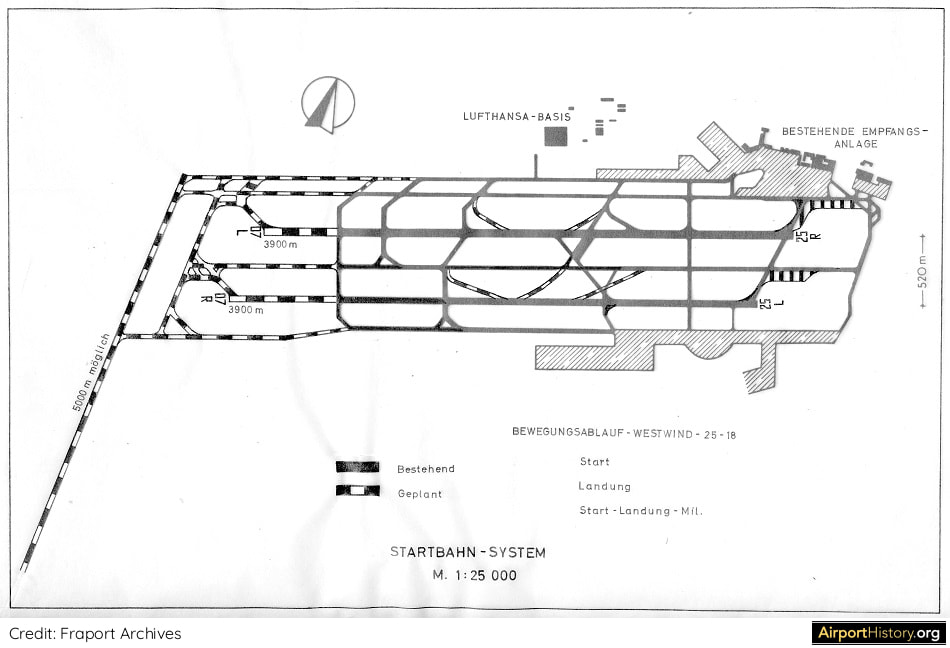

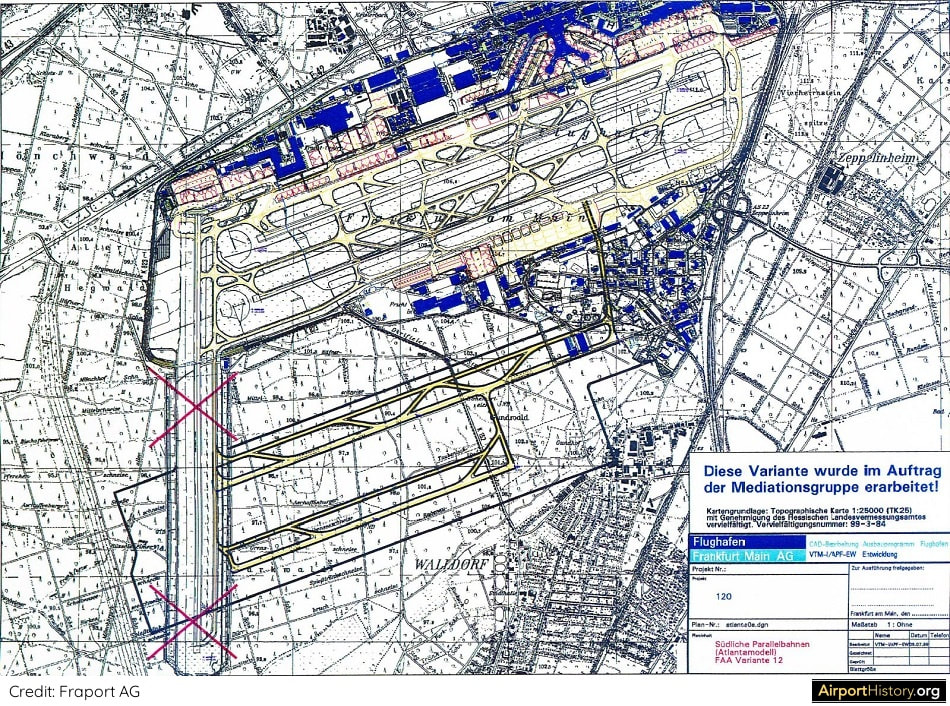

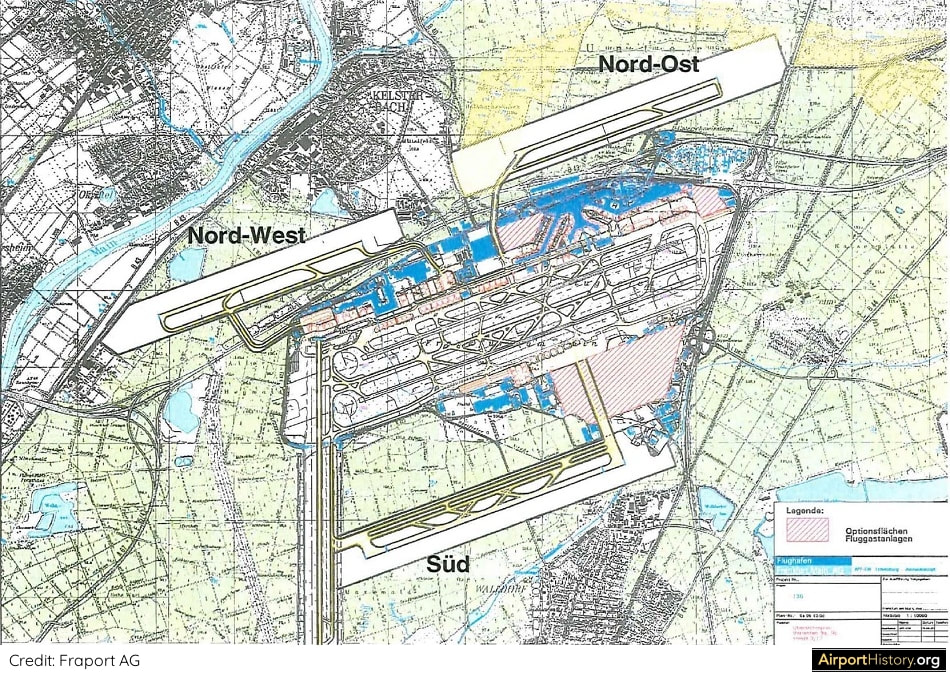

Back in the late 1990s, Frankfurt Airport considered re-configuring its runway system to an Atlanta-style layout with four parallel runways. Read the story behind this plan below!

BACK IN TIME: THE NEED FOR A NEW RUNWAY

The idea of building an additional fourth runway for Frankfurt Airport was first proposed in 1997 by Lufthansa's then-CEO Jürgen Weber. The year prior, Frankfurt had handled over 38 million passengers and 386,000 aircraft movements. The runway layout allowed for 80 movements per hour, translating into about 420,000 annual movements. Thus, the capacity ceiling was in sight. With nearby competitors Amsterdam Schiphol and Paris de Gaulle adding new runways and planning to increase their hourly capacity to a 120 aircraft movements, something needed to be done. A proposed new runway would allow the number of hourly takeoffs and landings to grow by 50% to 120 per hour, translating into over 660,000 annual movements and doubling the number of annual passengers to over 72 million by 2015. Frankfurt's last new runway, the north-south runway named "Startbahn West" (West Runway) had opened in 1984 and became the focus of intense protests by environmentalists, which even lasted three years after the runway had opened.

COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT

With this experience still in mind, the airport decided to closely involve residents of the surrounding communities in the planning process. A pact was made stipulating that the new runway could only be built if it was supported by the majority of nearby residents. Fourteen different variations for increasing runway capacity were studied. The main options involved building a new runway northwest, northeast or south of the airport. Other options were to optimize the current runway system by using new procedures and technologies or by realigning the runway system. Yet another option saw part of traffic being transferred to nearby Erbenheim Airport, a general aviation airport located 9 miles (15 km) west of Frankfurt Airport. The remaining options were different combinations of the above options. THE ATLANTA MODEL The most ambitious option involved building two new east-west oriented runways south of the existing airport, providing the airport with four parallel runways and allowing both simultaneous parallel takeoffs and landings. Under this option, the north-south runway would be closed. The layout was appropriately named the "Atlanta Model". Depending on the mix of aircraft, this layout would allow up to a 150 aircraft movements an hour, as opposed to 120 with most other expansion options. Unsurprisingly, this was the option backed by the home carrier Lufthansa, which operates a global hub out of Frankfurt.

Although never explicitly stated at the time, the Atlanta Model would also have the additional benefit of enabling the airport to do a bit of "land grab", by creating a huge new midfield area, similar to what Schiphol did with the addition of the infamous Polderbaan.

The midfield area--nowadays largely developed with cargo and maintenance facilities--could eventually have been used to develop a large new passenger terminal complex for Lufthansa and its partner carriers.

POLITICAL REALITY

The Atlanta Model was not without its issues. Until the majority of traffic would move to a future midfield terminal, taxiing times to/from the existing terminals would be long and aircraft would have to cross the existing parallel runways, raising the risk of runway incursions. Also, part of the then new Cargo-Sud (Cargo-South) complex would have to be torn down. From a community point of view, the problem with the the Atlanta Model was that it would almost double the airport in size and 600 hectares (1500 acres) of city forest would need be to cut. Also, the number of people affected by aircraft noise would increase by almost half a million. This made the Atlanta Model politically unattainable, and thus, it disappeared off the table. A COMPROMISE Three options remained: the construction of a single new runway north-east, north-west or south of the airport. The conclusion was that a runway north-west of the airport site would have the least impact on local residents and the surrounding environment. The runway's location--north-east of the existing airport and squeezed against the autobahn A3--was quite ingenious in that the layout is extremely compact, thereby barely increasing the airport's footprint. Only a relatively small amount of trees would need to be cut down to build the runway. Also, the amount of additional people affected by noise would be limited to about 225,000.

LANDINGS ONLY

As part of the concessions to get the buy-in from local communities, the runway would be used exclusively for landings, and only aircraft types up to the size of an Airbus A340 would be allowed to use the runway. In December 2007, the plans were approved by the Hessian government (Hesse is the state where Frankfurt is situated) and construction on the runway started in early 2009. In October 2012, after 15 years of discussion, planning and construction, Frankfurt opened the fourth runway, providing the airport with a total of three east-west parallel runways and one north-south runway.

The things that could have been if they had gone with the "Atlanta Model"! What do you think? Let us know your thoughts in the comments below!

Want more stunning airport photos & stories?

Sign up to our newsletter below to know when new content goes online! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to give a special thanks to Markus Grossbach and Annette Schmidt of the Fraport Archive for their help in preparing this article.

After almost 40 years of operation, the TWA Flight Center was closed in October 2001, just before TWA itself ceased to exist (the airline was absorbed into American Airlines).

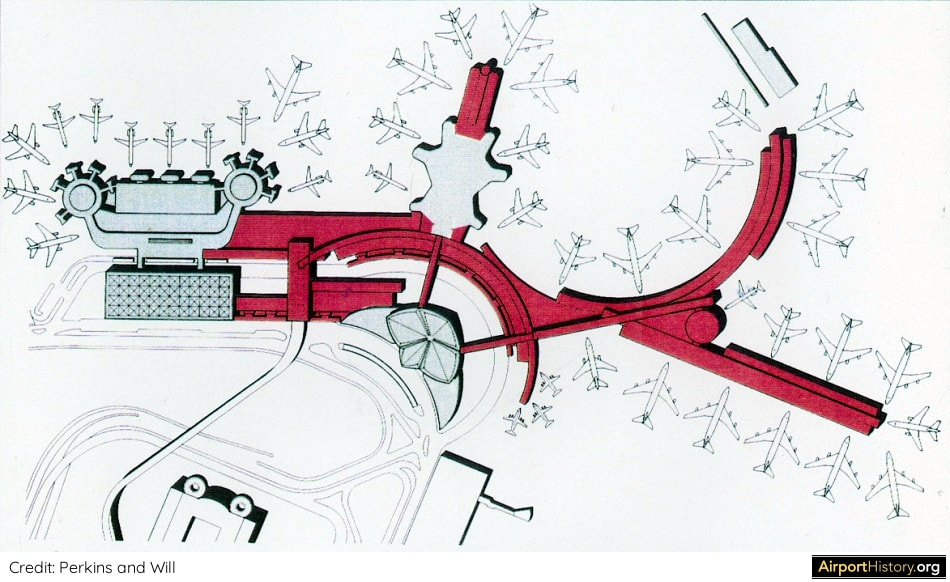

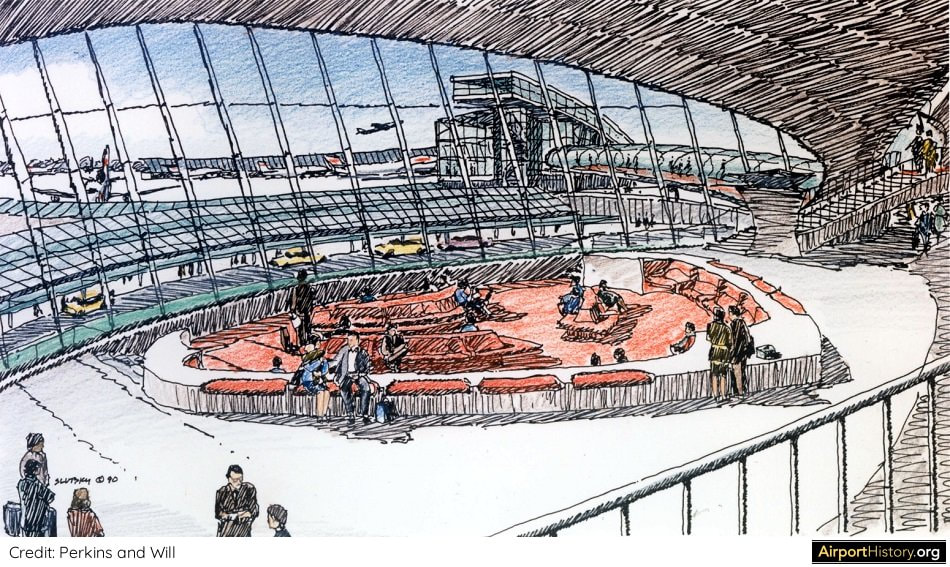

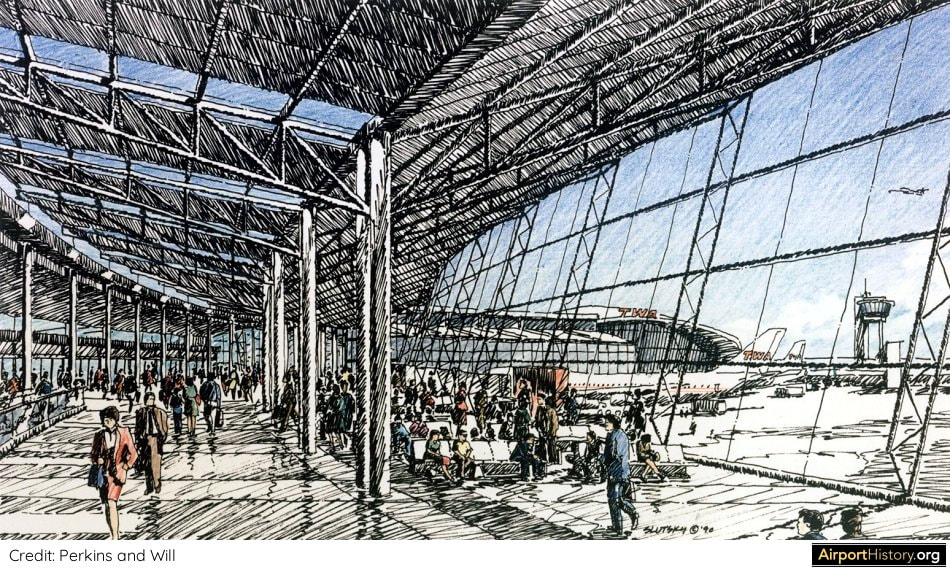

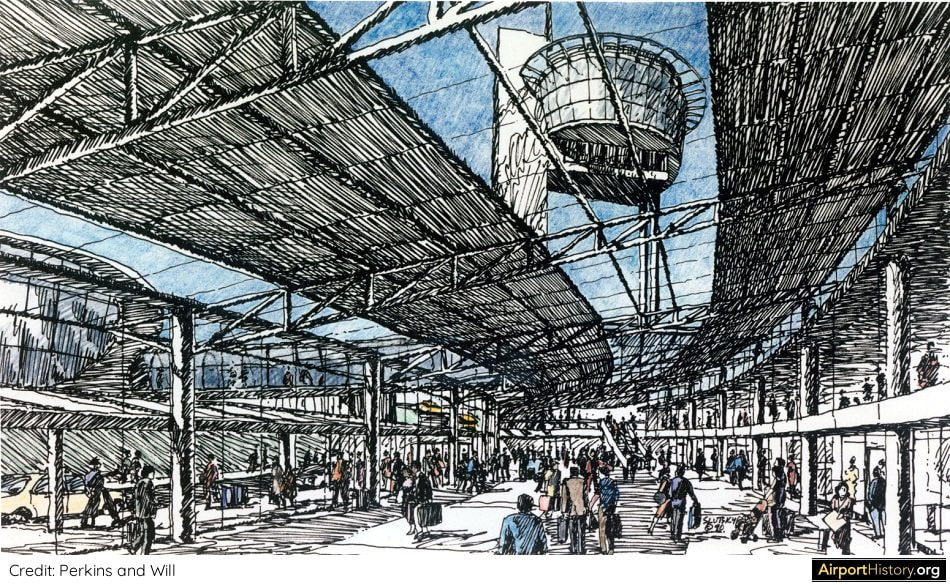

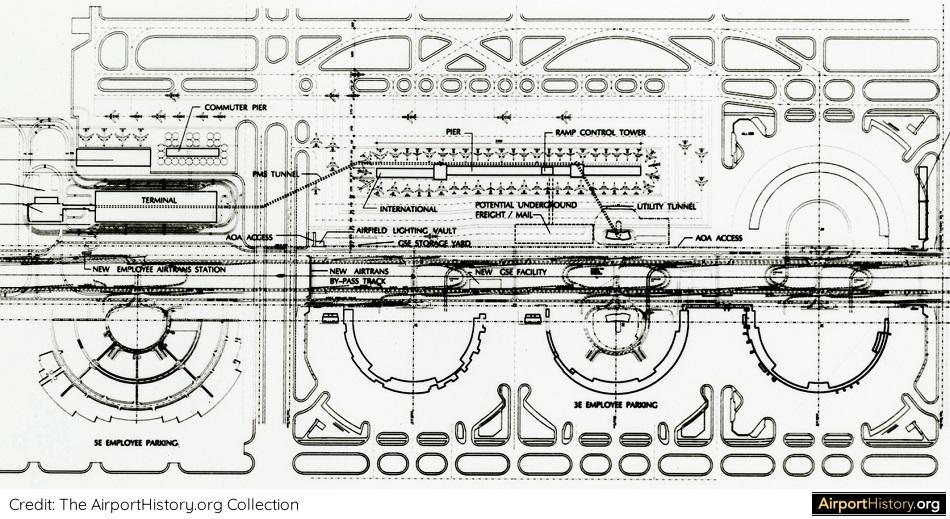

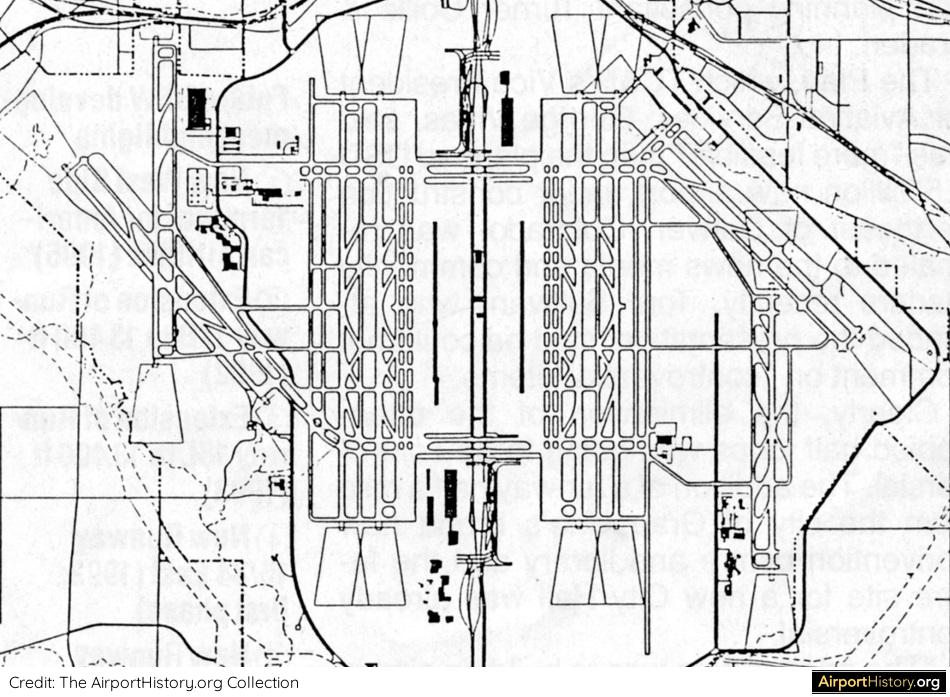

Thankfully, the TWA Flight Center had been able to acquire landmark status and escape the wrecking ball, contrary to other illustrious JFK terminals such as the Pan Am Worldport and the Sundrome, A new Terminal 5, operated by JetBlue, opened on October 22, 2008. The entry hall of the newer Gensler designed terminal wraps around the former terminal in a crescent shape. Although the old satellite buildings, called "Flight Wing One" and "Flight Wing Two", were demolished, the original tube connectors leading passengers from the terminal building, called the "head house", were retained. After standing empty for nearly two decades, the TWA Flight Center found a new life. In May 2019, the TWA Hotel opened to the public. Although commercially the hotel has had a bumpy take-off, it has become a place of pilgrimage for aviation geeks from around the world. However, did you know that back in 1990 a plan was developed to expand the TWA Flight Center? If built, the terminal might still have been with us today as a working terminal, instead of a hotel. A 1990 PLAN FOR A REVAMPED TWA FLIGHT CENTER By the 1980s, the deficiencies of the TWA Flight Center had become very apparent. The terminal had too little of everything: gates, check-in space, baggage handling facilities, curb space, etc. In 1990, Trans World Airlines--at the time still in a relatively healthy state--commissioned Perkins and Will to work on a redevelopment project for its whole JFK complex, which by then included the former National terminal, a.k.a. the Sundrome.

NEW FLIGHT WING TWO

The most radical feature of the proposed scheme was a complete replacement of the original Flight Wing Two satellite building. It would be replaced by a "Y"-shaped 20-gate concourse, with most stands being able to accommodate wide-body aircraft. Having been opened in 1970, Flight Wing One, was still a relatively young structure at the time, and thus was maintained with an extension being added. A new Federal Inspection Services (FIS) facility, "meeters and greeters" hall and arrival roadway would be built in a curved shape around the iconic TWA head house. These were all planned to be depressed below the apron level to preserve the openness and views to the airfield from the head house. Wow!

FLIGHT CENTER BECOMES CHECK-IN FACILITY

The head house itself would be used for check-in. One of the adjoining wings would have been expanded to accommodate more check-in desks for international flights. The famous concrete connector tubes leading from the head house to the flight wings would have been replaced with glassed-in tubes equipped with escalators. Interestingly, in the original design for the Flight Center, the tubes featured escalators and a glass roof. However, the design was simplified in an attempt to contain the cost of the project. CONNECTION BETWEEN TERMINALS The then-existing corridor between the Flight Center and the Sundrome would be replaced with a large connecting structure, containing baggage transfer facilities and an expanded domestic baggage claim area. In between the terminal was a people mover station. The tracks would lead to a newly-built central terminal building, which was part of the shelved JFK 2000 Master Plan (which will be discussed in a later article). See more from the models and renditions of the plan below.

PUBLIC RESPONSE

The plan aroused great public concern and a campaign was launched to protect the Flight Center, which culminated in the Landmarks Preservation Commission granting landmark status for the exterior and some of the interiors on July 19, 1994. In addition, the protection status included Flight Wing Two in its entirety. In the end, the redevelopment did not go ahead as TWA reduced the scale of its operations and retrenched back to the Saarinen building. The rest, as they say, is airport history!

MY TAKE

Even after 30 years, the proposed design for the expansion of the TWA Flight Center still looks pretty nice! It also seemed to be an effective solution as well, providing a huge expansion, while still being very respectful toward the original Flight Center head house--even putting the arrival facilities below grade just to maintain a nice ramp view from the lounge! I was not able to locate any budget estimates but it seemed like it was a costly solution. Even in 1990, TWA was not in a state to afford a project like that. Alas, it did not come to be. As an airport planner and fan, I actually don't like terminals being converted to alternative uses such as shopping malls, entertainment centers or hotels. The best use of an airport terminal is...as an airport terminal. Having said this, the most important thing is the that the Flight Center is still around and I'm happy to have it anyway I can! What are your thoughts on the scheme? Would it have been a better solution? Let us know in the comments below!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Audrey Barsella of Perkins & Will. Without her kind assistance this article would not have been possible.

In the late 1960s, planners considered completely relocating Toronto Pearson Airport's passenger terminals. Find out the story below!

Toronto Pearson Airport's spectacular "Aeroquay 1" was one of the great airport design experiments of the early Jet Age. Opened in 1964, the aeroquay's circular design sought to minimize walking distances between the car and the airplane. Passenger vehicles reached the terminal by means of an underground tunnel, thereby allowing aircraft to circulate freely on the ramp.

A late 1960s aerial view of Aeroquay 1. The core of the terminal featured a seven-level parking structure accommodating 2,400 cars. The top floor was a plane spotter's heaven, which was also one of the main problems of the design. Sightseers caused exit delays from the car park of 2.5 hours and clogged the access tunnels for the airline travelers to the aeroquay.

LIMITATIONS OF THE AEROQUAY CONCEPT

The Aeroquay had a capacity of 3.2 million passengers annually. The airport's master plan envisaged the construction of a total of four aeroquays, which could be built according to passenger demand. However, with traffic at Pearson booming, the concept quickly revealed its limitations. The circular Aeroquay could not be expanded. In addition, the approach roads to the terminal became heavily congested with airport visitors. Hence, in the mid-1960s, the master plan was abandoned and the planners started contemplating a better solution.

GOING INFIELD

With the experience from Aeroquay fresh in mind, this time the planners emphasized full flexibility. They decided to start with a clean slate and build a new passenger terminal complex in between runway 14/32 (now 15L/33R) and the still-to-be-built parallel runway 15R/33L. The proposed plan envisaged a number of linear terminal modules arranged along a central spine road, a popular airport planning concept back then. Additional terminal modules be easily added according to demand, while existing buildings could be enlarged.

Pearson airport layout showing the proposed passenger infield terminal complex. The central location of the terminals enabled aircraft to quickly taxi to and from the surrounding runways. The complex could easily be extended according to demand. The spine road was directly connected to the 401 Freeway.

There were no concourses or satellites. Aircraft would park directly alongside the terminals. Planners did retain one key feature of Aeroquay 1 though, with multi-level parking structures built on top of the terminals.

An artist's impression of the new passenger terminal complex looking west. The complex could be expanded according to demand. The space in between the terminals and central spine road could be used to enlarge the existing structures. Note that airplanes were parked parallel to the terminal (not nose-in), which in the 1960s was still commonplace.

"TEMPORARY" TERMINAL 2

The jump to the infield area was to be made sometime during the 1970s. A "temporary" Terminal 2 would be built to bridge the gap until the first phase of the new terminal complex could be opened. However, the scheme was abandoned due to cost and it was decided to expand within the existing footprint. Phase I of Terminal 2, which adopted a more conventional linear design, opened in 1972, with Air Canada transferring all flights there in June 1973. The building went on to function as the global hub facility of Air Canada for the next three decades.

A small remnant of the infield plan did remain however. In 2002, a passenger satellite terminal called the Infield Terminal (IFT), built to deal with peak demand, opened in the infield area. The rest of the infield area was used for new cargo, maintenance and de-icing facilities.

What are your thoughts about the infield plan? Would it have made sense? Let us know in the comments below!

THIS IS AN OLDER BLOG POST ABOUT THE 1989 PLAN TO REBUILD DFW AIRPORT. PART 1 OF AN BRAND-NEW EXPANDED ARTICLE ON THE PLAN, CAN BE FOUND HERE. In 1989, a spectacular plan was presented that saw the elimination of Dallas/Fort Worth Airport's characteristic semi-circular terminals, replacing them with gigantic linear terminals. Read all about it below! CHANGING REQUIREMENTS With its semi-circular terminal buildings, Dallas/Fort Worth Airport has one of the most recognizable airport layouts in the world. Opened in January, 1974, the airport's "drive-to-the-gate" concept was devised in a time when it was thought that "DFW" would mainly serve people originating in, and destined for the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. Each of the four terminals would serve one major airline or a group of smaller airlines. In the master plan it was envisaged that 13 circular terminals would be built. However, in the years following deregulation in 1978, airlines shifted to the hub-and-spoke model and airports were increasingly dominated by one or two carriers. By 1987, DFW's two principal airlines, American and Delta, carried over 80% of the airport's traffic and they transferred two-thirds of their passengers. For one, this meant that increasingly passengers had to switch between terminals in order to catch their connecting flight. Although the terminals were connected by an automated people mover, it was quite slow and only traveled in one direction! Hubbing also lead to aircraft congestion during peaks, as both airlines operated on the eastern side of the airport. LINEAR CONCOURSES In 1987, planners suggested to build three small "Atlanta-style" concourses west of, and perpendicular to International Parkway, the north-south highway dissecting the airport. By 1989, this had evolved into a scheme to build a single very long concourse, parallel to International Parkway. This new facility would be used exclusively by American Airlines. By 2010, all half-loop terminals would be eliminated, to be replaced with linear terminals both east and west of the International Parkway. The scheme would double the number of gates from over a 100 to 200. Traffic forecasts showed that traffic would rise from 47.5 million passengers in 1989, to over a 100 million passengers and a whopping 1.2 million aircraft movements by 2010, a number that could be comfortably handled by the new layout. At the time, the total project cost was calculated at USD 3.5 billion (USD 7.2 billion in 2019 dollars), only USD 300 million less than the projected cost for the gigantic new Denver Airport, which was being developed at the time in tandem. Due to the huge cost, the scheme was abandoned. Instead, the existing facilities were improved and expanded. As we know now, the traffic never grew to the extent that was forecast back in the late 1980s. Although DFW by all means is a mega-hub, the airport handled only 69.1 million passengers in 2018. Hope you enjoyed!

PART 1 OF A FULL FEATURE ON THE WESTSIDE TERMINAL IS NOW ONLINE. YOU CAN READ IT HERE. PART 2 IS NOW ONLINE! YOU CAN FIND IT HERE. Do you have other interesting information about this plan? Please share it below ↓ |

With a title inspired by the setting of the iconic 70s film "Airport", this blog is the ultimate destination for airport history fans.

Categories

All

About me

Marnix (Max) Groot Founder of AirportHistory.org. Max is an airport development expert and historian. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed